Alexander McGillivray: The Creek Diplomat Who Set Presidential Precedent

Alexander McGillivray, a mixed-race Creek chief who spoke fluent English, emerged as one of the most influential Native American leaders in early U.S. policy formation when twenty-eight Creek chiefs led by McGillivray accepted George Washington’s invitation to travel to New York in the summer of 1790 to negotiate a new treaty. This meeting marked the first time a sitting U.S. president personally engaged in such extensive negotiations with tribal leaders. The result was the Treaty of New York which restored to the Creeks some of the lands ceded in the treaties with Georgia, and provided generous annuities for the rest of the land. McGillivray’s bilingual abilities and political acumen allowed him to navigate both worlds effectively, establishing a template for future diplomatic relations between sovereign nations.

Near the beginning of his first term as President, George Washington declared that Native American policy was one of his highest priorities. McGillivray’s influence on this early policy framework cannot be overstated – his negotiations directly shaped how the federal government would approach tribal relations for decades to come.

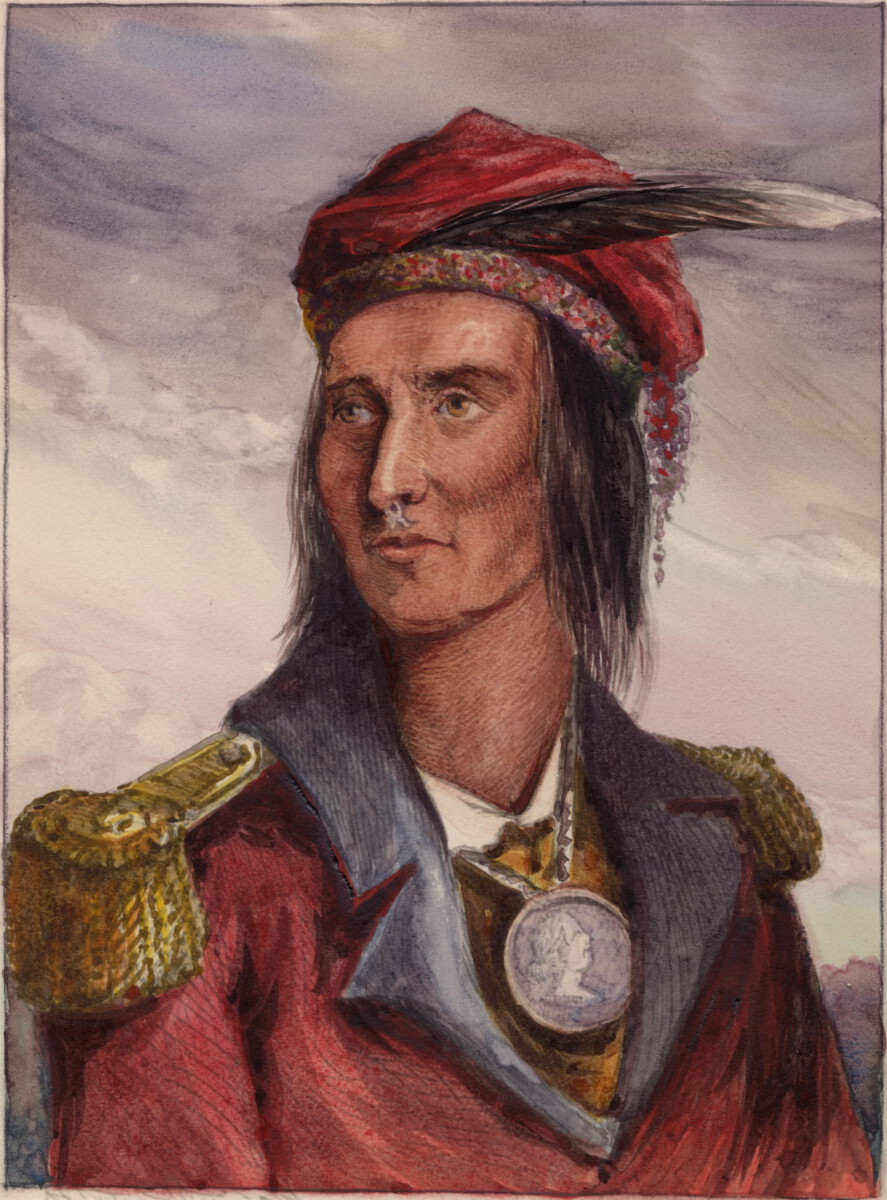

Tecumseh: The Visionary Who Challenged Land Ownership Concepts

Tecumseh was a Shawnee warrior chief who organized a Native American confederacy in an effort to create an autonomous Indian state and stop white settlement in the Northwest Territory, firmly believing that all Indian tribes must settle their differences and unite to retain their lands, culture and freedom. Tecumseh was a man who said, ‘We have to come together and stand together. If we don’t, they’re going to pick us off bit by bit by bit,’ advocating that ‘land ownership is a Native American phenomenon, not a tribal phenomenon. It’s not Shawnee land, it’s not Cherokee land, it’s not Creek land, it’s not Delaware land. We all own it. Together.’

A major turning point came in September 1809, when William Henry Harrison, governor of the Indiana Territory, negotiated the Treaty of Fort Wayne, purchasing 2.5 to 3 million acres of land in what is present-day Indiana and Illinois, and according to historian John Sugden, this “put Tecumseh on the road to war” with the United States. Tecumseh insisted that the Fort Wayne treaty was illegitimate, asked Harrison to nullify it and warned that Americans should not attempt to settle the lands sold in the treaty.

Red Cloud: The Strategic Warrior Who Forced Government Concessions

Red Cloud was one of the most capable Native American opponents whom the United States Army faced in the western territories, leading the Lakota to victory over the United States during Red Cloud’s War, establishing the Lakota as the only nation to defeat the United States on American soil. The Fetterman battle dramatized the failure of the army’s Indian policy and gave new impetus to calls for negotiating peace with the Sioux — particularly with Red Cloud, who refused to negotiate until the army abandoned the forts along the Bozeman Trail, and his strategy was so successful that by 1868, the U.S. Government agreed to draft the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868.

His trip to Washington, DC, had convinced him of the number and power of European Americans, and he believed the Oglala had to seek peace. Red Cloud’s diplomatic approach after military success demonstrated how Native leaders could leverage battlefield victories into policy negotiations, fundamentally changing how the U.S. government approached treaty-making with powerful tribal confederations.

Crazy Horse: The Military Strategist Who Redefined Warfare Tactics

Crazy Horse’s tactical and leadership role in the Battle of the Little Bighorn remains historically significant, while some historians think that Crazy Horse led a flanking assault ensuring the death of Custer and his men, with his personal courage attested to by several eye-witness Indian accounts. Water Man, one of only five Arapaho warriors who fought, said Crazy Horse “was the bravest man I ever saw. He rode closest to the soldiers, yelling to his warriors. All the soldiers were shooting at him, but he was never hit,” while Sioux battle participant Little Soldier said, “The greatest fighter in the whole battle was Crazy Horse.”

His innovative guerrilla tactics and refusal to be confined to reservations forced the U.S. military to completely rethink their approach to warfare on the Great Plains. The psychological impact of Crazy Horse’s victories influenced policy discussions about the feasibility of military solutions versus diplomatic negotiations with resistant tribes.

The Shawnee Prophet: Religious Leader Who Influenced Cultural Policy

In 1805, Tecumseh’s younger brother Tenskwatawa, who came to be known as the Shawnee Prophet, founded a religious movement that called upon Native Americans to reject European influences and return to a more traditional lifestyle, with the Prophet’s message spreading widely, attracting visitors and converts from multiple tribes. The witch-hunts inspired a nativist religious revival led by Tecumseh’s brother Tenskwatawa (“The Prophet”) who emerged in 1805 as a leader among the witch hunters, attracting a large number of followers, mostly Shawnee but some of his early followers were also Wyandot, Mingo, and Odawa.

The Prophet’s religious movement directly challenged U.S. assimilation policies by promoting traditional Indigenous values over American cultural practices. This spiritual resistance influenced government policies regarding religious freedom and cultural preservation in later treaty negotiations, setting precedents for how religious leaders could shape political discourse.

Little Turtle: The Diplomatic Warrior Who Balanced Resistance and Cooperation

As the war chiefs, like Little Turtle, were removed from power following the war, that large confederacy of villages in the region began to fade and the civil chiefs urged their people to work with the United States in order to maintain peace. Little Turtle’s transformation from successful military leader to advocate for peaceful coexistence demonstrated an alternative approach to U.S.-Indigenous relations. His strategic shift from warfare to diplomacy influenced policy makers who saw cooperation as more sustainable than constant conflict.

Little Turtle’s ability to navigate both military resistance and peaceful negotiation provided a model for how Indigenous leaders could maintain dignity while adapting to changing circumstances. His approach influenced federal policies that distinguished between “hostile” and “friendly” tribes, creating different pathways for engagement.

Black Hoof: The Accommodationist Chief Who Shaped Assimilation Policies

The brothers hoped to reunite the scattered Shawnees at Greenville, but they were opposed by Black Hoof, a Mekoche chief regarded by Americans as the “principal chief” of the Shawnees, and Black Hoof and other leaders around the Shawnee town of Wapakoneta urged Shawnees to accommodate the United States by adopting some American customs, with the goal of creating a Shawnee homeland with secure borders in northern Ohio.

Black Hoof’s accommodationist approach provided the U.S. government with a successful model for peaceful assimilation policies. His willingness to adopt certain American practices while maintaining Shawnee identity influenced later federal policies that sought to “civilize” Native Americans through education and agricultural programs rather than through force alone.

Shing-Gaa-Ba-W’OSin: The Eloquent Opponent of Land Cessions

The Chippewa chief Shing-Gaa-Ba-W’OSin (Figured Stone) eloquently exemplified this position of those who steadfastly opposed giving land to the Euro-Americans, and at the treaty negotiations at Fond du Lac, Shing-Gaa-Ba-W’OSin, who had repeatedly suggested that he would resist White settlement, rejected efforts on the part of the federal negotiators to change his position.

His articulate resistance speeches became models for how Indigenous leaders could use diplomatic forums to express opposition to U.S. expansion. The speeches of tribal leaders at several treaty proceedings during the 1820s made obvious the collapse of the pan-Indian alliance masterminded by Tecumseh, in particular, response to the federal government’s unending request for land, whether directly stated or indirectly achieved, varied dramatically. His eloquence demonstrated that Native Americans were sophisticated political actors capable of complex negotiations.

Contemporary Native Voices in Modern Policy Formation

Co-chaired by the Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland and White House Domestic Policy Advisor Neera Tanden, WHCNAA membership consists of heads of federal Departments, Agencies, and Offices, with an Executive Director and inter-agency staff carrying forward WHCNAA priorities grounded in the trust responsibility and treaty rights and informed by consistent and substantive engagement with Tribal Nations. Democrats have been inspired by members of their parties in higher roles, often pointing to Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, the first Native person in a Cabinet post, and heading a department that had been known for its abuse of tribes.

Between 1993 and 2023, there has been a 300% increase, to about 80, in the number of state legislators alone who self-identify as Native American. This dramatic increase reflects how historical Native voices paved the way for contemporary Indigenous political participation.

Electoral Influence and Political Representation Patterns

Native American voters leaned Democratic in the 2024 elections, with 57% supporting Harris compared to 39% for Trump, while prioritizing tribal sovereignty, land rights, and cultural preservation as key voting issues. At least 170 Native American, Native Hawaiians, and Native Alaskans are on ballots this fall, an all-time high, with at least 246 candidates, including 140 incumbents, running for office in 25 states this year.

The Harris-Waltz campaign invested heavily in outreach, launching a $370 million ad campaign between Labor Day and Election Day that focused on key Native issues such as treaty rights and tribal sovereignty, with the campaign prioritizing direct engagement, including meetings with tribal leaders and rallies held in Arizona’s Gila River Indian Community. This level of political engagement traces back to the diplomatic traditions established by early Native leaders who understood the importance of direct negotiation with federal officials.

Economic Policy Influence and Tribal Sovereignty Recognition

With tools like the Buy Indian Act, the Department has had an outsized impact on improving the funding that Tribes and Native business leaders receive, with this past year alone, Interior awarding over 1.4 billion in contracts to Indian-owned and controlled businesses – up from just 317 million in Fiscal Year 2019. Over the next seven years, the Vision Partnership will raise and deploy 1.2 billion dollars in impact for Tribal communities – a historic effort that will support priorities like community development, new clean energy opportunities, and support for Native small businesses.

These modern economic policies build directly on the sovereignty principles established by early Native leaders who insisted on nation-to-nation relationships. The dramatic increase in federal contracting with Native businesses reflects the long-term success of tribal leaders who fought to maintain economic independence.

Legal Precedents and Supreme Court Influence

Tribal leaders formed the Tribal Supreme Court Project in 2001 and had the Native American Rights Fund and the National Congress of American Indians staff it, with the project monitoring all of the cases that are headed to the Supreme Court and offering assistance in whatever way that it can, and the project has a workgroup of about 300 Tribal attorneys, Indian law professors, and Supreme Court practitioners who participate.

President Richard Nixon announced the new federal Indian policy of Indian self-determination and recognition of Tribal sovereignty in 1970, changing the old policy of termination of tribes and forcing the assimilation of Indians into mainstream society. This policy shift represented the culmination of centuries of Native American advocacy that began with leaders like McGillivray and Tecumseh who insisted on treating with the United States as sovereign equals rather than subordinates.

Education and Cultural Preservation Impact

Over the past three years, this Initiative has shed light on this horrific era of our nation’s history, leading to a two-part investigative report which found that the federal government took deliberate and strategic actions through boarding school policies to isolate children from their families and steal from them the languages, cultures, and traditions that are foundational to Native people, and it created The Road to Healing, a 12-community journey giving survivors and descendants opportunities to share their boarding school experiences.

This contemporary acknowledgment of historical injustices builds on the cultural preservation efforts that leaders like the Shawnee Prophet initiated centuries earlier. The federal government’s current approach to cultural restoration reflects the enduring influence of Native voices who consistently argued for the preservation of Indigenous languages, religions, and traditional practices despite overwhelming pressure to assimilate.

The legacy of early Native American leaders continues to resonate through contemporary policy debates, electoral participation, and federal recognition of tribal sovereignty. From McGillivray’s diplomatic precedents to Tecumseh’s pan-Indian vision, these voices established frameworks that modern Indigenous leaders still use to advocate for their peoples’ rights and interests in an ever-evolving political landscape.