The Real Story Behind History’s Greatest Marketing Campaign

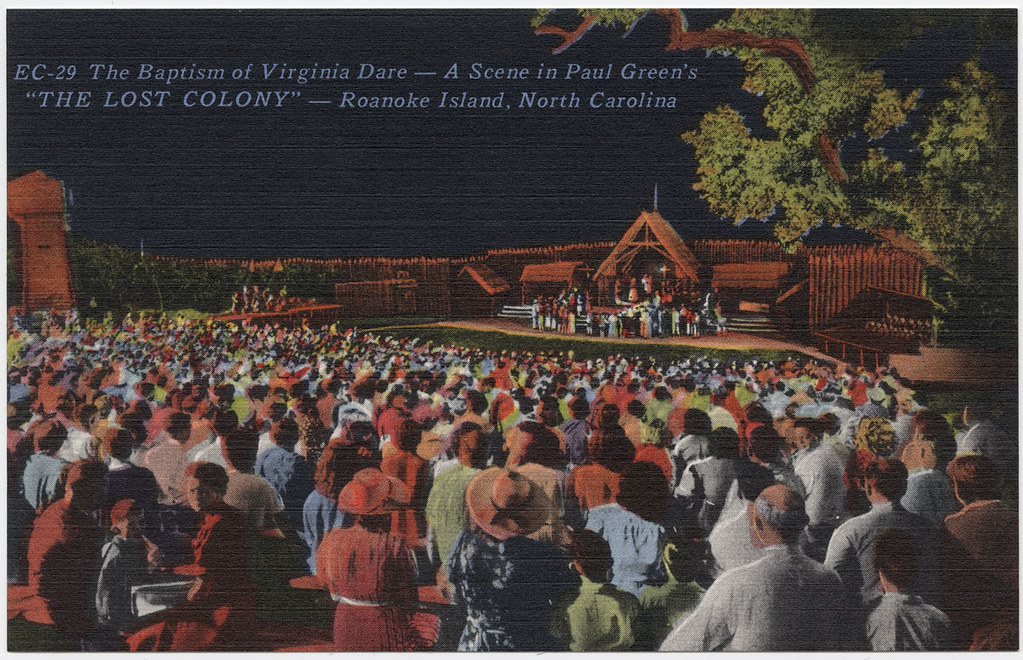

What if one of America’s most enduring mysteries was never really a mystery at all? For over four centuries, the story of the “Lost Colony” of Roanoke has captivated historians, archaeologists, and the general public with its tantalizing disappearance. However, recent archaeological discoveries are rewriting this tale entirely. The Lost Colony is a marketing campaign that started in 1937 and it created this myth of a colony that vanished, according to Scott Dawson, president of the Croatoan Archaeological Society.

The truth emerging from decades of scientific excavation reveals something far more ordinary yet fascinating than the popular narrative suggests. Rather than mysteriously vanishing into thin air, these English settlers made a calculated decision to relocate and integrate with the indigenous Croatoan people on what we now call Hatteras Island. The word “CROATOAN” carved into a tree wasn’t a cryptic message—it was simply the destination.

The Archaeological Evidence That Changes Everything

We’ve been digging there for 10 years off and on, and I think the real breakthrough was the hammer scale mixed in with 16th-century artifacts. Hammer scale is a flaky byproduct of traditional blacksmithing. When iron is heated, a thin layer of iron oxide can form, which is then crushed into small pieces as the blacksmith hammers the iron, explains Mark Horton, archaeology professor at the Royal Agricultural University in the U.K. This discovery represents the smoking gun that archaeologists have been searching for. The presence of hammer scale on Hatteras Island proves that English settlers were living and working there, using metalworking technology that the indigenous population didn’t possess.

Archaeologists found “buckets” of hammer scale, a leftover material from blacksmithing. This is showing a presence of the English working metal and living in the Indian Village for decades. The significance cannot be overstated—this isn’t material that would be traded or randomly left behind. It’s waste from an active blacksmithing operation, indicating permanent settlement and integration.

The Elizabethan Gardens Discovery

Excavations in March 2024 followed discoveries in the summer of 2023, when archaeologists from The First Colony Foundation uncovered what they believe are tantalizing clues. They dug up shards of Algonquian pottery dating back to the 1500s, along with a ring of copper wire they believe could have been an earring once worn by a warrior from an Indigenous tribe. This finding at the Elizabethan Gardens in Manteo reveals the intimate connections between English explorers and the Algonquian village of Roanoke.

The copper ring may indicate contact with the English. Klingelhofer and his colleagues believe the ring was made in England and may have been used in trade. This is because, they argue, the Indigenous peoples at the time lacked the technology to produce the ring’s rounded strands. These discoveries illuminate the trading relationships that existed between the two cultures, setting the stage for eventual integration.

The Hidden Map That Revealed Site X

In a twist worthy of a detective novel, researchers uncovered a new lead in 2012 while examining a map at the British Museum in London that White had painted of the Elizabethan-era United States, titled La Virginea Pars. Hidden in invisible ink, presumably to guard information about the colonies from the Spanish, were the outlines of two forts, one 50 miles west of Roanoke—the same distance away that the colonists had told White they planned to move. This map, painted by colony governor John White himself, contained secrets that remained hidden for over 400 years.

The First Colony Foundation’s team of archaeologists, led by Nick Luccketti, set out to investigate the site in Bertie County, North Carolina, in 2015. There was no sign of a fort, but just outside the village wall the archaeologists found two dozen shards of English pottery at what’s been dubbed Site X. These pottery fragments represent some of the most compelling evidence of where the colonists actually went.

Site Y Yields More Compelling Evidence

The search continued in December 2019 at what’s been dubbed Site Y, yielding many more fragments of ceramics from different parts of Europe. The fragments, which come from vessels used for food preparation and storage, suggest the presence of long-term residents. Unlike temporary camps or trading posts, these archaeological signatures indicate permanent settlement and daily life activities.

The pottery finds at both sites tell a story of adaptation and survival. What has been found so far at Site Y in Bertie County appears to me to solve one of the greatest mysteries in Early American history, the odyssey of the ‘Lost’ colony, according to experts involved in the excavation. The evidence suggests the colonists dispersed into smaller groups rather than remaining as one large settlement.

The Blacksmith Shop Discovery That Sealed the Case

We found an entire blacksmith shop and the hammer scale and the slag and the vitriolized glass. All these byproducts of blacksmithing are there, which proves that they’re living and working on the site, announced Scott Dawson during recent excavations in Buxton. This discovery represents the most definitive proof yet that English colonists established permanent residences on Hatteras Island.

Forges were not temporary sites. Settlers wouldn’t have set one up only to move away shortly afterward. Thus, the presence of an English-style forge on Hatteras Island dating back to the 16th century is likely proof that Europeans stayed on the island as permanent residents. The sophisticated metalworking operation required investment, planning, and long-term commitment to the location.

Why the Croatoan Connection Makes Perfect Sense

John White and the colonists had made an agreement before White left for England. The colonists were to write where they were going if they left, and to put a mark over the inscription if they’d left in a hurry. Indeed, the carved “CROATOAN” seems to indicate the colonists had intended to head there, and the absence of a mark means there had been no hurry. This wasn’t a desperate message from people in distress—it was a forwarding address.

John White himself was sure that they had gone to Croatoan. Indeed, White had begun to sail to Croatoan after finding Roanoke empty, but he never completed the journey because of a storm. The colony’s governor knew exactly where his people had gone, but weather prevented him from reuniting with them.

The Practical Reality of Colonial Survival

Roanoke Island didn’t have much farming, and the Indigenous tribes grew corn on the mainland. So to feed themselves… they would have needed to either be fed by or move in with a native town, and the Croatoans are the most likely. The decision to relocate wasn’t mysterious—it was practical survival strategy based on established relationships and available resources.

The colonists arrived with limited supplies and faced the harsh realities of establishing a settlement in unfamiliar territory. Horton studies the Lost Colony, a group of about 120 English settlers who arrived on Roanoke Island in North Carolina’s Outer Banks in 1587. The colonists struggled to survive and sent their leader, John White, back to England for supplies. When those supplies were delayed by the Spanish Armada, survival depended on indigenous alliances.

The Multiple Settlement Theory

The First Colony researchers claim that the colonists must have dispersed into smaller groups, arguing that a single tribe could not have integrated 100 or more new residents. Possibly, a small group went to Croatoan Island in the fall or winter of 1587 to wait for John White to return while the remainder moved inland to the mouth of the Chowan River and Salmon Creek. This dispersal strategy would have increased survival chances while maintaining cultural connections.

Archaeological evidence supports this multi-site theory. Different locations show varying types of English artifacts, suggesting specialized groups settled in areas best suited to their skills and the local environment. Some groups focused on agriculture, others on trade, and still others on metalworking and craft production.

Scientific Dating Confirms the Timeline

Radiocarbon dating of the layer of dirt in which the hammer scale was found suggests its age aligns with the Lost Colony. This scientific verification eliminates speculation about later contamination or unrelated European presence. The dating evidence places the metalworking activities precisely within the timeframe when the colonists would have been establishing themselves in new locations.

We found it stratified … underneath layers that we know date to the late 16th or early 17th century. So we know that this dates to the period when the lost colonists would have come to Hatteras Island. The stratigraphic evidence provides additional confirmation that these aren’t random artifacts but part of a continuous occupation pattern.

The Academic Debate and Skepticism

Not all experts are convinced by the new evidence. I would like to see a hearth if we’re talking about forging activity. And even then, the hammer scale may be from Indigenous people’s repurposing of the colonists’ items for their own use, Ewen said, or it could even be trash from 16th-century explorers and settlers who stopped over while sailing the Gulf Stream up the East Coast. The hammer scale is just not doing it for me without good context, argues Charles Ewen, professor emeritus of archaeology at East Carolina University.

However, the weight of evidence continues to accumulate. We are very confident that these excavations are linked to the Roanoke colonies. We have considered all other reasonable possibilities and can find nothing else that fits the evidence, states the First Colony Foundation. The combination of multiple archaeological sites, consistent artifact patterns, and scientific dating creates a compelling case.

The Cultural Impact of Debunking the Mystery

The revelation that the Lost Colony was never actually lost challenges deeply embedded cultural narratives. Today, the “lost” Roanoke colony has become something of a cultural force in itself. There are various explanations as to what happened to the settlers, some of which have become a source of white nationalist pride. The truth offers a more complex but ultimately more human story of adaptation and cooperation.

This new understanding also highlights the sophisticated nature of indigenous societies and their capacity for integrating newcomers. Rather than the vanishing act of popular imagination, we see evidence of successful cross-cultural cooperation that allowed both communities to thrive together.

Looking Forward: What This Means for American History

Our motivation in doing this was not to find the Lost Colony, because nobody that has any academia at all considers them lost. What we did was prove what we already knew, so that hopefully we could reinstate these guys, and that textbooks would start teaching Croatoan is the old name of Hatteras Island and a tribe. The implications extend far beyond solving a historical puzzle—they challenge how we teach and understand early American history.

The story of successful integration between English colonists and the Croatoan people offers a different model for understanding colonial encounters. Rather than inevitable conflict or mysterious disappearance, we see evidence of practical cooperation, cultural exchange, and mutual survival strategies. This narrative provides important insights into the complex realities of early American settlement that extend far beyond the sensationalized mystery that has captured imaginations for centuries.