The Dream of Connecting Two Oceans

Picture this: a nation split in half by thousands of miles of untamed wilderness, rugged mountains, and endless plains. Back in the 1850s, getting from New York to California meant either a treacherous six-month journey by wagon train or a dangerous sea voyage around South America. Even nonstop stagecoach service that began in 1858 cost $200 per person—approximately $5,000 in 2023—to cover the 2,800-mile route between St. Louis and San Francisco. The dream of an iron highway spanning the continent seemed almost impossible. Yet visionaries like Asa Whitney, a New York merchant, began pushing for this massive undertaking as early as 1845.

In 1853, U.S. Secretary of War Jefferson Davis commissioned the Pacific Railroad Surveys to “ascertain the most practical and economical route for a railroad from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean.” Under the direction of Brevet Captain George B. McClellan, the U.S Army Corps of Topographical Engineers surveyed potential routes. The idea was gaining momentum, but political divisions would delay the project for years.

War Creates Opportunity

Sometimes the most extraordinary achievements come from desperate times. When the South seceded from the Union at the beginning of the American Civil War, they could no longer lobby for a transcontinental route through the southern United States. This political shift opened the door for northern politicians to finally push through their vision. In 1862, Congress settled on a route between St. Louis, MO, and Sacramento, CA, and passed the Pacific Railroad Act guaranteeing public land grants and loans to the Union Pacific and Central Pacific Railroads to build the transcontinental line.

President Abraham Lincoln signed the Pacific Railroad Act on July 1, 1862, right in the middle of the Civil War. The timing wasn’t coincidental – Lincoln saw the railroad as crucial for keeping the western territories connected to the Union. On July 1, 1862, well into the second year of the Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln signed the Pacific Railroad Act of 1862. While amid a country divided, the Pacific Railroad Act of 1862 opened the idea of a railroad that ran from the Missouri River to the Pacific Ocean.

The Great Railroad Race Begins

The Pacific Railroad Act set up what would become one of the most intense construction races in American history. Under the Act, the Union government chartered the Central Pacific and Union Pacific Railroad companies to construct this colossal rail line. The Central Pacific Railroad Company started construction of the Transcontinental Railroad in Sacramento, California, while the Union Pacific Railroad Company started near the Iowa-Nebraska border. Both companies were promised vast amounts of land and government bonds for each mile of track laid down on the railroad.

Thus started a competition between the two companies to see who could lay as much railroad track down as possible. The first rails were spiked in January of 1863. However, the real construction wouldn’t begin until after the war ended. However, the bulk of the construction of the Transcontinental Railroad would not truly start until after the end of the Civil War.

Government Backing and Financial Incentives

The federal government didn’t just give moral support – they put serious money behind this project. For track laid down on level land, the federal government promised each company $16,000 per mile, or about $461,000 today. And lastly, the federal government would pay each company $48,000 for each mile of track laid in mountains, or about $1,383,000 today. That’s real money, even by today’s standards.

The land grants were equally massive. Congress granted the railroad companies 6,400 acres of government-owned lands for every ten miles of track laid to help create maintenance yards and sidings. The amount of land that the two companies received from the federal government equated to about the size of Texas. Between state and federal government land grants, the two companies owned about 180,000,000 acres of land by the end of construction.

The Central Pacific’s Mountain Challenge

While the Union Pacific had relatively flat prairie to work with, the Central Pacific faced a nightmare scenario. The Central Pacific Railroad Company moved slowly through the Sierra Nevada Mountains. The company suffered tremendously with worker retention due to how brutal the labor was. The granite peaks of the Sierra Nevada seemed almost impossible to conquer with 1860s technology.

Another mantle that the Central Pacific Railroad Company faced was getting through the Sierra Nevada’s. To get through the Sierra Nevada’s, the Central Pacific built massive trestle bridges and blasted through the mountains with gunpowder and nitroglycerine. The work was so dangerous that experienced miners refused to take the jobs, forcing the company to look elsewhere for workers.

The Chinese Workers Who Built the West

When white workers wouldn’t tackle the deadly mountain work, Central Pacific made a decision that would change American history. Charles Crocker of the Central Pacific decided to hire Chinese laborers, approximately 50,000, to work on the Transcontinental Railroad. The Chinese laborers proved to the Central Pacific that they were tireless workers. And even though they made major contributions to the construction of the Transcontinental Railroad, these 15,000 to 20,000 Chinese immigrants have been largely ignored by history.

At the height of the construction, 80-90% of the railroad workforce was Chinese. Chinese workers, though compensated for their work, were still paid about $10-15 less than their White counterparts. Working conditions were incredibly dangerous and workers were offered no protections. It is estimated that about 1 in 10 Chinese laborers working on the Sierra Nevada leg of the transcontinental railroad died from inter-racial violence, rockslides, explosions, environmental exposure, violence and even avalanches.

Dangerous Work and Deadly Conditions

The statistics tell a grim story about the human cost of this engineering marvel. The Central Pacific did not keep records of the deaths of any workers on the railroad, but a great many men were lost during construction – and most of those workers were Chinese. Some historians estimate from engineering reports, newspaper articles and other sources that between 50 to 150 lives were lost as a result of snow slides, landslides, explosions, falls and other accidents, as well as sickness; other estimates run to 2000 or more Chinese dead.

The work at places like Cape Horn was especially treacherous. In the summer of 1865 the railroad builders faced one of their biggest challenges, a roadbed curving around a mountain high in the Sierra Nevada, named Cape Horn (Mile 57/Kilometer 91.7) after the treacherous route for ships sailing around the tip of South America. Workers had to be lowered in baskets to chip away at solid granite with hand tools and explosives.

The Union Pacific’s Prairie Sprint

Meanwhile, the Union Pacific had its own challenges racing across the Great Plains. During the winter of 1865–66, former Union General John S. Casement, the new Chief Engineer, assembled men and supplies to push the railroad rapidly west. To protect the railroad’s surveying and hunting parties, the U.S. Army instituted active cavalry patrols that grew larger as the Indians grew more aggressive.

Temporary, “Hell on wheels” towns, made mostly of canvas tents, accompanied the railroad as construction headed west. The railroad bridged the North Platte River over a 2,600-foot-long (790 m) bridge at North Platte, Nebraska, in December 1866 after completing about 240 miles (390 km) of track that year. These mobile towns were notorious for gambling, drinking, and violence.

The Final Push and Golden Spike

By early 1869, the two railroad companies were racing toward each other with incredible speed. In the final year of construction, Central Pacific crews lay approximately 560 miles of track between Reno, NV, and Promontory Summit, UT, including a single-day record of more than 10 miles of track on April 28, 1869. The competition had become so fierce that both companies were building shoddy sections just to claim more government money.

In early 1869, the two companies were within four miles from one another. Newly elected President and former Civil War General Ulysses S. Grant explained to the two companies that the federal government would withhold funding if they could not come up with a meeting point. Hastily, the two companies decided that they would meet at Promontory Summit, just north of the Great Salt Lake in Utah.

The Moment That Changed America

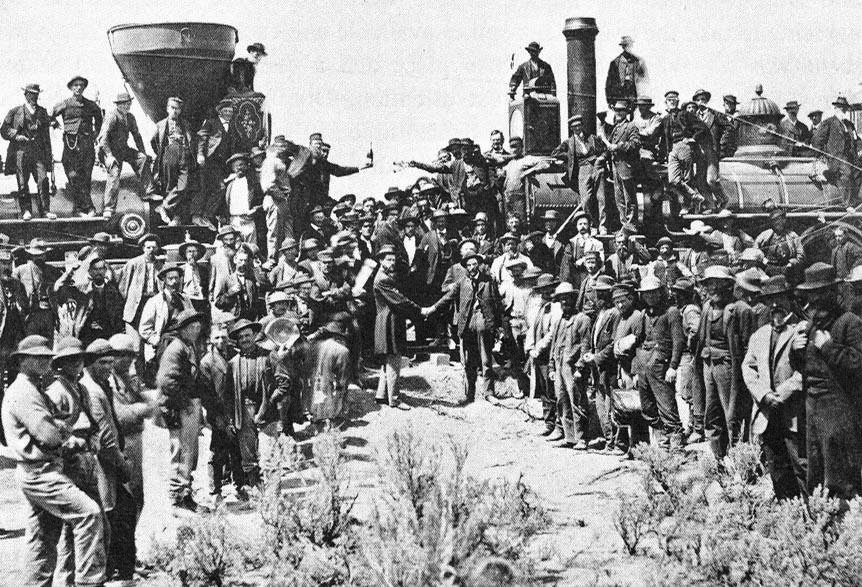

On May 10, 1869, Central Pacific Railroad President Leland Stanford used a silver hammer to drive a ceremonial golden rail spike that completed the 1,912-mile-long Central Pacific and Union Pacific Railroads’ tracks at Promontory Summit, UT. The ceremony marked the opening of the United States’ first transcontinental railroad. On May 10, 1869, at 12:47 p.m., the final spike was driven into the last bit of track. Called the “Golden Spike Ceremony”, the last spike linked the two railroads to create a transcontinental railroad.

The 6-year construction project opened huge swaths of the United States to settlement and reduced the average travel time between New York City, NY, and San Francisco, CA, from months in 1860 to just 7 days by 1870. The transformation was immediate and dramatic. Before the building of the Transcontinental Railroad, it cost nearly $1,000 dollars to travel across the country. After the railroad was completed, the price dropped to $150 dollars.

The True Cost of Progress

The financial numbers are staggering when you put them in perspective. The UPRR main line was completed in 1869, at a cost of $109 million ($2.57 billion in 2024). About $50 million was spent on the construction work. That’s equivalent to over two and a half billion dollars in today’s money – a massive investment for a country still recovering from civil war.

But the railroad’s impact on America’s economy was immediate and transformative. Railroads may no longer be the fastest way for passengers to cross the United States, but they continue to play an indispensable role in our nation’s economy. In March 2023, the Bureau of Labor Statistics estimated that the nation’s railroads employed approximately 149,400 people. These employees of the nation’s seven Class I railroads (railroads with operating revenues of $490 million or more), 22 regional, and hundreds of local/short line railroads move around 1.7 billion tons of freight over 140,000 miles of track annually, according to the Association of American Railroads.

A Legacy Written in Iron and Blood

The Transcontinental Railroad stands as one of the greatest engineering achievements in American history, but its story is complex and often tragic. Efforts to depict the transcontinental railroad as a grand project created by and for white Americans began just moments after the railroad was completed in 1869, when a symbolic Golden Spike was hammered into the ground in Promontory Summit, Utah, where the rails constructed by the Central Pacific and Union Pacific met. Although the majority of railroad laborers came from China, they were left out of the formal documentation of the ceremony marking the project’s completion.

The official photo shows two engineers shaking hands, surrounded by workers with champagne bottles. Not one of the workers visible in the picture was Chinese. This erasure of the Chinese contribution would continue for over a century, only recently being corrected by historians and activists working to tell the complete story of who really built America’s first transcontinental railroad.

The iron highway that connected America from sea to shining sea wasn’t just built with steel and steam – it was forged with the sweat, blood, and sacrifice of thousands of workers, many of whom remain nameless in the history books. Yet their legacy lives on in every mile of track that still carries freight across the continent today.