The Geographic Mix-Up That Confuses History Buffs

Here’s something that might surprise you: when people talk about America’s most famous “lost colony,” they’re usually thinking of the wrong state. The Lost Colony mystery that has captivated Americans for centuries actually happened in North Carolina, not Maryland, and it remains one of the great unsolved mysteries of American history. While Maryland certainly has its own colonial settlements and historical mysteries, the famous disappearing colonists were part of Sir Walter Raleigh’s attempts to colonize North Carolina, specifically on Roanoke Island in 1587.

But here’s where it gets interesting for Maryland folks. Maryland’s St. Mary’s Fort is actually the fourth-oldest English settlement in North America, coming after Jamestown, Plymouth, and Massachusetts Bay. The confusion often stems from the fact that both colonies faced similar challenges and both have elements of mystery surrounding their early years.

Maryland’s Real Colonial Story Gets Overshadowed

The settlement where Maryland’s first fort was located was named St. Mary’s City, serving as Maryland’s first capital for more than 50 years until the site was abandoned after Annapolis became the capital of the Maryland colony in 1694. For more than 300 years, St. Mary’s was left alone, with the fort’s buildings decaying and the area being reclaimed by nature as an open meadow. Unlike the vanishing act at Roanoke, Maryland’s colonists didn’t disappear – they just moved their capital.

Archaeologists had been looking for the site of St. Mary’s Fort since the 1930s, but it wasn’t until 2017 that archaeologist Travis Parno, director of research and collections for Historic St. Mary’s City, took up the search. This Maryland mystery was actually solved recently, unlike its more famous North Carolina counterpart.

The Real Lost Colony Mystery Gets Solved in 2024

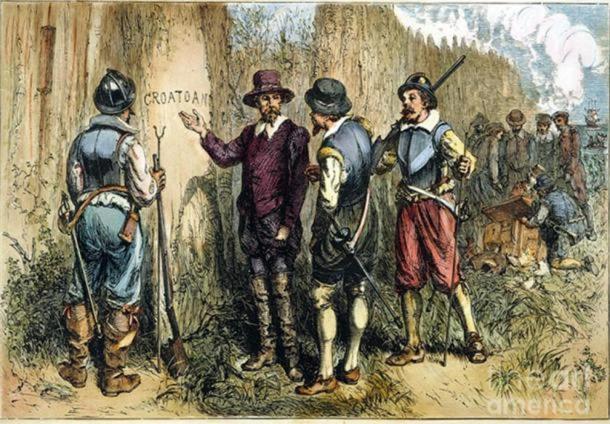

While Maryland doesn’t have a true “lost colony,” the actual Lost Colony mystery has seen some fascinating developments. Archaeologists believe they may have finally solved the 435-year mystery of America’s first English settlement, known as the “lost colony” of Roanoke, thanks to tiny flakes of rusted metal called hammerscales that are barely larger than grains of rice and are byproducts of metal forging dating back to the 16th Century.

During a recent speech at the Roanoke River Maritime Museum in Plymouth, North Carolina, author and president of the Croatoan Archaeological Society Scott Dawson announced his discovery, having been searching Hatteras for evidence to support his theory that the “Lost Colony of Roanoke” was never lost at all. It’s like finding out that the person you thought was missing was just living in the next town over all along.

The Hammerscale Evidence Changes Everything

The hammerscales are shavings that are a byproduct of iron-forging techniques that would have been unknown to the Croatoan tribe, but English settlers would have been using the blacksmithing techniques that produced hammerscale. This is metal that has to be raised to a relatively high temperature, requiring technology that Native Americans at this period did not have.

The evidence was found stratified underneath layers that date to the late 16th or early 17th century, so researchers know that this dates to the period when the lost colonists would have come to Hatteras Island. Think of it like archaeological layered cake – the deeper you go, the older the ingredients get.

DNA Projects Hunt for Descendants

Today, the Lost Colony DNA projects continue to build membership, with researchers hopeful that every new person who joins the Y DNA project could be “the one,” while English records continue to be transcribed and added to online databases, becoming accessible through services like Ancestry, MyHeritage and FindMyPast. Identifying the colonists and their families in England remains the key to solving the mystery of the fate of the Lost Colony, though those records won’t solve it alone.

Given that colonist surnames are reported among the Lumbee, it’s possible that the Y DNA of those families could point the way back to their English roots. It’s fascinating how modern technology can potentially solve centuries-old mysteries through genetic breadcrumbs.

Two Archaeological Teams Find Different Answers

Two independent teams found archaeological remains suggesting that at least some of the Roanoke colonists might have survived and split into two groups, with one team excavating a site near Cape Creek on Hatteras Island around 50 miles southeast of the Roanoke Island settlement, while the other is based on the mainland about 50 miles to the northwest. Cape Creek, located in a live oak forest near Pamlico Sound, was the site of a major Croatoan town center and trading hub, where in 1998 archaeologists stumbled upon a 10-carat gold signet ring engraved with a lion or horse, believed to date to the 16th century.

Recently, researchers found a small piece of slate that seems to have been used as a writing tablet and part of the hilt of an iron rapier similar to those used in England in the late 16th century, along with a slate bearing a small letter “M” found alongside a lead pencil, plus an iron bar and large copper ingot buried in layers dating to the late 1500s.

The Croatoan Connection Gets Stronger

Croatoan was the name of a neighboring island and the name of a Native American tribe residing there, presently known as Hatteras Island, though White tried to make the expedition 50 miles south to the island but a lack of provisions hampered his plans. Researchers have found thousands of artifacts showing a mix of English and native life roughly four-to-six feet deep in the soil, with parts of swords, rings, writing slates, gun parts and glass in the same layer as Indian pottery and arrowheads.

Documents from the English colony of Jamestown show the Roanoke colony did leave their camp to live with their native friends, and more than a century later, English explorer John Lawson found natives with blue eyes who recounted they had ancestors who could “speak out of a book”. That’s like finding people today who remember their great-grandparents talking about the old country.

The Marketing Campaign Theory

According to researcher Scott Dawson, “We don’t get this kind of lost mythology until the 1930s Lost Colony play production started – that’s the first time anybody ever referred to them as lost. It didn’t make a play about a mystery — they created a mystery with a play”. Dawson asserts that there was no mystery at all, the colonists were never lost, and the whole story is merely “a marketing campaign”.

This perspective completely flips the traditional narrative on its head. Instead of tragic disappearance, we might be looking at successful integration. It’s like discovering that someone you thought had vanished actually just changed their phone number and moved to a different neighborhood.

Site X and Site Y Reveal Split Groups

The First Colony Foundation announced that “compelling evidence” has been found that settlers from the colony lived at a site along Salmon Creek, near the Chowan River in Bertie County, for several years, calling the location Site Y. The remnants are similar to another location named Site X which was excavated several years ago, with both Sites X and Y being a couple of miles apart from each other and both locations near the Algonkian Indian town Mettaquem.

Foundation researchers used ground-penetrating radar and excavations at both sites, uncovering ceramic pieces archaeologists identified as Elizabethan artifacts, with findings suggesting a small number of colonists, perhaps an extended family and a few indentured servants, lived there.

The Skeptics Aren’t Convinced Yet

Some experts are unconvinced and say more evidence is needed, with one researcher noting that the archaeological and historical evidence does not clarify what happened to the Lost Colony. However, the mystery might be solved someday, particularly “if we could find European burials that we could tie to the 16th century with European materials and not trade items”.

It’s the classic scientific dilemma – extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence. Even with hammerscales and Tudor Rose emblems, some researchers want to see actual bodies or more definitive proof before declaring the mystery solved.

What This Means for American History

The colony’s disappearance became America’s oldest unsolved mystery, with 115 English settlers arriving on Roanoke Island to start a new life. As Dawson puts it, “We finally had that ‘smoking gun’ evidence, so there is no need to keep regurgitating the fictional story that no one knows what happened to them”.

If the new archaeological evidence holds up to scrutiny, it means one of America’s most enduring mysteries wasn’t really a mystery at all – just a story that got better with each telling. The colonists didn’t vanish into thin air; they did what many successful immigrants do: they adapted, integrated, and built new lives in their adopted homeland.

The Real Maryland Mystery Worth Investigating

While Maryland might not have the famous “Lost Colony,” it has plenty of its own historical puzzles worth exploring. Historic London Town and Gardens in Edgewater, Maryland is the site of a former European settlement and port town where a bustling tobacco trade and ferry crossing flourished along the Maryland waterways 300 years ago. Unlike the dramatic disappearance narrative of Roanoke, Maryland’s colonial settlements evolved and transformed rather than vanishing.

Maybe that’s the real lesson here – sometimes the most interesting stories aren’t about mysterious disappearances but about successful adaptations and cultural blending that happened right under our noses.

The truth is, Maryland doesn’t have its own “Lost Colony” mystery like North Carolina’s famous Roanoke settlement. But the recent archaeological breakthroughs in solving the Roanoke puzzle show us how modern science can finally answer questions that have puzzled historians for centuries. Whether it’s hammerscales in North Carolina soil or DNA projects tracing colonial bloodlines, we’re getting closer to understanding what really happened to America’s earliest English settlers. Sometimes the biggest mystery is why we called it a mystery in the first place.