A Preacher’s Divine Mission

In the early hours of a sweltering Virginia morning, something unthinkable was about to happen. On the evening of August 21–22, 1831, an enslaved preacher and self-styled prophet named Nat Turner launched the most deadly slave revolt in the history of the United States. Over the course of a day in Southampton County, Turner and his allies killed fifty-five white men, women, and children as the rebels made their way toward Jerusalem, now known as Courtland. A deeply religious person, Nat Turner believed that he had been called by God to lead African Americans out of slavery. What started as whispered prayers in hidden gatherings would become the bloodiest uprising that would shake the very foundations of Southern society. His mother was an African native who transmitted a passionate hatred of slavery to her son.

Signs in the Heavens

Beginning in February 1831, Turner interpreted atmospheric conditions as signs to prepare for the revolt. An annular solar eclipse on February 12, 1831, was visible in Virginia and much of the southeastern United States; Turner envisioned this as a Black man’s hand reaching over the sun. The enslaved preacher had been waiting for divine confirmation, and nature seemed to provide it repeatedly. On August 13, an atmospheric disturbance made the Virginia sun appear bluish-green, possibly the result of a volcanic plume produced by the eruption of Ferdinandea Island off the coast of Sicily. In 1831, shortly after he had been sold again—this time to a craftsman named Joseph Travis—a sign in the form of an eclipse of the Sun caused Turner to believe that the hour to strike was near. For Turner, these weren’t just natural phenomena but direct messages from God.

The Inner Circle Forms

Turner said, “I communicated the great work laid out to do, to four in whom I had the greatest confidence”: fellow slaves Henry, Hark, Nelson, and Sam. These men would become the core conspirators in what would unfold as America’s most devastating slave rebellion. In February 1831, four slaves in Southampton County, Virginia, went to a clandestine meeting called by an enslaved preacher named Nat Turner. When they got there, Turner told them the time had come to launch a slave revolt. All agreed. The planning was meticulous yet shrouded in secrecy. Songs may have tipped the neighborhood members to movements: “It is believed that one of the ways Turner summoned fellow conspirators to the woods was through the use of particular songs.”

The False Start That Saved Lives

Over the next few months, the conspirators planned to launch the revolt on the Fourth of July, a date that implicitly invoked Thomas Jefferson’s claim that “all men are created equal.” As the day approached, however, Nat Turner fell ill. Independence Day passed without any noticeable unrest among the slaves. This delay would prove crucial, as it allowed Turner’s followers to refine their plans and recruit additional members. Illness prevented Turner from starting the rebellion as planned on Independence Day, July 4, 1831. The conspirators used the delay to extend planning. Sometimes fate intervenes in history’s most violent moments, and Turner’s illness may have prevented an even bloodier outcome.

The Night Terror Begins

An insurrection was planned, aborted, and rescheduled for August 21,1831, when he and six others killed the Travis family, managed to secure arms and horses, and enlisted about 75 other enslaved people in a large but disorganized insurrection that resulted in the murder of an estimated 55 white people. The rebellion began at the Travis household where Turner was enslaved. On August 21, 1831, at 2:00 a.m., Turner and his followers started at his master’s house and killed the entire family. Their plan was to move systematically from plantation to plantation in Southampton and kill all white people connected to slavery, including men, women, and children. They started on their own plantation and murdered Turner’s owner and his family. During the next twenty-four hours, Turner and his fellow insurgents moved throughout the county to eleven different plantations, killing fifty-five people and inspiring fifty or sixty enslaved men to join their ranks.

A Kingdom of Fear Spreads

There was widespread fear among the White population in the rebellion’s aftermath. Militias and mobs killed as many as 120 enslaved people and free African Americans in retaliation. News of the uprising spread like wildfire across Virginia and into neighboring states. Whites from southern Virginia and parts of North Carolina regained control of Southampton within two days, but immediately after the revolt, whites throughout the country were on edge. The images from Nat Turner’s Rebellion — of armed black men roaming the country side slaying white men, women, and children — haunted white southerners and showed slave owners how vulnerable they were. The unthinkable had happened, and Southern society would never feel secure again.

The Brutal Response

Even though Turner and his followers had been stopped, panic spread across the region. In the days following the attack, 3000 soldiers, militia men, and vigilantes killed more than one hundred suspected rebels. The white retaliation was swift and merciless. One newspaper editor who had travelled to Southampton County admitted that the white retribution was “hardly inferior in barbarity to the atrocities of the rebels.” Whites also reported using torture. In addition, to terrorize the local African American population, some of the militia decapitated about fifteen of the captured insurgents and put their heads on stakes. Then, as fear spread through the white population, white mobs turned on blacks who had played no role in the uprising. An estimated two to three hundred African Americans, most of whom were not connected to the rebellion, were murdered by white mobs.

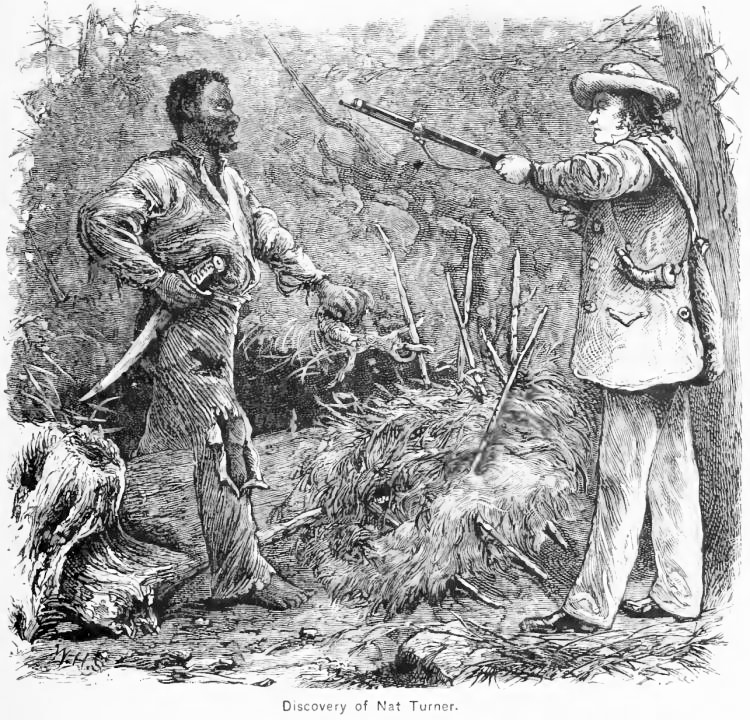

The Prophet in Hiding

The rebellion was effectively suppressed within a few days, at Belmont Plantation on the morning of August 23, but Turner survived in hiding for more than 30 days afterward. While his followers were captured or killed, Turner managed something extraordinary – he disappeared. Turner himself eluded capture throughout September and into October, when two enslaved men spotted him close to where the revolt began. Once detected, Turner was forced to move and was unable to elude the renewed manhunt. He was captured on October 30. On October 30, Benjamin Phipps, a farmer, discovered Turner hiding in Southampton County in a depression in the earth created by a large, fallen tree covered with fence rails. His ability to remain free for over two months only added to the legend.

Confessions of a Revolutionary

While in jail awaiting trial, Turner spoke freely about the revolt. Local lawyer Thomas R. Gray approached Turner with a plan to take down his confessions. The Confessions of Nat Turner was published within weeks of the Turner’s execution on November 11, 1831, and remains an important source for historians. Gray’s account would become the primary historical document about Turner, though modern scholars question its authenticity. Thomas Gray, a lawyer, released the account, claiming that Turner had dictated the confessions to him and that there was little to no variation from the prisoner’s actual testimony. However, as a slaveholder mired in financial difficulty, Gray likely saw tremendous profit and propaganda potential in satiating the public’s thirst for knowledge about such an enigmatic figure. Turner was tried on November 5, 1831, for “conspiring to rebel and making insurrection”, and was convicted and sentenced to death. Turner was hanged on November 11, 1831, in the county seat of Jerusalem, Virginia (now Courtland).

The Macabre Aftermath

According to some sources, he was beheaded to deter further rebellion. The body was dissected and flayed, and the skin used to make souvenir purses. In October 1897, Virginia newspapers reported that Dr. H. U. Stephenson of Toano, Virginia, was using the skeleton as a medical specimen. The treatment of Turner’s body after death reveals the depth of white fear and rage. Southern society wasn’t content with simply executing Turner – they needed to obliterate him entirely. Thirty enslaved persons and one free black were convicted, but a dozen of them escaped the gallows when the governor, following the recommendation of the court, commuted the sentences of those who had contributed little to the rebels’ cause. Others had their sentence commuted because they were young or reluctant rebels. Even in death, Turner’s influence continued to terrify those who had enslaved him.

The Great Tightening

Nat Turner’s rebellion led to the passage of a series of new laws. The Virginia legislature actually debated ending slavery, but chose instead to impose additional restrictions and harsher penalties on the activities of both enslaved and free African Americans. Other slaveholding states followed suit, restricting the rights of free and enslaved Black people to gather in groups, travel, preach, and learn to read and write. The rebellion had the opposite effect that Turner intended. Because the revolt reminded whites about the dangers of slavery, approximately two thousand Virginians petitioned their legislature to do something to end the practice. Thomas Jefferson’s grandson, Thomas Jefferson Randolph, introduced a gradual emancipation bill that failed by a narrow margin. It was the last time Virginia would consider a proposal to gradually eliminate slavery until after the end of the Civil War. This moment represented the South’s final opportunity to voluntarily abandon slavery.

The Echoes of Revolution

Nat Turner’s rebellion was one of the bloodiest and most effective in American history. It ignited a culture of fear in Virginia that eventually spread to the rest of the South, and is said to have expedited the coming of the Civil War. Turner’s rebellion didn’t occur in isolation – it was part of a broader age of revolution. Despite the surface appearance of calm, however, slavery was becoming an increasingly intractable problem in an age of revolution. Slave rebels had used the ideology of American and French revolutionaries in creating a second republic in the new world, Haiti. National Museum of African American History and Culture director Lonnie Bunch said, “The Nat Turner rebellion is probably the most significant uprising in American history.” The rebellion shattered the illusion that enslaved people were content with their bondage and exposed the violent reality at the heart of American slavery.

Conclusion

Turner’s rebellion stands as a watershed moment in American history, forever changing how both North and South viewed slavery. Nat Turner’s rebellion put an end to the white Southern myth that slaves were either contented with their lot or too servile to mount an armed revolt. The uprising terrified the South not just because of its violence, but because it revealed the fundamental instability of a system built on human bondage. While Turner failed to spark the general uprising he had envisioned, his rebellion accelerated the nation’s march toward the Civil War and demonstrated that enslaved people would risk everything for freedom. The rebellion that lasted barely two days created ripples that would be felt for decades to come. What would you have risked for freedom?