Abraham Lincoln: The Architect of Reconstruction’s Foundation

Abraham Lincoln was assassinated in April 1865, just as the Civil War was ending, but his vision for Reconstruction continued to influence the era even after his death. In his final speech on April 11, 1865, Lincoln expressed his belief that some Black Americans—particularly “the very intelligent” and those who had served in the Union Army—should be granted the right to vote. Initially, Lincoln had announced a lenient plan that limited suffrage to whites as a way to attract Southern Confederates back to the Union. However, by the end of his life, Lincoln had evolved to favor extending voting rights to educated blacks and former soldiers.

Just 41 days before his assassination, Lincoln used his second inaugural address to signal reconciliation between North and South, famously declaring: “With malice toward none; with charity for all… let us strive to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation’s wounds.” Lincoln’s greatest gesture, and certainly his final one before he was murdered, was the establishment of the Freedmen’s Bureau—as four million slaves were set free and would not have had any place to stay, sleep, or eat without this concept.

Andrew Johnson: The Obstacle to Radical Progress

The assassination of Abraham Lincoln propelled Vice President Andrew Johnson into the executive office in April 1865. Johnson, a states’-rights strict constructionist and unapologetic racist from Tennessee, offered southern states a quick restoration into the Union. In personality and outlook, President Andrew Johnson was ill-suited for the responsibilities he shouldered following Lincoln’s assassination. A lonely, stubborn man, he was intolerant of criticism and unable to compromise, lacking Lincoln’s political skills and keen sense of Northern public opinion.

Johnson vetoed Radical Republican bills, pardoned Confederate leaders, and allowed Southern states to enact draconian Black Codes that restricted the rights of freedmen. His racist view of Reconstruction did not include the involvement of blacks in government, and he refused to heed Northern concerns when Southern state legislatures implemented these restrictive laws. Although Johnson had supported emancipation during the war, he held deeply racist views and believed African Americans had no role to play in Reconstruction, positioning himself as a spokesman for poor white farmers of the South.

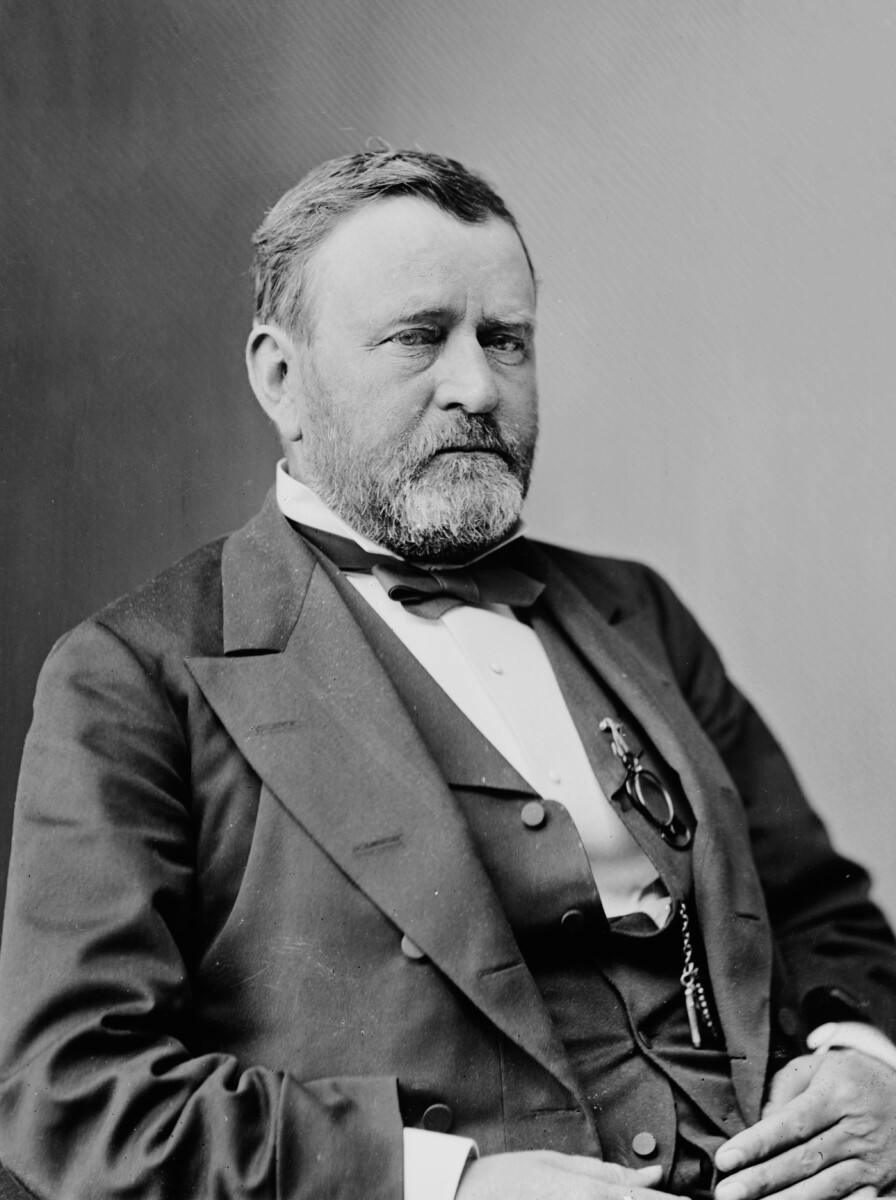

Ulysses S. Grant: The Military Leader Turned Reconstruction President

Under Johnson’s successor, President Ulysses S. Grant, Radical Republicans enacted additional legislation to enforce civil rights, such as the Ku Klux Klan Act and Civil Rights Act of 1875. However, resistance to Reconstruction by Southern whites and its high cost contributed to its losing support in the North. Grant’s acquittal of Johnson during impeachment proceedings made his nomination as the party’s presidential candidate inevitable. The nation’s greatest war hero initially had supported Johnson’s policies but eventually came to side with Congress, though Radicals worried that he lacked strong ideological convictions.

Grant was empowered by Congress to stop the Ku Klux Klan’s violence through the Third Enforcement Act of 1871, which allowed federal troops to make hundreds of arrests in South Carolina, forcing perhaps 2,000 Klansmen to flee the state. Grant’s administration was running a race against time—not only regarding white southerners displaced from power, but also the flood of his cronies whom he had trusted. Yet Grant did yeoman service to Lincoln’s dream by suggesting that justice in an open society would eventually become more likely in the long term.

Thaddeus Stevens: The Radical Republican Firebrand

Thaddeus Stevens (1792-1868) was an American politician and lawyer who served as a member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Pennsylvania, becoming one of the leaders of the Radical Republican faction. A fierce opponent of slavery and discrimination against black Americans, Stevens sought to secure their rights during Reconstruction while leading the opposition to President Andrew Johnson and serving as chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee during the Civil War. Stevens stated that what was needed was a “radical reorganization of southern institutions, habits, and manners,” arguing alongside fellow radicals that southern states should be treated like conquered provinces without constitutional rights.

The difference in views caused an ongoing battle between Johnson and Congress, with Stevens leading the Radical Republicans. After gains in the 1866 election, the radicals took control of Reconstruction away from Johnson, and Stevens’s last great battle was to secure articles of impeachment against Johnson in the House, serving as a House manager in the impeachment trial. Stevens understood far better than most of his contemporaries that fully uprooting slavery meant overthrowing the South’s economic system and challenging property rights—first the right of some human beings to own others, but also beyond it.

Charles Sumner: The Senate’s Radical Voice

The Radical Republicans were led by Thaddeus Stevens in the House of Representatives and Charles Sumner in the Senate. In Congress, the most influential Radical Republicans were U.S. Senator Charles Sumner and U.S. Representative Thaddeus Stevens, who led the call for a war that would end slavery. In 1867, Pennsylvania Congressman Thaddeus Stevens and Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner led the campaign for full voting rights for African Americans across the nation.

Led by Charles Sumner of Massachusetts in the Senate and Representative Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania in the House, this faction within the Republican Party had roots in the antebellum abolitionist movement and had long sought to destroy the institution of slavery and protect the rights of African Americans. The Radicals believed that the federal government could guarantee equal rights for all through legislation, constitutional amendments, and enforcement powers of the executive branch, and although they were a vocal minority within the Republican Party, they were well-positioned to drive the congressional Reconstruction agenda.

Oliver Otis Howard: The “Christian General” of the Freedmen’s Bureau

Headed by Union Army General Oliver O. Howard, the Freedmen’s Bureau started operations in 1865. Oliver Otis Howard was appointed as the first Freedmen’s Bureau Commissioner, and Howard University was named for him when it was founded in Washington, D.C., in 1867. O. O. Howard, leader of the newly established Freedmen’s Bureau, understood the challenges of securing personal liberty and equal rights for African Americans. Born in Maine on November 8, 1830, Oliver Otis Howard graduated from Bowdoin College in 1850 and the U.S. Military Academy at West Point in 1854, serving as a professor of mathematics at West Point and a staunch abolitionist before the Civil War.

Oliver Otis Howard, a staunch supporter of African American education, cofounded Howard University in Washington, D.C., in 1867 through an act by Congress, using Freedmen’s Bureau funds to purchase land and construct several campus buildings. The Bureau’s mission was to help solve everyday problems of newly freed slaves, such as obtaining food, medical care, communication with family members, and jobs. Between 1865 and 1869, it distributed 15 million rations of food to freed African Americans and 5 million rations to impoverished whites.

Hiram Revels: The First African American Senator

On February 25, 1870, visitors in the U.S. Senate gallery burst into applause when the new Republican senator from Mississippi entered the chamber. This man was no ordinary senator—he was Hiram R. Revels, the first African American ever to sit in either house of Congress. Hiram Rhodes Revels was born in North Carolina on September 27, 1827, to free black parents and was a free man his entire life. He attended Union County Quaker Seminary in Indiana and Darke Seminary in Ohio before being ordained as a minister in the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church in 1845.

Hiram Revels, the first Black elected to the U.S. Senate (taking the Senate seat from Mississippi that had been vacated by Jefferson Davis in 1861), was born free in North Carolina and attended college in Illinois. He worked as a preacher in the Midwest in the 1850s and as a chaplain to a Black regiment in the Union Army before going to Mississippi in 1865 to work for the Freedmen’s Bureau. Revels’ term expired in 1871 and he became the president of Alcorn Agricultural and Mechanical College (now Alcorn State University) in Mississippi, retiring in 1882 and living until January 16, 1901.

Blanche K. Bruce: The First Full-Term African American Senator

Hiram Revels was the first African American to serve in Congress, but he did not serve a full six-year Senate term. That distinction fell to Blanche Kelso Bruce, who represented the same state—Mississippi—in the Senate from 1875 to 1881. Unlike Revels, Bruce, a native of Virginia, was born into slavery. Blanche K. Bruce, elected to the Senate in 1875 from Mississippi, had been enslaved but received some education.

Like Revels before him, Bruce worked diligently in the Senate to support freed men and women in Mississippi. In 1878 he tried to pass legislation to desegregate the U.S. Army and two years later demanded an investigation into the brutal hazing of black West Point cadet Johnson Whittaker, supporting black colleges and opposing legislation such as the Chinese Exclusion Act that sought to discriminate against other minority groups. On February 14, 1879, Bruce briefly presided over the Senate, making him the first African American ever to do so. The following year, in 1880, he unexpectedly received eight votes for vice president at the Republican National Convention in Chicago, making him the first African American to receive votes for national office at a major party convention.

The Radical Republicans: The Engine of Change

The Radical Republicans were a group of politicians who formed a faction within the Republican party that lasted from the Civil War into the era of Reconstruction. They were led by Thaddeus Stevens in the House of Representatives and Charles Sumner in the Senate. Radical Republicans were a faction within the Republican Party that emerged in the mid-1850s, primarily advocating for the complete abolition of slavery and the protection of civil rights for African Americans. Key figures included Representative Thaddeus Stevens and Senator Charles Sumner, who sought a more aggressive approach to Reconstruction following the Civil War, and the group believed that the war should be leveraged not only to preserve the Union but also to eradicate slavery permanently.

Throughout the war, the group often criticized President Lincoln and pressured him to support their legislation. While President Lincoln wanted to fight the war largely for the preservation of the Union, the Radical Republicans believed the primary reason for fighting was for the abolition of slavery, and most of their critiques toward Lincoln were targeted at his lack of aggression in his policies, especially regarding rights for Blacks. While the Radical Republicans dominated the late 1860s, their power began to dwindle in the early 1870s. At that point, many political leaders believed that the era of Reconstruction was successfully completed and no longer needed Radical supervision, and some Radicals, including Charles Sumner, agreed with this idea and left the Radical Republican faction to join the moderates.

Frederick Douglass: The Voice of Freedom

Frederick Douglass appeared alongside Blanche Kelso Bruce and Hiram Revels in a color lithograph titled “Heroes of the Colored Race” from 1881, showing his continued prominence as a leader during the Reconstruction era. Though not holding elected office during Reconstruction, Douglass remained a powerful voice for African American rights and was instrumental in shaping public opinion about the need for civil rights legislation.

These Black activists bitterly opposed the Reconstruction policies of President Andrew Johnson, which excluded Black people from southern politics and allowed state legislatures to pass restrictive “Black codes” regulating the lives of freed men and women. Fierce resistance to these discriminatory laws, as well as growing opposition to Johnson’s policies in the North, led to a Republican victory in the U.S. congressional elections of 1866 and to a new phase of Reconstruction that would give Black Americans a more active role in political, economic and social life of the South.

Edwin Stanton: The Radical Republican in Lincoln’s Cabinet

Lincoln put all factions in his cabinet, including Radicals like Salmon P. Chase (Secretary of the Treasury), whom he later appointed Chief Justice, James Speed (Attorney General) and Edwin M. Stanton (Secretary of War). President Andrew Johnson told Ulysses S. Grant that he intended to fire Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, who had been a consistent opponent of the president and was close to the Radical Republicans who dominated Congress. Stanton had refused to resign and Congress had supported him through the Tenure of Office Act, which required the consent of Congress to removals.

When, in February 1868, Johnson removed Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton in violation of the recently-enacted Tenure of Office Act, he was impeached by the House of Representatives. The Senate failed by one vote to remove him from office. Stanton’s defiance of Johnson and his support for Radical Reconstruction policies made him a key figure in the struggle between the executive and legislative branches during this tumultuous period.

Rutherford B. Hayes: The President Who Ended Reconstruction

The 1876 presidential election was marked by Black voter suppression in the South, and the result was close and contested. An Electoral Commission resulted in the Compromise of 1877, which awarded the election to Republican Rutherford B. Hayes on the understanding that federal troops would cease to play an active role in regional politics. The Compromise of 1877 closed with a national consensus, except on the part of former slaves, that the war had finally ended. With the withdrawal of federal troops, however, white men retook control of every Southern legislature, and the Jim Crow era of disenfranchisement and legal segregation was ushered in.

Historians are less sure about the results of postwar Reconstruction, especially regarding the second-class citizenship of the freedmen and their poverty. Hayes’s presidency marked the effective end of Reconstruction, though recent scholarship, including work published in 2024, continues to examine how different figures like Grant pressed through enforcement acts to uphold the 14th Amendment’s recognition of Black citizenship.

The Reconstruction era fundamentally transformed American society through the actions of these remarkable individuals. From Lincoln’s initial vision to the radical agenda of Stevens and Sumner, from the pioneering service of Revels and Bruce to the dedicated work of Howard and the Freedmen’s Bureau, these figures shaped a period that would define civil rights struggles for generations to come. Their successes and failures continue to influence American democracy today, reminding us that the work of creating a more perfect union requires constant vigilance and commitment.