South Carolina’s Revolutionary Defiance Against Federal Authority

South Carolina stands alone in American history as the only state bold enough to attempt secession from the Union not once, but twice. This remarkable distinction emerged from deep-seated tensions over states’ rights, economic policies, and federal overreach that would define the state’s political identity for generations. The first attempt came during the Nullification Crisis of 1832-33, when South Carolina declared federal tariffs null and void within its borders. The second, more famous attempt occurred in 1860, when the state became the first to secede from the Union, triggering the Civil War. These twin acts of defiance weren’t mere political theater—they represented fundamental disagreements about the nature of American federalism that continue to resonate today.

The Nullification Crisis: Testing Federal Authority in 1832

The roots of South Carolina’s first secession attempt trace back to the Tariff of 1828, dubbed the “Tariff of Abominations” by its critics. This protective tariff imposed heavy duties on imported goods, benefiting Northern manufacturers while devastating the Southern economy that relied heavily on imported goods and agricultural exports. South Carolina’s economy, built on cotton production and slave labor, suffered disproportionately as the tariff made imported goods prohibitively expensive while reducing demand for Southern cotton in international markets. Vice President John C. Calhoun, a South Carolina native, secretly authored the South Carolina Exposition and Protest, arguing that states had the constitutional right to nullify federal laws they deemed unconstitutional. The document laid the theoretical groundwork for what would become known as the doctrine of nullification, challenging the supremacy of federal law over state authority.

The Ordinance of Nullification: South Carolina’s Bold Declaration

In November 1832, South Carolina took unprecedented action by calling a special state convention that passed the Ordinance of Nullification. This document declared the federal tariffs of 1828 and 1832 “null, void, and no law” within South Carolina’s borders, effective February 1, 1833. The ordinance went further, prohibiting federal officers from collecting tariff duties in South Carolina ports and threatening secession if the federal government attempted to use force. State officials were required to take an oath supporting nullification, and the legislature authorized the raising of a military force to resist federal authority. The audacious move represented the most serious challenge to federal authority since the founding of the republic, setting a dangerous precedent that would echo through American history.

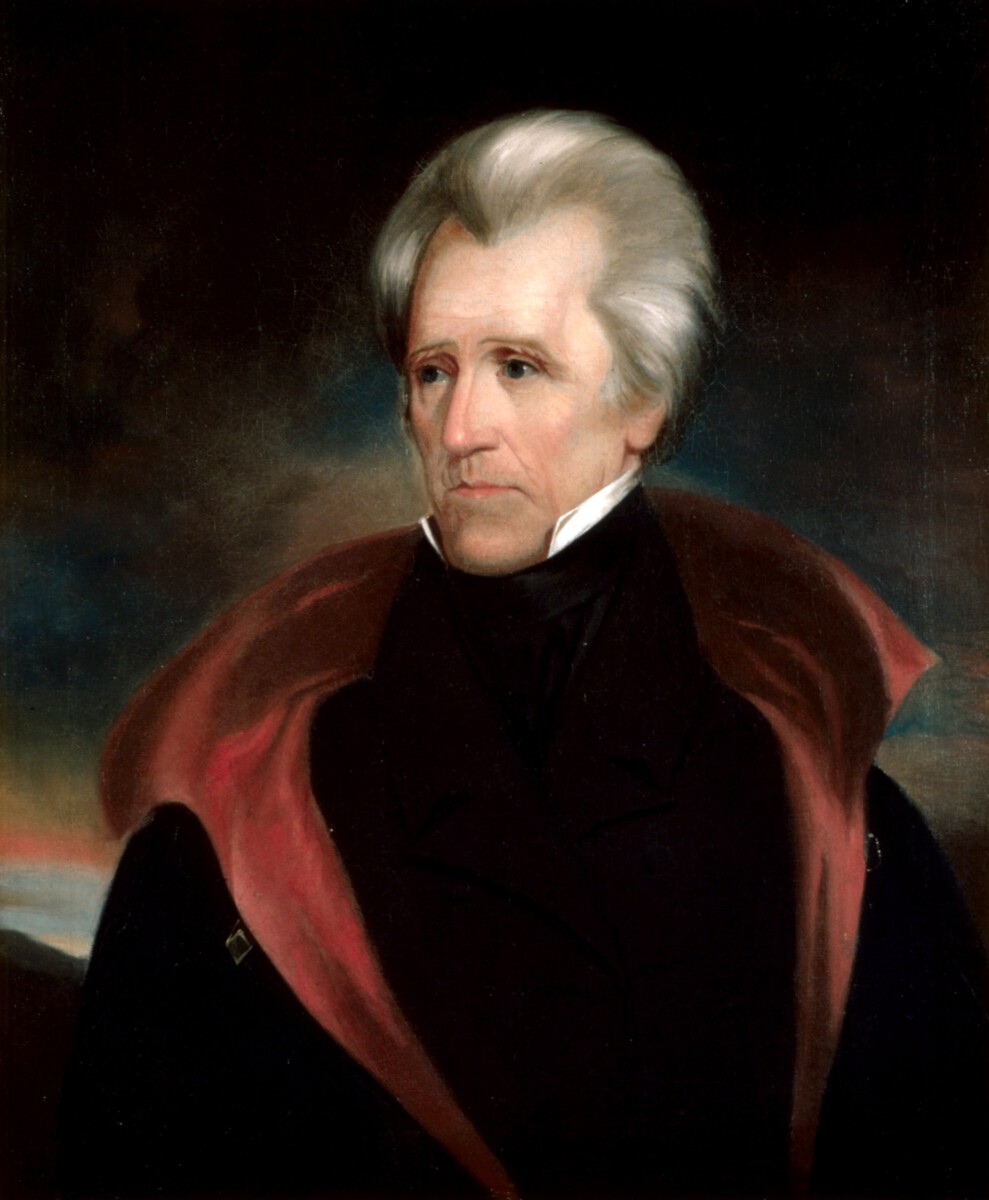

President Jackson’s Iron-Fisted Response

President Andrew Jackson, despite being a fellow Southerner and advocate for states’ rights, viewed South Carolina’s actions as treasonous and responded with characteristic force. In December 1832, Jackson issued his Proclamation to the People of South Carolina, declaring nullification incompatible with the Constitution and warning that “disunion by armed force is treason.” The president began moving federal troops to Charleston and reinforcing federal forts, while Congress considered the Force Bill, which would authorize military action to collect tariffs. Jackson’s private correspondence revealed his determination to preserve the Union at all costs, reportedly stating he would hang Calhoun and other nullification leaders if necessary. The crisis reached a fever pitch as both sides prepared for potential armed conflict, with South Carolina mobilizing its militia and the federal government positioning warships off Charleston harbor.

Henry Clay’s Compromise Prevents Bloodshed

As tensions reached a breaking point, Senator Henry Clay of Kentucky stepped forward with a compromise tariff that would gradually reduce rates over the next decade. The Compromise Tariff of 1833 provided South Carolina with enough face-saving concessions to back down from its confrontational stance while preserving federal authority. Congress passed both Clay’s compromise tariff and the Force Bill simultaneously in March 1833, giving Jackson the tools he needed while offering South Carolina a peaceful resolution. The state convention reconvened and repealed the Ordinance of Nullification, though it symbolically nullified the Force Bill as a final act of defiance. This delicate balance prevented the first secession crisis from escalating into armed conflict, but the underlying constitutional questions remained unresolved.

The Seeds of Future Conflict: 1833-1860

The nullification crisis established dangerous precedents that would resurface with devastating consequences nearly three decades later. South Carolina’s actions demonstrated that a determined state could challenge federal authority and potentially extract concessions through threats of secession. The episode elevated John C. Calhoun to national prominence as the intellectual architect of states’ rights theory, and his ideas continued to influence Southern political thought throughout the antebellum period. Meanwhile, the compromise solution satisfied neither extreme faction—radical nullifiers felt betrayed by the backing down, while strong unionists worried about rewarding defiance with concessions. The unresolved tensions over federal versus state authority, along with the growing sectional divide over slavery, created a powder keg that would eventually explode in 1860.

The Election of 1860: The Final Straw

Abraham Lincoln’s election to the presidency in November 1860 triggered South Carolina’s second and more consequential secession attempt. Despite receiving less than forty percent of the popular vote nationally and not appearing on ballots in most Southern states, Lincoln’s victory represented an existential threat to South Carolina’s plantation economy and way of life. The Republican Party’s platform opposed the expansion of slavery into new territories, which Southern leaders viewed as the first step toward abolition. Within days of Lincoln’s election, South Carolina’s legislature called for a secession convention, and prominent politicians began openly advocating for immediate separation from the Union. The state’s newspapers, political leaders, and wealthy planters united behind secession with an enthusiasm that dwarfed the nullification crisis, viewing Lincoln’s election as proof that the South could no longer protect its interests within the federal system.

December 20, 1860: The Fateful Declaration

On December 20, 1860, delegates at St. Andrew’s Hall in Charleston unanimously passed the Ordinance of Secession, declaring that “the union now subsisting between South Carolina and other states, under the name of the United States of America, is hereby dissolved.” The announcement triggered wild celebrations throughout Charleston, with church bells ringing, cannons firing, and crowds gathering in the streets to celebrate what they saw as a second declaration of independence. Unlike the nullification crisis, this time South Carolina had no intention of backing down or seeking compromise—the decision was final and irrevocable. The secession ordinance cited the election of a president “whose opinions and purposes are hostile to slavery” as justification for the break, along with Northern states’ failure to return fugitive slaves and their opposition to slavery’s expansion. Within weeks, six other Deep South states would follow South Carolina’s lead, creating the Confederate States of America.

The Economic Motivations Behind Secession

South Carolina’s decision to secede was driven primarily by economic concerns related to the state’s dependence on slave labor and cotton production. By 1860, enslaved people comprised nearly sixty percent of South Carolina’s population, representing millions of dollars in invested capital that would be worthless if slavery were abolished. The state’s economy was entirely built around large plantations producing cotton, rice, and other cash crops for export, with Charleston serving as a major port for the international slave trade until 1808. Wealthy planters who dominated South Carolina politics understood that Republican policies would eventually strangle their economic system, making secession a matter of financial survival rather than abstract constitutional principles. The state’s leaders calculated that independence would allow them to expand slavery into new territories, maintain their labor system indefinitely, and potentially reopen the international slave trade.

Fort Sumter: Where Secession Led to War

South Carolina’s secession directly precipitated the Civil War when Confederate forces fired on Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor on April 12, 1861. The fort, still occupied by federal troops under Major Robert Anderson, became a symbol of federal authority that the new Confederate government could not tolerate. Months of tense negotiations between Confederate officials and the incoming Lincoln administration failed to resolve the standoff, with South Carolina demanding the evacuation of all federal forces from its territory. When Lincoln attempted to resupply the fort with provisions, Confederate batteries opened fire, beginning the bombardment that would last thirty-four hours and mark the official start of the Civil War. The attack on Fort Sumter transformed South Carolina’s act of political defiance into armed rebellion, drawing the entire nation into a conflict that would cost over 600,000 lives and reshape American society forever.

The Aftermath: Reconstruction and Federal Occupation

South Carolina’s second secession attempt ended in catastrophic defeat, with the state suffering devastating consequences during and after the Civil War. General William Tecumseh Sherman’s march through South Carolina in 1865 brought widespread destruction, with Columbia burned and Charleston severely damaged by Union forces. The state lost roughly twelve percent of its white male population during the war, while the emancipation of nearly 400,000 enslaved people destroyed the economic foundation of the plantation system. During Reconstruction from 1865 to 1877, South Carolina was occupied by federal troops and governed by Republican administrations that included newly freed slaves and Northern carpetbaggers. The state’s political and economic elite found themselves stripped of power and facing a social revolution that overturned centuries of racial hierarchy, making secession’s ultimate outcome the opposite of what its architects had intended.

The Constitutional Legacy of South Carolina’s Defiance

South Carolina’s two attempts at secession established important precedents in American constitutional law and political theory that continue to influence debates about federal versus state authority. The nullification crisis helped define the limits of state resistance to federal law, while the Civil War settled the question of secession’s legality through force of arms rather than constitutional interpretation. The Supreme Court’s 1869 decision in Texas v. White formally declared secession unconstitutional, ruling that the Constitution created an “indestructible Union” of “indestructible States.” However, South Carolina’s actions contributed to ongoing discussions about states’ rights, federal overreach, and the proper balance of power in the American system. Modern political movements occasionally invoke nullification theory when challenging federal mandates, though none have approached the level of direct confrontation that South Carolina attempted in 1832 and 1860.

South Carolina’s Unique Place in American History

No other state in American history has matched South Carolina’s willingness to directly challenge federal authority through threats of secession, making it a unique case study in American political development. The state’s actions reflected the particular economic and social circumstances of a plantation society built on slave labor, but they also revealed broader tensions within the federal system that persist today. South Carolina’s leadership class demonstrated both remarkable political courage and catastrophic judgment, willing to risk everything to preserve their way of life but ultimately destroying it through their defiance. The state’s two secession attempts bookended a crucial period in American history, from the early tests of federal authority in the 1830s to the ultimate crisis of the Union in the 1860s. These episodes remind us that the American experiment in democratic federalism has never been guaranteed, requiring constant vigilance and compromise to maintain the delicate balance between state and federal power that defines our constitutional system.

Lessons from the Palmetto State’s Rebellion

South Carolina’s double attempt at secession offers enduring lessons about the dangers of political extremism and the importance of constitutional compromise in maintaining democratic institutions. The state’s experience demonstrates how economic interests can drive political radicalism, leading rational actors to make catastrophic decisions when they perceive existential threats to their way of life. The nullification crisis showed that determined resistance could extract concessions from the federal government, but the Civil War proved that some principles—like the preservation of the Union—were non-negotiable. Modern Americans can learn from South Carolina’s example about the importance of working within the constitutional system rather than attempting to destroy it when political outcomes prove unfavorable. The state that tried to secede twice ultimately discovered that the bonds of Union, though sometimes strained, proved stronger than the forces trying to break them apart.