The Wales Window: A Silent Testimony from 4,000 Miles Away

Most people walking into Birmingham’s 16th Street Baptist Church know the tragic story of the 1963 bombing that killed four young girls. But John Petts, a stained glass artist from Llansteffan in Wales, was sickened by the attack and moved to make a gesture of kindness to the church in the aftermath. Collecting donations from churches and chapels across his country, he crafted what is now known as the Wales Window. This remarkable act of international solidarity remains one of the most beautiful yet unknown gestures in civil rights history.

The window stands as proof that the struggle for justice in Alabama reached hearts thousands of miles away. An aspect of the incident that far fewer people are aware of, however, is how it inspired an incredible act of generosity from people 4,000 miles away from Alabama. Even today, visitors pass by this stunning memorial without knowing its extraordinary backstory of cross-continental compassion.

Lowndes County: The Birthplace of the Black Panther Symbol

The Lowndes County Freedom Organization (LCFO), also known as the Lowndes County Freedom Party (LCFP) or Black Panther party, was an American political party founded during 1965 in Lowndes County, Alabama. The independent third party was formed by local African-American citizens led by John Hulett, and by staff members of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) under the leadership of Stokely Carmichael. This rural county, with its overwhelming Black population and complete white political control, became the unlikely birthplace of one of America’s most recognizable civil rights symbols.

The political symbol in Lowndes County when we went in there was for the white Democratic Party, The Dixiecrats, was a white rooster, and it had the motto around it that said, “White supremacy for the right.” They said, we need a mean black cat to run that white rooster out of this county. And that became the Black Panther. What many don’t realize is that they appropriated it from Clark College in Atlanta. It was their football mascot.

John Hulett: The Forgotten Sheriff Who Changed Everything

Lowndes County consists of a population of about 15,000 people. Out of these 15,000 people, 80 percent are Negroes, 20 percent white. The entire county is controlled entirely by whites. Into this environment stepped John Hulett, a local farmer who would become one of the most remarkable yet overlooked figures in civil rights history. It was 80 percent Black but only one eligible Black citizen out of 12,000 was registered to vote; he was Mr. John Hulett, who would help found LCFO.

Five years later, LCFP supporters elected John Hulett as sheriff, and Mr. Charles Smith, another local leader, as county commissioner. Local activist, John Jackson, became the mayor of Whitehall, a small town in Lowndes. Hulett’s victory represented something unprecedented – a Black sheriff in a county known as “Bloody Lowndes” for its violent suppression of Black citizens.

The Fear That Kept Families Silent for Generations

There was something in Alabama a few months ago they called fear. Negroes were afraid to move on their own; they waited until the man, the people whose place they lived on, told them they could get registered. They told many people, “Don’t you move until I tell you to move and when I give an order, don’t you go down and get registered.” This fear wasn’t imaginary – it was enforced through systematic economic terrorism.

Then all the people were being evicted at the same time and even today in Lowndes County, there are at least 75 families that have been evicted. There were other people who live on their own places who owe large debts, so they decided to foreclose on these debts to run Negroes off the place. These tactics created a climate where entire families lived in silence, knowing that speaking up could mean losing their homes and livelihoods.

The Armed Reality Behind Nonviolent Protest

This is a liberal sheriff, too, who is “integrated,” who walks around and pats you on the shoulder, who does not carry a gun. But at the same time, in the county where there are only 800 white men, there are 550 of them who walk around with a gun on them. They are deputies. This startling statistic reveals the militarized nature of white supremacist control that civil rights workers faced daily.

The reality on the ground was far more dangerous than many historical accounts suggest. SNCC members were losing faith in the nonviolent approach taken by other civil rights organizations, namely the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), and Carmichael found Lowndes’ rural black population armed and ready to defend themselves when necessary.

Fred Dickerson: Waiting 60 Years to Tell His Story

Public History Director Jessica O’Connor recounted her first interview with footsoldier Fred Dickerson as a perfect example of the importance of their work. “He greeted me at his door and said ‘you’re late’ and I went ‘nuh uh I was actually 20 minutes early, I’ve been sitting in your driveway’ and he said ‘I’ve been waiting for 60 years for someone to ask me about my experience with the Montgomery Bus boycott’ so I said, ‘Fred, it turns out we might be right on time,'”

Dickerson’s story represents thousands of foot soldiers whose experiences remain largely undocumented. For the past seven years, the Alabama African American Civil Rights Heritage Sites Consortium has traveled around Alabama, sharing lesser-known stories of the civil rights movement. These are the voices that fill in the gaps between the famous speeches and landmark court cases.

The Rural Alabama Health Crisis That Shaped Resistance

Rural Alabama offers a useful case study. Centering south-central Alabama, this paper will demonstrate how white control over rural health outcomes caused many Black Alabamians’ to cultivate a culture of survival over resistance throughout the mid-twentieth century. This devastating reality forced families to choose between activism and basic survival needs for their children.

Yet, the experiences of those who faced harsh repression, poverty, and displacement in the rural South do not emerge in these resistance narratives. As Nell Irvin Painter notes, scholars sometimes trace civil rights narratives with a sense of hope as they “find the story of black struggle ever so much more inspiring than that of white supremacist power.” The truth was often much harsher than the inspirational narratives suggest.

The Untold Stories Now at Risk of Being Lost Forever

NOW, AFTER LOSING THEIR FUNDING BECAUSE OF DOGE CUTS, THE CONSORTIUM IS AT RISK OF NOT BEING ABLE TO TELL THOSE STORIES. WE HAVE COLLECTED WELL OVER 100 STORIES, WHICH WE HAVE UPLOADED TO OUR DIGITAL ARCHIVE. THERE ARE AT LEAST DOUBLE THAT AMOUNT THAT ARE LEFT TO STILL RECORD The urgency of this moment cannot be overstated – as elderly foot soldiers pass away, their stories die with them.

EVERYTHING THAT WE NEED FINANCIALLY, HUMAN SERVICES, IDEAS, WE HAVE IT WITHIN OUR COMMUNITY. SO WE’RE CALLING UPON OUR COMMUNITY. COME ON. SO IN DO YOUR PART, DO YOUR PIECE. This grassroots approach mirrors the same community organizing that drove the original movement.

The Tuskegee Airmen’s Civil Rights Legacy

Tuskegee Human & Civil Rights Multicultural Center tells previously untold Civil Rights stories about the first African American U.S. military pilots, known as the ‘Tuskegee Airmen’, who flew with distinction during World War II. The blockbuster film ‘Red Tails’ by George Lucas tells their story. But the connection between these pioneering aviators and the broader civil rights movement runs deeper than most realize.

The Tuskegee Airmen proved Black excellence in military service, creating a foundation for arguments against segregation that would echo throughout the 1950s and 1960s. Their success provided concrete evidence that integration could work, influencing legal strategies and public opinion in ways that are rarely acknowledged in mainstream civil rights narratives.

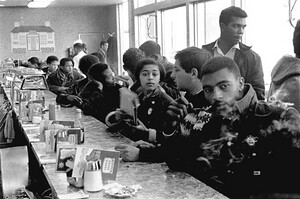

The Miles College Student Boycott That Preceded Birmingham

In the spring of 1962, students from Miles College boycott the downtown merchants in Birmingham, AL. This lesser-known student action actually preceded the famous Birmingham Campaign by a full year, demonstrating how young people were already organizing sophisticated economic pressure campaigns.

The Miles College boycott showed that students understood the power of economic leverage before it became a central strategy of the larger movement. These young activists developed tactics that would later be crucial to the success of more famous campaigns, yet their pioneering work remains largely unknown outside of local communities.

Shiloh’s Modern Civil Rights Victory

Shiloh’s flooding crisis reveals the limitations of the civil rights complaint system in addressing infrastructure-driven environmental injustice. This recent case shows how civil rights work continues in rural Alabama, often dealing with environmental racism that affects predominantly Black communities.

The federal resolution of Shiloh’s civil rights complaint represents a new chapter in Alabama’s civil rights story, one that addresses how decades of discriminatory infrastructure decisions continue to impact Black communities. Capital B is a nonprofit news organization dedicated to delivering Black-focused, independent, fact-based journalism that informs, inspires, and empowers our community. We work hard to bring you the stories that often go untold—stories that matter.

The Indigenous Roots of the Black Panther Symbol

During the 18th and 19th centuries, all five major Southern nations or confederations of Indigenous peoples — the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek (Muscogee) and Seminole — were subjected to a strategy of “civilization” by the U.S. that tried to make some members of the nation into slaveholders. As soon as slavery was introduced into the U.S. Southeast, enslaved people began to liberate themselves by escaping to swampy lands near the Alabama River to live in “maroon” lands and secret encampments of Native peoples. Though no direct connection can be traced, it seems possible that the appeal of the black panther to local Lowndes County people might rest in its Indigenous roots — the fact that the Panther gens, the Katsalgi, was one of the primary Creek social units.

This connection suggests that the choice of the black panther as a symbol may have deeper historical and cultural roots than previously understood. The intersection of Indigenous and African American resistance in Alabama creates layers of meaning that most people never discover.

The 20 Heritage Sites Preserving Hidden Stories

Explore the stories of 20 sites of worship, lodging, and civic engagement in Birmingham, Montgomery, and across the Black Belt that played significant roles in the African-American struggle for freedom—from Reconstruction to the Civil Rights Movement and beyond. These sites represent a network of resistance that operated far beyond the famous churches and meeting halls that dominate historical narratives.

Our mission is to promote the legacy of the civil rights movement by preserving historic buildings, protecting authentic stories, and empowering communities. We have a vision to instruct, inspire and empower each generation to use civil rights history as a tool for community revival, renewal, and revitalization. Each location holds stories that could change how we understand the movement’s complexity and reach.

Conclusion: The Stories Still Being Discovered

On this Pilgrimage, you’ll visit historic sites, walk about the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, and meet unsung heroes and foot soldiers of the Civil Rights Movement. meet unsung heroes and foot soldiers of the Civil Rights Movement. The work of uncovering these stories continues, with new discoveries happening regularly as researchers gain access to previously untold experiences.

Alabama’s civil rights story extends far beyond the famous moments captured in textbooks and documentaries. In small towns, rural counties, and forgotten corners of the state, ordinary people made extraordinary sacrifices that changed the course of American history. Their stories wait in archives, family memories, and the testimonies of aging foot soldiers. What untold story from your own community might be waiting to change how we understand this pivotal chapter in American history?