The Preemption Act of 1841: When Squatters’ Rights Became Legal Reality

Long before the famous Homestead Act, there was a revolutionary law that fundamentally changed how Americans could claim land on the frontier. The Preemption Act of 1841 was a significant piece of legislation in the United States that aimed to facilitate land ownership for settlers in the expanding western territories. It established the right for squatters—individuals who occupied and cultivated public lands—to purchase up to 160 acres at a minimum price, provided they met certain conditions, including erecting a dwelling on the land. This remarkable law essentially legalized what had been considered trespassing for decades.

The Preemption Act of 1841 recognized that settlement prior to purchase did not constitute trespassing, and that the use of the land for settlement was more important than for raising revenue, although the latter goal had been the original objective of selling off the public lands. Under the law, any adult citizen (or an alien who had declared his intention to become a citizen) who had occupied, cultivated, and erected a dwelling on the public lands could purchase a tract of up to 160 acres at the minimum price. Ultimately, the Preemption Act laid foundational principles that would later be expanded upon in the Homestead Act of 1862, promoting broader access to land ownership for settlers.

The Desert Land Act of 1877: The Forgotten Gateway to Western Expansion

The Desert Land Act is a United States federal law which was passed by the United States Congress on March 3, 1877, to encourage and promote the economic development of the arid and semiarid public lands within certain states of the Western states. Through the Act, United States citizens, or those declaring an intent to become a citizen, over the age of 21 may apply for a desert-land entry to irrigate and reclaim the land. This law offered something unprecedented: massive amounts of land at dirt-cheap prices if settlers could prove they could make it productive.

The Act allowed anyone to purchase 640 acres of land for 25 cents per acre if the land was irrigated within three years of filing. A rancher could receive title to the land any time within the three years upon proof of compliance with the law and payment of one additional dollar per acre. What makes this law particularly fascinating is that it’s still on the books today. At the same time it refused to repeal the Desert Land Act and the Carey Act of 1894 under which the federal government could make up to one million acres of public desert lands available to specific states. “Today,” in the words of Paul Herndon of the BLM, “these two laws stand as a beacon of hope for thousands of Americans who continue to look to the Federal Government for low-cost land.

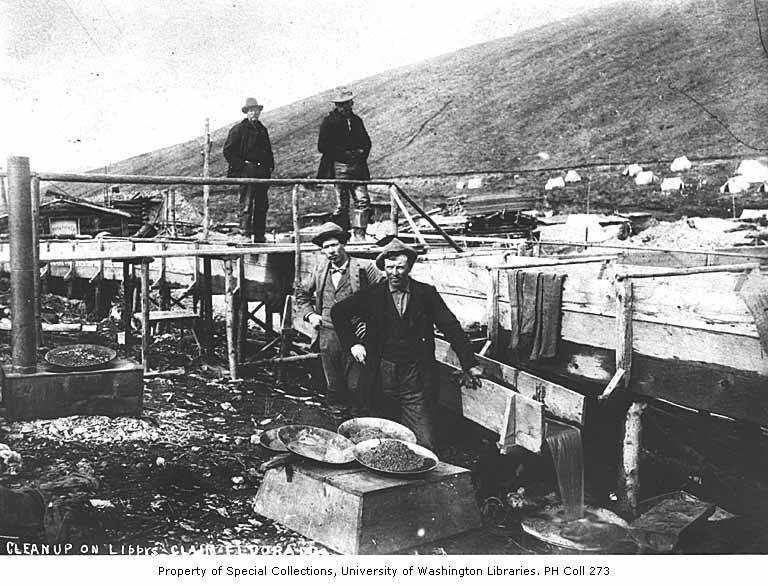

The Mining Law of 1872: America’s Most Generous Corporate Giveaway

The General Mining Act of 1872 is a United States federal law that authorizes and governs prospecting and mining for economic minerals, such as gold, platinum, and silver, on federal public lands. This law, approved on May 10, 1872, codified the informal system of acquiring and protecting mining claims on public land, formed by prospectors in California and Nevada from the late 1840s through the 1860s, such as during the California Gold Rush.

Here’s where things get truly shocking for modern Americans: A miner or a mining company can stake a claim for $2.50 to $5.00 per acre, pay their $100 annual fee, and owe no other money to the federal treasury regardless of the actual value of the minerals extracted at the claim. Critics argue that the federal government is giving away billions of dollars of taxpayer money in what amounts to a massive subsidy for mining. The law remains virtually unchanged since 1872, despite the fact that mining technology and economics have been revolutionized since then. Although the practices for open mining on public land were more-or-less universal in the West, and supported by state and territorial legislation, they were still illegal under existing federal law. At the end of the American Civil War, some eastern congressmen regarded western miners as squatters who were robbing the public patrimony, and proposed seizure of the western mines to pay the huge war debt.

The Timber Culture Act of 1873: America’s Failed Forest Initiative

The Timber Culture Act granted up to 160 acres of land to a homesteader who would plant at least 40 acres (revised to 10) of trees over a period of several years. This quarter-section could be added to an existing homestead claim, offering a total of 320 acres to a settler. The concept was brilliant in theory: encourage tree planting in the treeless Great Plains while rewarding settlers with more land. In reality, it became one of America’s most spectacular environmental failures.

The Timber Culture Act of 1873 was another law that encouraged homesteading and the planting of trees in the west. If a settler planted 40 acres of timber (reduced to 10 acres in 1878) and fostered their growth for 10 years, the individual was entitled to that quarter section of land. The Timber Culture Act also permitted homesteaders who occupied their land for three years, with one acre of trees under cultivation for two of those three years, to receive a patent to the land. The law was eventually repealed in 1882. The law’s failure stemmed from the harsh reality that most of the Great Plains simply couldn’t support extensive tree growth without massive irrigation systems that didn’t yet exist.

The Timber and Stone Act of 1878: Resource Extraction Made Legal

Timber and Stone Act (1878): This act enabled individuals to purchase land that was considered unfit for farming but valuable for its timber or mineral resources. They could buy 160 acres at $2.50 per acre, promoting the extraction of valuable resources in the West. This law created a peculiar category of land ownership that prioritized industrial exploitation over agricultural settlement.

The Timber and Stone Act represented a dramatic shift in federal land policy. Together, these acts offered more significant opportunities for land acquisition compared to the Homestead Act, which limited settlers to 160 acres. The overarching goal of all these acts was to promote westward expansion and settlement by addressing the specific needs of different environments in the West. What made this law particularly controversial was that it explicitly acknowledged that not all western land was suitable for farming, yet the government was still determined to transfer ownership to private hands.

The Stock Raising Homestead Act of 1916: The Last Great Land Giveaway

Stock Raising Homestead Act (SRHA) lands are different from other federal lands in that the United States owns the mineral estate, but not the surface estate. Patents issued under the SRHA and Homestead Act entries patented under the SRHA reserve the mineral estate to the United States along with the right to enter, mine, and remove any reserved minerals that may be present in the mineral estate.

This 1916 law was the government’s acknowledgment that the standard 160-acre homestead simply couldn’t support livestock ranching in the arid West. The act allowed for homesteads of 640 acres, but with a crucial catch that continues to create legal complications today. The federal government retained all mineral rights, meaning that if oil, gas, or valuable minerals were discovered later, the government could essentially take back portions of the land for extraction purposes. This created a bizarre form of split ownership that has led to countless legal disputes over the past century.

The Carey Act of 1894: States as Land Developers

the Carey Act of 1894 under which the federal government could make up to one million acres of public desert lands available to specific states. This law essentially turned state governments into real estate developers, allowing them to sell federal desert lands to private individuals and companies for reclamation projects.

The Carey Act represented a dramatic departure from previous land policies because it inserted state governments as middlemen between federal land ownership and private development. States could select up to one million acres of federal desert land within their boundaries and then arrange for private companies to develop irrigation systems. Once the irrigation was complete, the land would be sold to settlers. This law was particularly significant in states like Idaho, where massive irrigation projects transformed vast stretches of desert into productive farmland.

The Indian Homestead Act of 1884: Forced Assimilation Through Land Policy

The 1862 Homestead Act did not include Indigenous peoples, so Congress passed the Indian Homestead Act to give Native family heads the opportunity to purchase homesteads from unclaimed public lands. This was under the condition that the individual relinquished their tribal identity and relations, along with the land improvement requirements. The federal land title was not officially granted to Native Americans until a period of five years had passed. Because the US government did not issue fee waivers, many poor non-reservation Natives were unable to pay filing fees to claim homesteads.

This law represented one of the most insidious aspects of frontier legislation because it forced Native Americans to abandon their cultural identity as the price for land ownership. The act was part of a broader assimilation policy designed to break up tribal structures and force Native Americans to adopt European-American agricultural practices. The requirement that Native Americans “relinquish their tribal identity and relations” essentially meant cultural suicide as the price for participating in the American dream of land ownership.

The Kinkaid Act of 1904: Nebraska’s Special Deal

One of the most geographically specific land laws was the Kinkaid Act, which applied only to a portion of western Nebraska. This law allowed homesteads of 640 acres instead of the standard 160, recognizing that the sandhills region of Nebraska required larger parcels to support ranching operations. The Kinkaid Act was named after Congressman Moses Kinkaid of Nebraska and represented successful regional lobbying for special treatment under federal land law.

What made the Kinkaid Act remarkable was its explicit recognition that “one size fits all” land policy didn’t work across the diverse landscapes of the American frontier. The law acknowledged that the sandy soil and sparse rainfall of western Nebraska made small-scale farming impossible, requiring larger holdings for successful livestock ranching. This represented a significant evolution in federal thinking about land use and regional environmental differences.

The Enlarged Homestead Act of 1909: Doubling Down on Dry Land Farming

The Enlarged Homestead Act of 1909 was the federal government’s response to growing pressure from western settlers who argued that 160 acres simply wasn’t enough to make a living in the arid regions of the frontier. This law allowed homesteaders to claim 320 acres in certain areas, effectively doubling the size of standard homestead claims.

The law applied to lands that were determined to be non-irrigable and suitable only for dry land farming or grazing. Settlers still had to fulfill the same residency and cultivation requirements as under the original Homestead Act, but they were given twice as much land to work with. The law was particularly important in states like Montana, Wyoming, Colorado, and the Dakotas, where rainfall was insufficient for traditional farming methods. However, even 320 acres often proved inadequate for successful dry land farming, leading to widespread farm failures during periods of drought.

The Reclamation Act of 1902: Engineering the Desert

The Reclamation Act of 1902, also known as the Newlands Act, represented a fundamental shift in federal land policy from simply giving away land to actively engineering its productivity. This law created the federal reclamation program, which funded massive irrigation projects throughout the western United States using revenue from the sale of public lands.

The act established the principle that the federal government would build dams, canals, and irrigation systems to make desert lands productive, then sell water rights to settlers to recoup the construction costs. This law led to the creation of some of America’s most famous infrastructure projects, including the Roosevelt Dam in Arizona and the Shoshone Dam in Wyoming. The Reclamation Act fundamentally changed the relationship between federal land policy and western development, transforming the government from a passive land distributor into an active landscape engineer.

The Federal Land Policy and Management Act of 1976: The End of an Era

Unheralded, almost unnoticed, Congress in 1976 repealed the Homestead Act. The Federal Land Policy and Management Act (FLPMA) of 1976 officially ended the homestead era and established the modern framework for federal land management. This law declared that the federal government would retain ownership of its remaining public lands rather than continuing to dispose of them to private parties.

Federal Land Policy & Management Act of 1976 (FLPMA) This Act did not amend the 1872 law, but did affect the recordation and maintenance of claims. The BLM is authorized to charge cost recovery fees under the Federal Land Policy and Management Act of 1976 (FLPMA) and the 2005 Cost Recovery Rule. FLPMA represented a complete philosophical reversal from the disposal policies that had dominated American land law since the founding of the republic. Instead of viewing public land as a resource to be transferred to private ownership, the federal government now committed to permanent stewardship of vast western landscapes.

The Lasting Legacy of Lost Laws

The frontier laws that shaped American expansion created a complex web of land ownership patterns that continue to influence western landscapes today. The perennial problems of too little water and a lack of adequate financing seem to have finally spelled its doom in Utah, as virtually everywhere else. With its passing still another chapter of America’s frontier history has been irrevocably closed. While most Americans focus on the famous Homestead Act, these lesser-known laws often had equally profound impacts on settlement patterns, resource extraction, and environmental management.

Perhaps most remarkably, some of these “lost” laws aren’t actually lost at all—they continue to operate today, creating modern legal and environmental challenges that lawmakers of the 1870s could never have imagined. The Mining Law of 1872 still governs mineral extraction on federal lands, while the Desert Land Act continues to offer opportunities for land acquisition in several western states. These legislative relics from America’s frontier past remain active forces in contemporary land use debates, proving that the frontier’s legal legacy is far from extinct.