The State of Franklin

When North Carolina ceded its western territories to Congress in 1784 to help pay Revolutionary War debts, something extraordinary happened that almost changed American history forever. Franklin was created in 1784 from part of the territory west of the Appalachian Mountains that had been offered by North Carolina as a cession to Congress to help pay off debts related to the American War for Independence, and in 1784 the state voted to give the land to the U.S. Congress to pay off their war debts. Four counties in what is now eastern Tennessee seized the moment and declared independence as the state of Franklin.

On August 23, 1784, four counties in western North Carolina declare their independence as the state of Franklin, and on August 23, 1784, roughly 50 frontiersmen signed a document in the city of Jonesborough declaring their independence from North Carolina. It was founded with the intent of becoming the 14th state of the new United States. The charismatic Revolutionary War hero John Sevier, for whom Sevierville is named, became governor of this ambitious territory that existed for nearly five years.

The Republic of Texas

Perhaps the most successful of all forgotten potential states was Texas, which managed something no other territory achieved – becoming an actual independent nation for nearly a decade. The Republic of Texas (Spanish: República de Tejas), or simply Texas, was a country in North America that existed for close to 10 years, from March 2, 1836, to February 19, 1846. Texas declared its independence from Mexico in 1836 after the famous battles at the Alamo and San Jacinto, creating a sovereign nation that issued its own currency and maintained diplomatic relations with world powers.

During the Texas Revolution, a convention of American Texans meets at Washington‑on‑the‑Brazos and declares the independence of Texas from Mexico. By April 21, 1836, Houston’s army defeated the Mexicans and captured Santa Anna at San Jacinto, and on May 14, the Mexican leader signed the Treaty of Velasco and withdrew his troops south of the Rio Grande. For nearly ten years, Texas operated as a fully functioning republic with Sam Houston as its first president before finally joining the United States as the 28th state in 1845.

Transylvania – Daniel Boone’s Dream

If he’d had his way, Kentucky would have been called Transylvania and we’d be placing bets on horses at the Transylvania Derby, as Boone hoped to call the colony’s capital Boonesborough, but much to the explorer’s chagrin, North Carolina and Virginia voted against Transylvania’s existence. Daniel Boone, the legendary frontiersman, had grand visions for a state he called Transylvania in the 1770s. Unfortunately for them, the plan unraveled when it was discovered that the purchase was illegal under British law and that the lands had already been claimed by Virginia and North Carolina, as for less than a year, the land existed as an extralegal colony, and shortly before the formation of the U.S., Virginia declared the Transylvania Purchase void and officially reclaimed the lands.

It was made up mostly of modern-day Kentucky and a small portion of northern Tennessee, as Daniel Boone bought the land from the Cherokee Indians in hopes that they would be allowed to govern it on their own, however, the colony of Virginia claimed the same land—and the Continental Congress wasn’t in support of this new state and failed to recognize Transylvania. The dream of Transylvania lasted only about a year before being absorbed back into existing territories.

Deseret – The Mormon State

Deseret is a word in the Book of Mormon word meaning “honeybee,” and when Mormons moved to the southwestern United States and claimed an autonomous region in which to govern themselves, they called it Deseret, with their proposed state taking all of modern-day Utah and parts of several other states, but their statehood request was denied by Congress in 1849, and they were given the much smaller Utah Territory instead. The Mormon settlers had ambitious plans for their territory that would have stretched from the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific Ocean.

Mormons proposed the state in hopes of being able to govern themselves, however there was anti-Mormon bias in the culture at the time, and Congress wasn’t a fan of the new religion either, and also, slave states in the South were opposed to the creation of a new free state in the West. What makes Deseret particularly fascinating is its sheer size – if approved, it would have been one of the largest states in the union, encompassing not just Utah but significant portions of Nevada, California, Arizona, and other western territories.

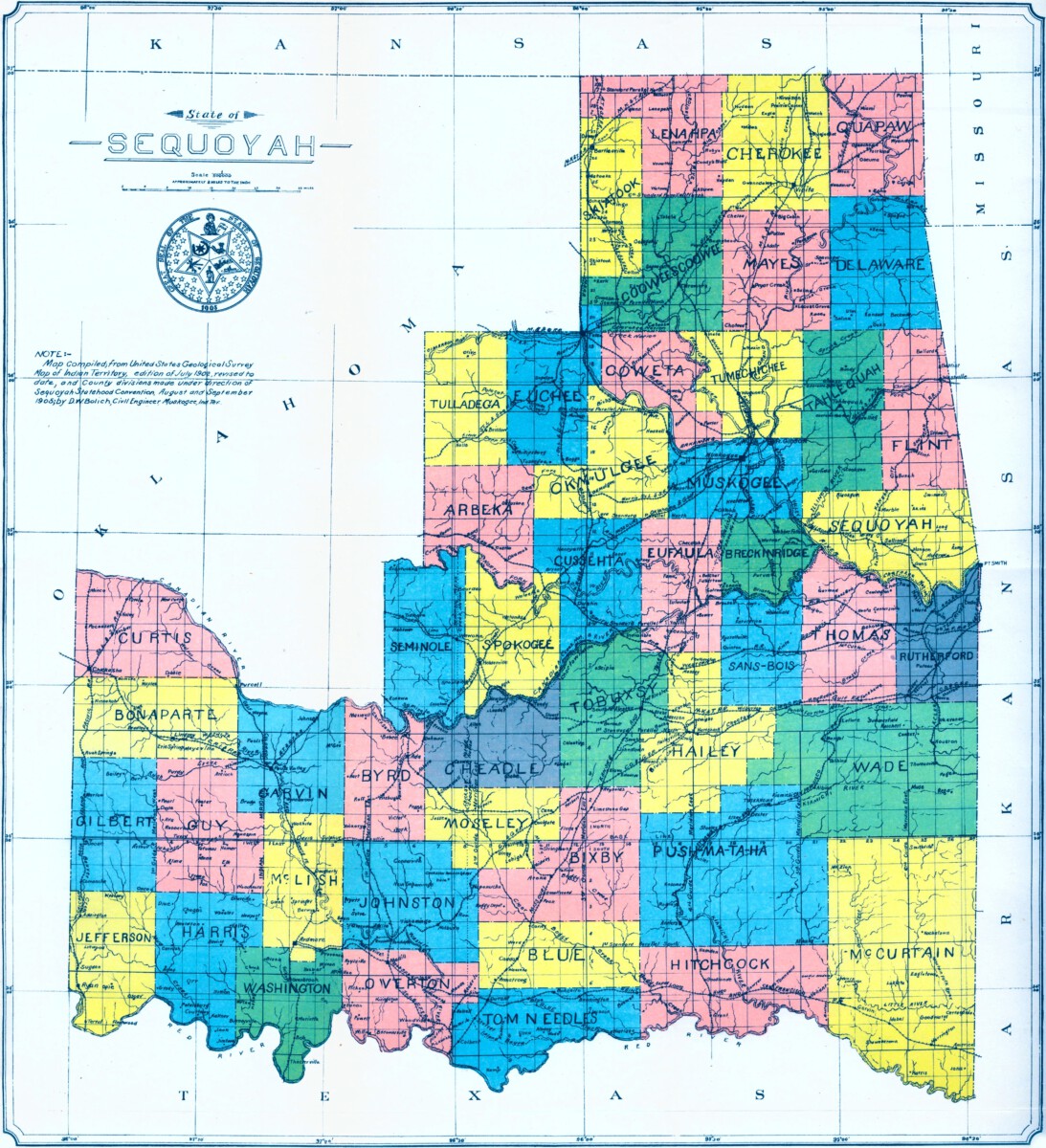

Sequoyah – The Native American State

In 1905, the Five Civilized Tribes—the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Muscogee (Creek), and Seminole—proposed the State of Sequoyah, named for the scholar who invented the Cherokee syllabary, and Sequoyah would encompass the southern and eastern half of present-day Oklahoma, then called Indian Territory, where the five tribes had been forcibly removed by the U.S. government. This remarkable proposal represented one of the most organized attempts by Native Americans to create their own state within the United States system.

Tribal delegates presented the constitution and plans for statehood to Congress, but legislators in Washington were hesitant to support the plans; the members wanted keep the number of states in the eastern and western U.S. balanced, and in the end, President Theodore Roosevelt decided that the Sequoyah proposal should be merged with the existing Oklahoma statehood proposal, creating the current state. But, at the time, Congress and the White House were controlled by Republicans who weren’t in favor of Native Americans having their own state, and Congress refused to consider the proposal and it didn’t become a state—instead, President Roosevelt merged the proposed state of Sequoyah with the existing proposal for the state of Oklahoma.

The Free State of Scott

The Free and Independent State of Scott was founded during the Civil War when Scott County, Tennessee, opted to secede from its parent state after Tennessee joined the Confederate States of America, as citizens of Scott, who weren’t plantation holders or enslavers, had no interest in joining the CSA and so remained a Union state, and Tennessee ignored the proclamation and did nothing to stop them, so the tiny State of Scott was mostly forgotten until its 125th anniversary, when it finally formally requested re-admittance to Tennessee. This miniature state existed for an astounding 125 years, though it was never officially recognized.

The state of Scott was founded during the Civil War, and when Tennessee became a Confederate state, Scott County seceded in order to support the Union, with Tennessee not doing anything to stop them and just forgetting about Scott until its 125th birthday in 1986, when Scott requested readmission—even though the state was never recognized as independent by the government—and a party was held to welcome it back as a part of Tennessee. The fact that this tiny “state” existed for over a century without anyone officially recognizing or dissolving it makes it one of the strangest political entities in American history.

Forgottonia – The Forgotten State

Comprising 14 counties in western Illinois, Forgottonia was an idea created by a group of disgruntled citizens who felt, well, forgotten, and in the early 1970s, the would-be state’s residents proposed an interstate that would run from Chicago to Kansas City, but they were rebuffed and so decided to try to split off. The name itself perfectly captured the sentiment of residents who felt ignored by state government in Springfield. This wasn’t some historical footnote from the 1800s – Forgottonia was a serious proposal from the 1970s that gained surprising traction.

The movement began when residents of western Illinois felt their region was being neglected in favor of the Chicago metropolitan area and other parts of the state. Their proposed interstate highway would have provided much-needed economic development to the region, but when state officials repeatedly rejected their infrastructure proposals, local leaders began seriously discussing secession. The movement eventually faded as political attention and some infrastructure investments were directed toward the region.

Westsylvania – The Revolutionary War State

One of the proposed states that didn’t make the final 50 was the state of Westsylvania, with the idea coming up in 1776 during the American Revolution, and the state would have been created from parts of modern-day Pennsylvania, West Virginia, and Kentucky, but unfortunately for all of the hopeful Westylvanians, their bid was ignored by Congress and never went up for a vote, as Congress chose to ignore the bid because they didn’t want to raise tensions between Pennsylvania and Virginia during the Revolutionary War when it was vital that the country remained united against Great Britain. This strategic oversight during the Revolutionary War illustrates how political timing can doom even reasonable proposals.

The settlers in this region faced unique challenges, being far from established colonial governments and needing local administration to manage their affairs. However, the Continental Congress’s focus on winning the war against Britain meant that potentially divisive internal boundary disputes had to wait. By the time the war ended, the political momentum for Westsylvania had dissipated, and the lands were absorbed into existing states.

Absaroka – The Depression Era State

Anticipation and excitement surrounded every potential new state, and in 1939 the residents of what could have become Absaroka got as far as holding beauty pageants and creating license plates, but due in part to the distraction of the Second World War, they didn’t actually get as far as making a proposal to Congress, and these areas of Wyoming, Montana and South Dakota ended up staying put. This Depression-era movement represented one of the last serious attempts to create a new state in the American West.

What makes Absaroka particularly interesting is how far the movement progressed before World War II changed national priorities. Unlike many other failed state movements that remained purely theoretical, Absaroka residents actually created the infrastructure of statehood – they had license plates printed, held beauty contests to crown Miss Absaroka, and established a functioning promotional apparatus. The name itself came from the Crow tribe’s word for their homeland, showing an unusual acknowledgment of Native American heritage for a proposed 20th-century state.

The Kingdom of Callaway

In October 1861, a lawyer named Col. Jefferson Jones popped up as commander of a little ragtag pro-Confederate band of old men and young boys, and Jones got wind Union General John Henderson was approaching with 600 militiamen, so in a bluff that would have made a poker player proud, Jones marched his little group toward the Federals, parading them in a loop to seem larger than they were, and he hauled out several “Quaker guns,” logs stripped of bark and painted black to look like cannons from afar, and pointed them at the Yankees, then Jones offered Henderson a deal, and if Henderson promised to not occupy the county (which Jones grandly called the Kingdom of Callaway), Jones would disperse his “superior forces” and go home. This Civil War-era “kingdom” in Missouri existed through one of the most audacious bluffs in American military history.

Each briefly existed–more or less–during the Civil War, and it’s worth revisiting their strange stories, as today, the Civil War is viewed as a struggle between neatly aligned Northern and Southern states. The Kingdom of Callaway shows how local politics during the Civil War were far more complicated than the simple North versus South narrative suggests, with individual counties sometimes charting their own course through the conflict.

The Free State of Winston

When that state’s secession convention was called in 1861, it didn’t sit well with Winston County folks, so they held their own convention on July 4, 1861, at Looney’s Tavern (I’m not making that up), and they passed a resolution declaring they wouldn’t take sides or participate in the war, and that made a pro-Confederate lawyer snidely snort, “Winston County secedes, eh? Well, hooray for the Free State of Winston!” and the locals took a shine to the name. Winston County, Alabama, chose neutrality during the Civil War, creating their own “free state” that rejected both Union and Confederate authority.

The story of Winston County illustrates the complex loyalties that existed in the mountainous regions of the South, where slavery was less common and allegiance to the Confederacy was often weak. These mountain counties often had more in common with each other across state lines than with the plantation regions of their own states. The Free State of Winston existed as a practical reality throughout much of the Civil War, with residents largely governing themselves and avoiding participation in the conflict.

The Republic of West Florida

The Republic of West Florida (1810): This short-lived republic, existing for a mere two and a half months, emerged from the confusing territorial disputes following the Louisiana Purchase, and while ultimately absorbed into the U.S., it highlights the complexities of land claims and power struggles in the early 19th century. This tiny republic existed for just ten weeks in 1810, but its brief existence had lasting consequences for American territorial expansion.

The Republic of West Florida emerged from the chaos following the Louisiana Purchase, when the exact boundaries of American territory remained unclear. Local settlers, frustrated with Spanish colonial rule and uncertain about their political status, declared independence and created their own government. Though short-lived, the republic’s flag – a single white star on a blue field – inspired the design that would later become famous as the “Bonnie Blue Flag” of the Confederacy.

Delmarva – The Peninsula State

Another proposed state was the small peninsula of Delmarva, and it was actually proposed as the unofficial 14th colony. The Delmarva Peninsula, comprising parts of modern-day Delaware, Maryland, and Virginia, represents one of the more geographically logical proposed states that never materialized. The peninsula’s unique position between the Chesapeake Bay and the Atlantic Ocean created a distinct regional identity that persisted long after statehood became impossible.

Had these states been established, you might be a Delmarvan or a Nickajacker instead of a Marylander or Tennessean. The peninsula’s residents shared common economic interests centered on fishing, farming, and maritime trade that were often different from the priorities of their respective state capitals. The geographic isolation created by water boundaries made Delmarva a natural candidate for statehood, yet political realities and the existing structure of colonial governments prevented this logical arrangement from ever becoming reality.

These forgotten states represent paths not taken in American history, each one a reminder that the fifty stars on our flag could have been very different. From Daniel Boone’s Transylvania to the Mormon’s Deseret, from Texas’s successful decade of independence to Franklin’s failed attempt at statehood, these territories show us how fluid and uncertain our national boundaries once were. What if we really did have a state called Forgottonia, or if Native Americans had achieved their dream of Sequoyah? The America we know today is just one possible version of what our nation might have become.