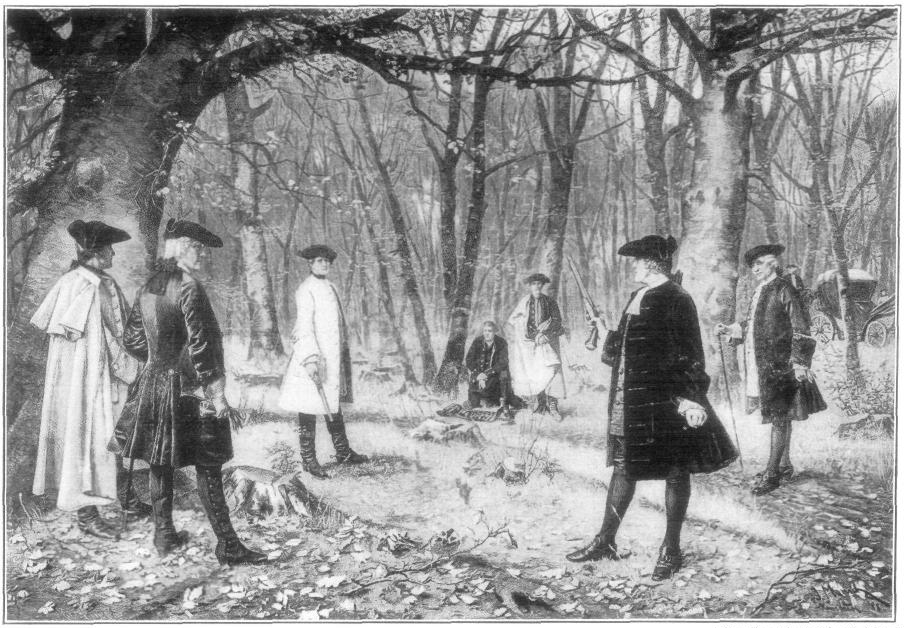

The Fatal Dawn at Weehawken

The Burr–Hamilton duel took place in Weehawken, New Jersey, between Aaron Burr, the third U.S. vice president at the time, and Alexander Hamilton, the first and former Secretary of the Treasury, at dawn on July 11, 1804. Hamilton was transported across the Hudson River for treatment in present-day Greenwich Village in New York City, where he died the following day, on July 12, 1804. What started as a political rivalry became the most consequential duel in American history, forever altering the landscape of early American politics. It is one of the most famous duels in American history. The sight of two prominent political figures facing each other with pistols drawn shocked a nation still figuring out how democracy should work.

The Making of Political Enemies

The men became rivals when Burr ran for the U.S. Senate against Hamilton’s father-in-law, Philip Schuyler in 1791. Burr won the election in the New York state legislature. Burr then became a player in the Democratic-Republican Party in New York, while Hamilton was a top rival Federalist Party leader. This wasn’t just a personal feud – it was a clash between two fundamentally different visions of America. Hamilton was a Federalist. Burr was a Republican. The men clashed repeatedly in the political arena.

“I feel it is my religious duty to keep this man from office,” wrote Hamilton in 1792. In June of 1804, Hamilton referenced a “course of fifteen years competition” between himself and Burr. Indeed, the 15-year long relationship between Hamilton and Burr as colleagues and political rivals is flecked with instances of insults and slights between the two. Their rivalry wasn’t about mere political differences – it was about the soul of the new nation.

Honor Culture Defines Political Life

A man’s reputation was integral to his social standing in early American society, and dueling was a way for him to defend and bolster his name in the public sphere. “Honor was the core of a man’s identity,” explains historian Joanne Freeman in Affairs of Honor. “It did not exist unless bestowed by others.” If a man’s honor was ever challenged, he had to defend himself. In the early republic, honor wasn’t just personal – it was political currency.

But not in court — that was a sign of weakness, writes Temple University law professor Harwell Wells: “For a man to turn to the system to repair his honor, perhaps by filing a libel or slander suit, was akin to a man admitting that he was unable to protect himself.” Honor was particularly important when it came to politics. Without defined political parties, public perception of a candidate’s character and values determined his success. Due to the “gentlemanly standards of behavior” inherent to the ritual of dueling, participating in this practice helped to establish and maintain such a reputation.

The 1804 Gubernatorial Campaign Disaster

The final political confrontation between Burr and Hamilton occurred during the New York gubernatorial election of 1804. Once again there was considerable Federalist sentiment for Burr, but Hamilton supported Republican John Lansing, Jr., who accepted and then declined the nomination. That year, a faction of New York Federalists, who had found their fortunes drastically diminished after the ascendance of Jefferson, sought to enlist the disgruntled Burr into their party and elect him governor. Hamilton campaigned against Burr with great fervor, and Burr lost the Federalist nomination and then, running as an independent for governor, the election.

Although Hamilton’s campaign was probably not the deciding factor, the Burr campaign failed. Burr was crushed in the general election by Morgan Lewis, the Republican candidate, who was supported by George and DeWitt Clinton, powerful New York Republicans. This crushing defeat left Burr’s political career in ruins, with Hamilton’s opposition being the final nail in the coffin.

The Inflammatory Letter That Started Everything

On April 24, 1804, the Albany Register published a letter opposing Burr’s gubernatorial candidacy which was originally sent from Charles D. Cooper to Hamilton’s father-in-law, former senator Philip Schuyler. It made reference to a previous statement by Cooper: “General Hamilton and Judge Kent have declared in substance that they looked upon Mr. Burr to be a dangerous man, and one who ought not be trusted with the reins of government.” Cooper went on to emphasize that he could describe in detail “a still more despicable opinion which General Hamilton has expressed of Mr. Burr” at a political dinner.

The phrase “more despicable opinion” would prove to be the spark that ignited this political powder keg. Burr responded in a letter delivered by William P. Van Ness which pointed particularly to the phrase “more despicable” and demanded “a prompt and unqualified acknowledgment or denial of the use of any expression which would warrant the assertion of Dr. Cooper.” Hamilton’s refusal to clarify or apologize would set the stage for their fatal confrontation.

When Political Honor Demanded Blood

Hamilton wanted to avoid the duel, but politics left him no choice. If he admitted to Burr’s charge, which was substantially true, he would lose his honor. If he refused to duel, the result would be the same. Either way, his political career would be over. Hamilton could have decided not to fight in the duel, but he clearly indicated that he need to preserve his reputation for future use. “The ability to be in future useful, whether in resisting mischief or effecting good, in those crises of public affairs, which seem likely to happen, would probably be inseparable from a conformity with public prejudice in this particular,” Hamilton wrote. In other words, his future reputation would determine his use and role in a future public crisis.

By 1804, dueling had become an American fixture. And for another thirty years or more, its popularity would continue to grow. For politicians especially, refusing a duel was career suicide – even more dangerous than accepting one.

America’s Deadly Political Theater

While duels had long been fought over a woman’s hand, or to defend a man’s honor, in America, dueling took on a new importance: It was used to settle political differences. The duel that took place between Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr is perhaps the most well-known, but it was not uncommon in politics. Freedom of speech and politics were cornerstones of the new country. To besmirch a man because of his beliefs was not taken lightly. Political rivals such as senators, governors, mayors were challenged. Principally duels were held to defend one’s honor, but the duelists were also trying to prove themselves as leaders—brave, determined and single-minded.

Due to the partisan nature of their work, politicians frequently received challenges — as did newspaper editors and attorneys. As a young man, attorney Andrew Jackson, future president of the United States, earned a reputation as a formidable duelist. Politics in early America wasn’t just about votes – it was about proving you had the courage to literally put your life on the line for your beliefs.

The Economic Logic Behind Honor

However, the concept of “defending one’s honor” was not quite as abstract and idealistic as often imagined – losing “honor” often had pecuniary disadvantages that made defending one’s honor a somewhat rational decision, even at risk of being physically harmed or even killed. Dueling to protect one’s credit or honor was partly a response to the underdeveloped credit markets of this region and time period. Given that Southern credit markets were rather opaque until the early 20th century – lenders could not readily view an applicant’s financial statement—having a reputation as “honorable” was almost essential to obtaining approval for loans. In addition, transaction costs were very high during this period; therefore, perceived personal integrity or character was important to being viewed as likely to honor one’s contracts and debts. Thus, the word honor was nearly culturally synonymous with creditworthiness.

Recent research reveals that dueling wasn’t just about masculine pride – it was about economic survival in an era before modern banking and credit systems. The long-term economic penalties for having one’s reputation ruined included limited access to capital and diminished political influence.

The Duel That Destroyed the Federalists

Hamilton’s death permanently weakened the Federalist Party, which was founded by Hamilton in 1789 and was one of the nation’s major two parties at the time. That defeat, the party’s increasing regional isolation and Hamilton’s untimely death at the hands of Aaron Burr that same year threatened the party’s very existence. Hamilton wasn’t just the Federalist Party’s founder – he was its intellectual engine and strategic mastermind.

The death of Hamilton had a major impact on early US politics. He was killed at a time when the Federalist Party was trying to make a comeback after their national defeat in the election of 1800. The Federalists would be unable to find another leader as forceful and energetic as Hamilton had been, and their movement would slowly suffocate before finally petering out in the early 1820s, ending the first round of partisan struggles in US history. One pistol shot essentially ended America’s first political party.

Burr’s Political Suicide

Instead of reviving Burr’s political career, the duel helped to end it. Burr was charged with two counts of murder. After his term as vice president ended, he would never hold elective office again. Although he had hoped to restore his reputation and political career by dueling Hamilton, he effectively ended them. Arrest warrants were issued for Burr, whom many viewed as a murderer, and he fled to Philadelphia, though he was never tried for Hamilton’s death.

Vice President Burr was indicted but not arrested. In 1807, Burr was accused of treason in a separate incident, but he was acquitted in a trial presided over by Chief Justice John Marshall. He quietly worked as a lawyer in New York in his later years. The man who killed Hamilton became a political pariah, proving that even in an honor-based culture, some lines couldn’t be crossed without consequences.

The Decline of Dueling Culture

According to a 2020 study, dueling behavior in the US declined as state capacity (measured by the density of post offices) increased. Dueling in the US virtually disappeared by the start of the 20th century with the rise of modern banking institutions and commercialized lending in the South, which were characterized by greater transparency and lower transaction costs. As America developed stronger institutions, the need for personal honor as a guarantee diminished.

Dueling had lost favor in the early 1800s in the North, but still remained the dispute-solving method of choice in the South, where social standing was a touchier subject. Although 18 states had outlawed dueling by 1859, it was still often practiced in the South and the West. Dueling became less common in the years following the Civil War, with the collective public opinion perhaps soured by the amount of bloodshed during the conflict. By the start of the 20th century, dueling laws were enforced and it became a thing of the past.

The Hamilton-Burr Duel’s Lasting Impact

The Burr-Hamilton duel, a cornerstone of U.S. history, epitomized the intense rivalries shaping early American politics. This single morning in Weehawken changed everything – it ended the life of one of America’s most important founding fathers and destroyed the career of another. More importantly, it marked the beginning of the end for the honor culture that had dominated early American politics.

By the time Alexander Hamilton died on the dueling grounds of Weehawken, New Jersey, the power of the Federalist Party was in terminal decline. The fatal duel between Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr shocked the nation. But it was the identity of the man killed that produced such dismay. The duel didn’t just kill Hamilton – it killed an entire way of doing politics, forcing America to find new ways to resolve political differences without bloodshed.

Democracy’s Violent Growing Pains

The Hamilton-Burr duel represents more than just a personal tragedy – it’s a window into how fragile and violent early American democracy really was. In a nation still figuring out how to transfer power peacefully, dueling offered a deadly alternative to the ballot box for settling disputes. Hamilton’s death marked the end of an era where political disagreements could literally be matters of life and death, pushing America toward the more civilized forms of political combat we recognize today.