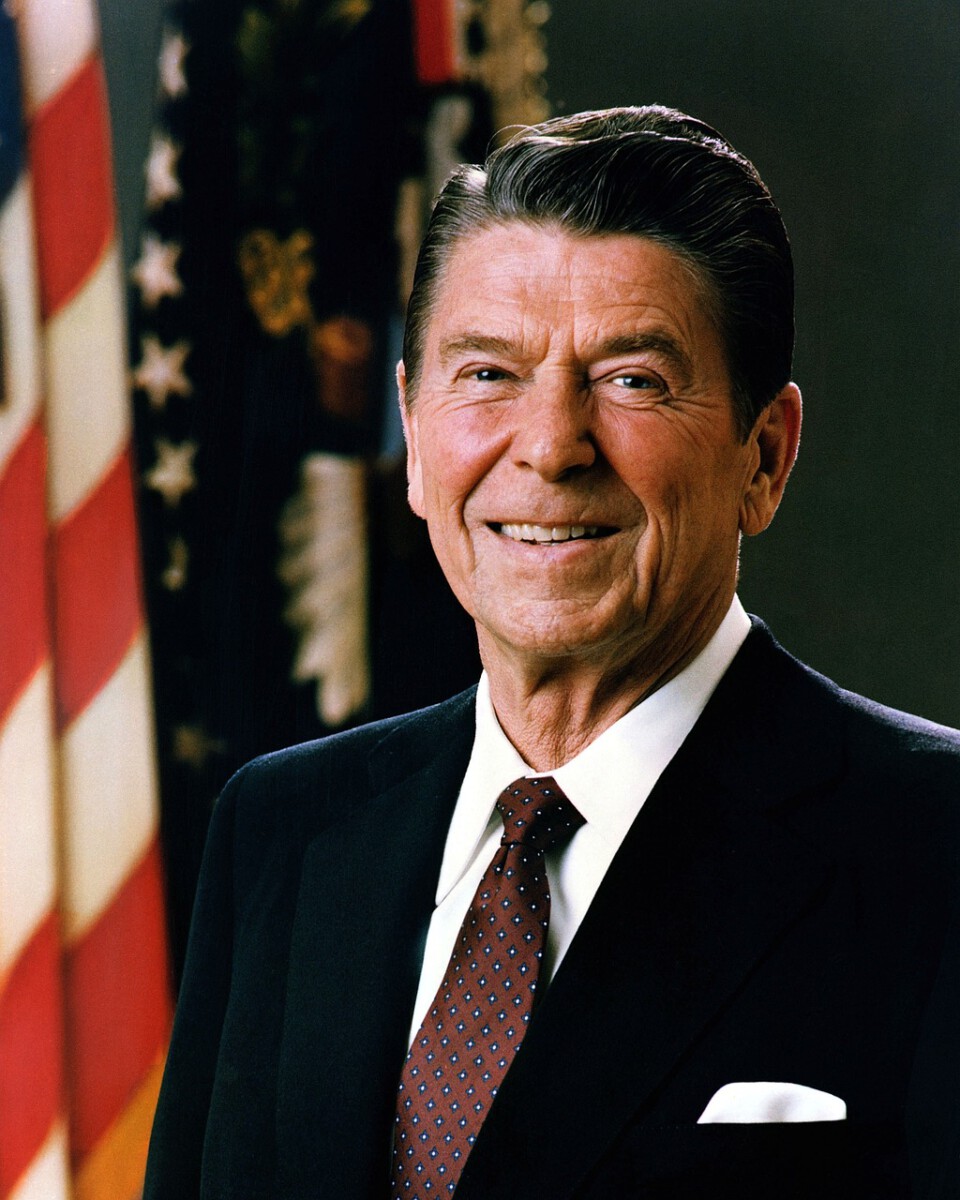

The Coalition Builder Who Changed Politics Forever

Did you know that Ronald Reagan won 49 out of 50 states in his 1984 reelection? Reagan was re-elected, receiving 58.8% of the popular vote to Mondale’s 40.6%, and winning 49 of 50 states. Reagan won a record 525 electoral votes (97.6 percent of the 538 votes in the Electoral College), the most by any candidate in American history. This stunning electoral dominance didn’t happen by accident. It was the result of Reagan’s masterful strategy to rebuild the conservative movement by uniting groups that had never worked together before. The Reagan era or the Age of Reagan is a periodization of United States history used by historians and political observers to emphasize that the conservative “Reagan Revolution” led by President Ronald Reagan in domestic and foreign policy had a lasting impact. Reagan didn’t just win elections – he redefined what it meant to be conservative in America. His approach was so successful that politicians today still invoke his name when they want to claim the mantle of authentic conservatism. Citing Reagan is nothing new for Republican presidential candidates. Before Trump’s rise in 2016, they often held up Reagan as the best example in modern times of a GOP president.

Building a New Right Coalition From Scratch

Reagan’s genius lay in bringing together three distinct groups that normally wouldn’t sit at the same political table. His victory was the result of a combination of dissatisfaction with the presidential leadership of Gerald Ford and Jimmy Carter in the 1970s and the growth of the New Right. This group of conservative Americans included many very wealthy financial supporters and emerged in the wake of the social reforms and cultural changes of the 1960s and 1970s. The first group was evangelical Christians who felt their moral values were under attack. Many were evangelical Christians, like those who joined Jerry Falwell’s Moral Majority, and opposed the legalization of abortion, the feminist movement, and sex education in public schools. The second group consisted of neoconservatives – often former Democrats who had become disillusioned with liberal foreign policy. Reagan also attracted people, often dubbed neoconservatives, who would not previously have voted for the same candidate as conservative Protestants did. Many were middle- and working-class people who resented the growth of federal and state governments, especially benefit programs, and the subsequent increase in taxes during the late 1960s and 1970s. The third group was wealthy business leaders and fiscal conservatives who wanted lower taxes and fewer regulations. Like a master chef combining unlikely ingredients, Reagan created a political recipe that would dominate American politics for decades.

The Religious Right Becomes a Political Force

Before Reagan, evangelical Christians largely stayed out of politics, believing that faith and politics shouldn’t mix. Reverend Jerry Falwell directed the full weight of the Moral Majority behind Reagan. The organization registered an estimated two million new voters in 1980. Reagan changed this by speaking their language and addressing their concerns directly. Reagan also cultivated the religious right by denouncing abortion and endorsing prayer in school. He understood that these voters weren’t just motivated by economic issues – they were driven by cultural fears. Jerry Falwell, a wildly popular TV evangelist, founded the Moral Majority in the late 1970s. Decrying the demise of the nation’s morality, the organization gained a massive following and helped to cement the status of the New Christian Right in American politics. Reagan’s ability to reassure these voters that their values mattered in American politics transformed them from a passive religious community into an active political force. It’s like watching a sleeping giant wake up and flex its muscles for the first time.

Supply-Side Economics Becomes Conservative Gospel

Reagan took a radical economic theory and made it the cornerstone of conservative thinking. His economic policies, called Reaganomics by the press, were based on a theory called supply-side economics, about which many economists were skeptical. Influenced by economist Arthur Laffer of the University of Southern California, Reagan cut income taxes for those at the top of the economic ladder, which was supposed to motivate the rich to invest in businesses, factories, and the stock market in anticipation of high returns. The idea was simple: if you cut taxes on the wealthy, they’d invest more money, creating jobs for everyone else. According to Laffer’s argument, this would eventually translate into more jobs further down the socioeconomic ladder. Economic growth would also increase the total tax revenue—even at a lower tax rate. In other words, proponents of “trickle-down economics” promised to cut taxes and balance the budget at the same time. The Reagan tax cut was huge. The top rate fell from 70 percent to 50 percent. Reagan convinced Americans that this wasn’t just about helping the rich – it was about unleashing the power of free markets to help everyone. Even though many economists disagreed, Reagan’s optimistic presentation of these ideas made them sound like common sense rather than complex economic theory.

Deregulation as Economic Freedom

Reagan transformed deregulation from a wonky policy debate into a crusade for economic freedom. But Reagan seemed less flexible when it came to deregulating industry and weakening the power of labor unions. Banks and savings and loan associations were deregulated. Pollution control was enforced less strictly by the Environmental Protection Agency, and restrictions on logging and drilling for oil on public lands were relaxed. His message was powerful: government regulations were strangling American business and preventing economic growth. Believing the free market was self-regulating, the Reagan administration had little use for labor unions, and in 1981, the president fired twelve thousand federal air traffic controllers who had gone on strike to secure better working conditions (which would also have improved the public’s safety). His action effectively destroyed the Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization (PATCO) and ushered in a new era of labor relations in which, following his example, employers simply replaced striking workers. This wasn’t just about cutting red tape – Reagan framed it as restoring American entrepreneurship and innovation. By contrast, economist Milton Friedman has pointed to the number of pages added to the Federal Register each year as evidence of Reagan’s anti-regulation presidency (the Register records the rules and regulations that federal agencies issue per year). The number of pages added to the Register each year declined sharply at the start of the Ronald Reagan presidency breaking a steady and sharp increase since 1960. He made deregulation sound like patriotism wrapped in economic policy.

The Reagan Democrats Phenomenon

Perhaps Reagan’s most impressive political achievement was convincing working-class Democrats to vote Republican. A Reagan Democrat is a traditionally Democratic voter in the United States, referring to working class residents who supported Republican presidential candidates Ronald Reagan in the 1980 and/or the 1984 United States presidential elections, and/or George H. W. Bush in the 1988 United States presidential election. The term remains part of the lexicon in American political jargon because of Reagan’s continued widespread popularity among a large segment of the electorate. These voters had been loyal Democrats for generations, but Reagan spoke to their frustrations in ways their own party didn’t. Democratic pollster Stan Greenberg issued a study of Reagan Democrats, analyzing white ethnic voters (largely unionized auto workers) in Macomb County, Michigan, just north of Detroit. The county voted 63 percent for John F. Kennedy in 1960 but 66 percent for Reagan in 1984. Reagan understood that these voters felt abandoned by a Democratic Party that seemed more interested in helping minorities and the poor than protecting middle-class jobs. He concluded that Reagan Democrats no longer saw the Democratic Party as champions of their working-class aspirations but instead saw them as working primarily for the benefit of others: the very poor, femin Reagan’s optimistic message about American strength and prosperity resonated with voters who felt their country was in decline. During the 1980 election a dramatic number of voters in the United States, disillusioned with the economic malaise of the 1970s and the presidency of Jimmy Carter (even more than four years earlier under moderate Republican Gerald Ford), supported Reagan, a former Democrat and California governor. Reagan’s optimistic tone managed to win over a broad set of voters to an almost unprecedented degree

Peace Through Strength Foreign Policy

Reagan revolutionized conservative foreign policy by combining military buildup with diplomatic engagement. The foundation of Reagan’s foreign policy, known as the Reagan Doctrine, was the support of freedom for all people around the world. His commitment to the idea of “peace through strength” led to the modernization of our military forces. His philosophy was simple: America should negotiate with enemies only from a position of overwhelming strength. Instead, Reagan believed, the Soviets had continued its drive to nuclear dominance. Since the Soviets had a huge edge in conventional warfare because of the immense size of the Red Army, Reagan and his team were concerned that they would press their own advantage throughout the world and put pressure on Western Europe to disarm. Reagan believed the buildup would show America’s traditional allies that he meant business and stiffen the spines of European anti-Communists So the buildup had three objectives: strengthening the military in case of war, persuading European allies that the United States would not abandon them, and encouraging the Soviets to come to the bargaining table. Reagan gave military spending priority over his promise of a balanced budget, telling his advisers, “Defense is not a budget issue. This wasn’t just about building more weapons – Reagan was creating psychological pressure on the Soviet Union while reassuring American allies. Think of it as diplomatic chess played with nuclear weapons.

The Star Wars Initiative That Changed Everything

Reagan’s Strategic Defense Initiative showed how he could turn science fiction into political reality. The Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI), derisively nicknamed the “Star Wars” program, was a proposed missile defense system intended to protect the United States from attack by ballistic nuclear missiles. The program was announced in 1983, by President Ronald Reagan. Reagan called for a system that would render nuclear weapons obsolete, and to end the doctrine of mutual assured destruction (MAD), which he described as a “suicide pact”. Critics mocked the program as impossible to build and potentially destabilizing to nuclear balance. They dismissed the idea of a technical solution to the Cold War, saying that a defense shield could be viewed as threatening because it would inhibit Soviet offensive capabilities while leaving America’s offense intact. But Reagan understood that the mere possibility of SDI would force the Soviets to spend resources they didn’t have. They commonly expressed the notion that SDI was equivalent to starting an economic war through a defensive arms race to further cripple the Soviet economy with extra military spending. Another common Soviet perception suggested that SDI served as a disguise for a US desire to initiate a first strike on the Soviet Union. Whether SDI ever worked didn’t matter – the threat of it working was enough to change the entire Cold War dynamic. While SDI was not directly included in the treaty text, many observers have argued that the pressure exerted by SDI research and development efforts encouraged the Soviets to come to the negotiating table. SDI also forced the Soviet Union to rethink its military posture.

The Great Communicator’s Secret Weapon

Reagan’s communication skills weren’t just about being charming on television – they were strategic tools for building conservative consensus. Reagan was an articulate spokesman for his political perspectives and was able to garner support for his policies. Often called “The Great Communicator,” he was noted for his ability, honed through years as an actor and spokesperson, to convey a mixture of folksy wisdom, empathy, and concern while taking humorous digs at his opponents. He had this uncanny ability to explain complex conservative ideas in simple terms that regular people could understand. Indeed, listening to Reagan speak often felt like hearing a favorite uncle recall stories about the “good old days” before big government, expensive social programs, and greedy politicians destroyed the country. Americans found this rhetorical style extremely compelling. Reagan understood that most Americans don’t want to hear lectures about economic theory or foreign policy – they want to hear stories about how policies will make their lives better. Reagan and other conservatives successfully presented conservative ideas as an alternative to a public that had grown disillusioned with New Deal liberalism. Reagan’s charisma and speaking skills helped him frame conservatism as an optimistic, forward-looking vision for the country. He turned conservative ideology from something that sounded angry and backward-looking into something that sounded hopeful and patriotic. It’s like watching a master salesman convince you that what you really need is exactly what he’s selling.

Government as the Problem, Not the Solution

Reagan’s most famous line redefined how Americans thought about their own government. After noting the severity of the nation’s economic crisis, Reagan declared that “government is not the solution to our problem; government is the problem.” He took pains to reassure Americans that he did not want to “do away with government.” Rather, he sought “to make it work—work with us, not over us; to stand by our side, not ride on our back.” This wasn’t just political rhetoric – it was a fundamental shift in conservative thinking about the role of government in American life. In his first inaugural address Reagan proclaimed that “government is not the solution to the problem, government is the problem.” In reality, Reagan focused less on eliminating government than on redirecting government to serve new ends. In line with that goal, his administration embraced supply-side economic theories that had recently gained popularity among the New Right. Reagan convinced Americans that the federal government had grown too big and too intrusive, taking money from hardworking citizens and giving it to people who didn’t deserve it. If these policies were to be enacted, Reagan promised that they would mark the “beginning of the end of inflation.” A central tenet to Reagan’s campaign was his belief that the federal government had grown too far beyond the implied parameters of the Constitution. He had held these beliefs since his earliest foray into politics in the 1960s, but the nationwide crises and incidents of corruption through the ensuing decades increased public belief in Reagan’s views on smaller government. This message resonated with voters who felt that government had become disconnected from their daily struggles and more interested in social engineering than practical problem-solving.

Electoral Dominance That Proved the Strategy Worked

The proof of Reagan’s strategic genius lies in the numbers: he didn’t just win elections, he dominated them. On election day, Reagan overwhelmed Carter, winning 51 percent of the vote to Carter’s 41 percent. Anderson had less than 7 percent of the vote but siphoned support from Carter in states such as New York and Massachusetts, enabling Reagan to carry these states and win an electoral landslide. Reagan won 489 electoral votes to Carter’s 49. But his 1984 reelection was even more impressive. The Reagan-Bush ticket won an overwhelming victory on election day, carrying every state but Mondale’s Minnesota and the District of Columbia, and defeating Mondale in the Electoral College by 525 to 13. Reagan’s popular vote total was even more impressive—54 million votes to Mondale’s 37 million—a margin exceeded only by Nixon’s win over George McGovern in 1972. Reagan’s coalition was so broad that he won across demographic lines that Republicans had never captured before. Reagan won a majority of independents and more than a fifth of the Democratic vote. He ran more strongly among the youngest cohort of voters than any Republican in the twentieth century. Traditional Republican support among white Protestants, small-town and rural Americans, college graduates, upper-class Americans, and white-collar managers and professionals remained exceedingly strong. Reagan won virtually every demographic group except African Americans. His margin of victory over Mondale was nearly 17 million popular votes, the second largest in history; it was surpassed only by Richard Nixon’s margin over McGovern in 1972.