Political Polarization Mirrors Civil War Battle Lines

The electoral map of America today looks strikingly similar to the divisions that tore the nation apart in 1861. At this stage, Biden is judged by the highly respected Cook Political Report to have 226 out of the necessary 270 votes in the electoral college, with the majority (116) coming from former Union states. Trump has 235 votes, with a majority (135) coming from former states in the Confederacy. The continuing legacy of the civil war remains. This geographic persistence isn’t just political theater – it reveals how deeply the Civil War carved permanent channels in America’s political landscape.

The US is now more divided along ideological and political lines than at any time since the 1850s. These divisions echo through modern American politics like a haunting melody that refuses to fade. An increasingly Balkanized US is likely to be even more inward-looking, preoccupied with internal divisions over immigration, race, inequality, and sexual and gender identity issues.

Racial Identity Shapes Party Allegiance

If you look at the Republican Party, up until this last election in 2024, it was over 80% white. This isn’t just a number – it’s a stark reminder of how the Civil War’s racial divisions continue to define American politics. And that is in a country that’s multiethnic, multi-religious, multiracial. So our parties are more ethnically, religiously, racially based than would make sense if you look strictly based on ideology.

The flip side tells an equally revealing story. On the other side of the ledger, if you look at the Democratic Party, the overwhelming majority of African Americans, a majority of Latinos, the majority of Asians, a majority of Muslims and Jews vote for the Democratic Party. These patterns aren’t accidents of political history – they’re the direct descendants of the choices made during and after the Civil War.

The Myth of a Lost Cause Lives On

Post-war, there was a concerted effort to reinterpret and teach the war’s causes and consequences, with some narratives, especially in the South, pushing the “Lost Cause” myth. This myth romanticized the Confederate cause, portraying it as a noble but doomed struggle against overwhelming odds, conveniently downplaying or ignoring the central role of slavery in the conflict.

The Lost Cause narrative didn’t die with the Confederate veterans. It evolved, adapting to new generations while maintaining its core mission of reshaping how Americans remember their bloodiest conflict. Nearly half of self-described Southern whites (49%) see states’ rights as the war’s main cause; among whites who do not consider themselves Southerners, a comparable percentage (48%) also says states’ rights was the war’s main cause. However, self-described Southern whites are more likely than other whites to view praise by politicians for Confederate leaders as appropriate and to have a positive reaction to displays of the Confederate flag.

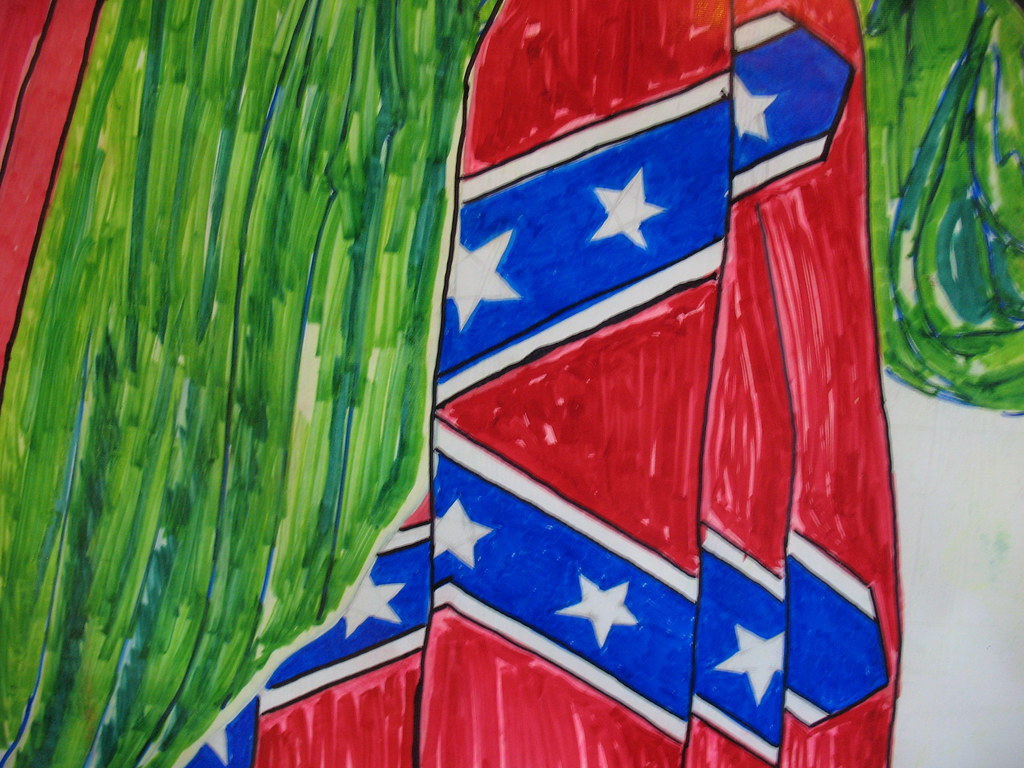

Confederate Symbols as Modern Battlefields

Drive through the American South today and you’ll still see Confederate flags flying from pickup trucks and front porches. These aren’t just nostalgic decorations – they’re active statements about identity and belonging. In a roundtable moderated by Adam Domby and Karen L. Cox, eight scholars and history practitioners discuss contemporary debates and protests over Confederate monuments, their removal, and their place in Civil War memory.

The fights over Confederate monuments that erupted nationwide in recent years revealed how the Civil War’s ghosts still walk among us. When cities remove statues of Confederate generals, they’re not just changing decorations – they’re wrestling with fundamental questions about who belongs in America’s story and which version of the past we choose to honor.

Educational Systems as Ideological Battlegrounds

Educational institutions and curricula were not untouched by the war’s impact. Universities, especially in the South, grappled with financial challenges and loss of students. But the deeper impact wasn’t financial – it was ideological. The way America teaches its children about the Civil War shapes how they understand themselves as Americans.

Modern battles over curriculum echo these Civil War divisions. When school boards debate how to teach about slavery, segregation, and civil rights, they’re fighting the same fundamental battle that defined the 1860s: what kind of country is America, and who gets to decide? Organizations like the United States Sanitary Commission saw significant female participation, as women organized fundraisers, cared for the wounded, and pr – these forgotten stories of Civil War activism continue to inspire modern movements for justice and equality.

Violence as Political Expression

The people who tend to initiate violence are the people who once had a lot of status and privilege, who had once been dominant in that country politically and economically, but who understand or they see themselves in decline. They are losing status. And what happens in those situations is they create this myth, this myth that they are the founders of the country, that they deserve to rule, that the identity of the country is based on their identity.

This pattern of political violence rooted in perceived status loss echoes through American history from Reconstruction to January 6th. A Department of Homeland Security document reported by Politico last year warned of an uptick of extremists discussing a civil war: “Some domestic violent extremists (DVEs) are reacting to the 2024 election season and prominent policy issues by engaging in illegal preparatory or violent activity that they link to the narrative of an impending civil war, raising the risk of violence against government targets and ideological opponents.”

Federal Versus State Power Tensions

The Civil War was fundamentally a fight about whether states could defy federal authority. That same tension persists today in countless forms, from immigration policy to gun control to pandemic responses. Moreover, these civil war era divisions have now emerged in a constitutional confrontation over immigration. In January, the US Supreme Court ordered Texas to remove razor wire it had put up along the Rio Grande river to stop migrants from crossing. Texas Governor Greg Abbot refused to comply, claiming the compact between the states and the United States had been broken by President Biden’s failure to halt illegal immigration.

When governors openly defy federal authority today, they’re not just making policy statements – they’re invoking the same constitutional arguments that led to secession in 1861. The weapons may be legal briefs instead of muskets, but the underlying conflict remains the same.

Economic Inequality Reflects Historical Divisions

Before the Civil War, the agrarian South felt economically disadvantaged compared to the industrializing North. Now, inequality and perceived neglect of rural areas by the urban policies further this resentment. The economic fault lines that helped cause the Civil War have shifted but never healed.

Rural America’s sense of abandonment by coastal elites mirrors the South’s antebellum resentment of Northern industrial power. When farmers in Iowa or factory workers in Ohio feel forgotten by Washington, they’re experiencing an echo of the same economic tensions that helped tear the nation apart in 1861. These aren’t just policy disagreements – they’re fights about which vision of America deserves to prosper.

Social Media Amplifies Historical Divisions

I think the single easiest and most immediate thing that we could do, and also the cheapest — for everybody except maybe a few tech moguls — is to regulate social media. The five biggest tech companies in the world are all American companies, and they are essentially unregulated. Social media doesn’t create America’s divisions, but it supercharges them with the same inflammatory power that newspapers wielded in the 1850s.

In the 1860s, newspapers and pamphlets fueled the fire, spreading partisan views and exaggerating the issues. Today’s Facebook posts and Twitter battles serve the same function as yesterday’s inflammatory editorials and partisan pamphlets. The technology has evolved, but the human tendency to retreat into ideological bubbles remains depressingly constant.

Geographic Sorting Deepens Cultural Divides

A modern American civil war would not resemble the geographic simplicity of North versus South. Instead, it would be a fragmented, chaotic, and deeply internalized conflict that would devastate communities from within. Unlike 1861, when battle lines followed state borders, today’s divisions run through neighborhoods, families, and friend groups.

The electoral map, at least from the most recent presidential election, does show blue coasts and a red middle. But I think that’s also a deceptive picture since we know that in many states, such as Florida, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, Michigan, there are deep internal divisions. This geographic sorting makes modern divisions both more intimate and more dangerous than the cleaner regional splits of the 1860s.

Religious and Cultural Identity Politics

The Civil War transformed American Christianity, splitting denominations along regional lines that persist today. Southern Baptists and Northern Methodists created separate churches that reflected their different views on slavery and federal authority. These religious divisions continue to shape American politics, with white evangelical Protestants forming a crucial Republican voting bloc while Black Protestants overwhelmingly support Democrats.

Of the 21 states with the most permissive gun laws in 2023, 19 voted for Trump, and six were in the Confederacy. Of the 19 states that enacted laws in 2022 making it harder to vote, 14 voted for Trump and seven were in the Confederacy. And of the 23 states that enacted legislation in 2023 imposing restrictions on gender-affirming care, transgender participation in school sports, school instruction touching on LBGTQ issues and related matters, 22 voted for Trump and nine were in the Confederacy. These modern culture war battles follow the same geographic and ideological lines carved by the Civil War.

Institutional Memory and Collective Trauma

For the African American community, the war and subsequent Reconstruction represented a period of hope and tumultuous change. The promise of equality, though enshrined in constitutional amendments, was constantly challenged by white supremacy. However, the war did facilitate the emergence of African American leaders, both in politics and community spheres. Institutions, primarily churches and schools, became centers of empowerment and played pivotal roles in the struggle for civil rights.

The Civil War created institutional memories that continue to shape how different communities understand their place in America. Black churches that formed during Reconstruction still anchor communities today. Historically Black colleges and universities trace their origins to the post-war period. These institutions carry forward not just educational missions, but collective memories of struggle, resistance, and hope that define African American identity.

International Implications of Internal Division

America’s friends and allies need to understand that the United States has become a Disunited States. There are effectively two Americas – and they are at war. They are fighting over social, political and constitutional issues, and over what role the US should play in the world. America’s internal divisions don’t just affect Americans – they reshape global politics and international relations.

When America seems unable to govern itself effectively, its allies question whether they can depend on American leadership. The Civil War left an indelible mark on American military strategy and foreign policy. While the immediate repercussions were evident in the war’s tactics and technologies, the longer-term effects are discerned in how America approached conflicts and its position on the global stage. Today’s internal divisions continue this pattern, making America a less reliable international partner.

The Persistence of Civil War Mentality

Just as southerners never fully accepted the outcome of the civil war, Trump supporters who believe the 2020 election was stolen are unlikely to gracefully accept a loss in 2024, presaging more resentment and possible renewed violence. The Civil War never truly ended – it just changed forms. The same mentality that refused to accept defeat in 1865 persists in those who refuse to accept electoral defeat today.

Only 6.5% of respondents strongly or very strongly agreed that civil war was likely in the near future, and just 3.6% agreed that such a conflict was needed. While most Americans don’t expect another civil war, the very fact that millions of people consider it possible reveals how the original conflict’s wounds never fully healed. The Civil War’s greatest impact on American identity may be this: it proved that the United States could break apart, and that knowledge has haunted the national psyche ever since.

The Civil War didn’t just end slavery and preserve the Union – it fundamentally rewired how Americans think about themselves, their government, and each other. From voting patterns to cultural conflicts, from religious divisions to economic resentments, the war’s fingerprints are everywhere in modern America. Understanding these connections isn’t just academic exercise – it’s essential for anyone trying to make sense of why a nation founded on unity remains so deeply, persistently divided. Can a country ever fully heal from wounds this deep, or are we destined to keep fighting the same battles in new forms?