The Myth That Started It All

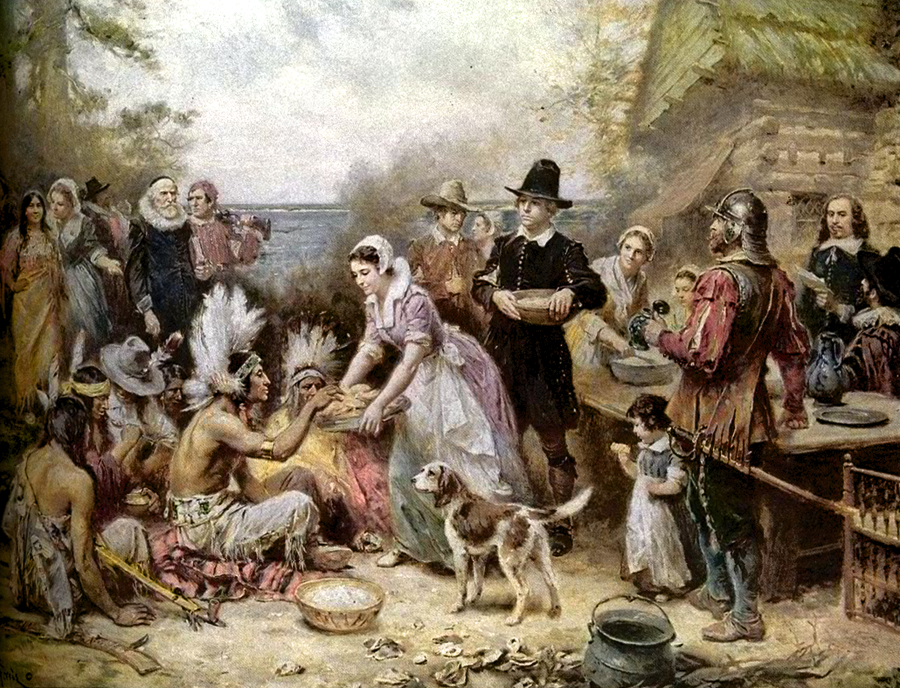

Everyone thinks Thanksgiving began with Pilgrims and Indians sitting down for a friendly meal in 1621, but the harvest celebration of 1621 was not called Thanksgiving and was not repeated every year. The event wasn’t even labeled as a “thanksgiving” by the people who participated in it. This story is a myth that was sparked in the mid-1800s when English accounts of the 1621 harvest event resurfaced and fueled the American imagination. The myth is that friendly Indians, unidentified by tribe, welcome the Pilgrims to America, teach them how to live in this new place, sit down to dinner with them and then disappear, handing off America to white people. This sanitized version of history leaves out the brutal reality that followed.

What actually happened was far different from the cozy dinner party most people imagine. The 1621 festival was not the reverential day some picture but was more like a harvest festival where about 50 Pilgrims and 90 Wampanoag people got together and partied, likely with games, races, and mark shooting.

The Real First Thanksgiving Wasn’t Even First

Even if it had been a thanksgiving, it wouldn’t have been the first one in North America, as many Native American tribes held ceremonies to give thanks, and many other European settlers did too. Spanish colonizers were celebrating thanksgiving ceremonies decades before the Pilgrims ever set foot in Massachusetts. In 1565, nearly 60 years before Plymouth, a Spanish fleet came ashore and planted a cross in the sandy beach to christen the new settlement of St. Augustine, where 800 Spanish settlers shared a festive meal with the native Timucuan people.

Historian Michael Gannon claimed St. Augustine, Florida, was founded with a shared thanksgiving meal on September 8, 1565, celebrated 56 years before the Puritan Pilgrim thanksgiving at Plymouth Colony. But Florida wasn’t the only place with earlier thanksgiving celebrations. There were also documented thanksgiving events in Virginia and along the Rio Grande that preceded the famous Plymouth gathering.

Native Americans Never Needed Pilgrims to Teach Them Gratitude

One of the most insulting myths is that the Pilgrims taught Native Americans about thanksgiving, but this stems from ideas of Manifest Destiny and white savior sentiment since Native Americans already had rich cultures, extremely complex societies, and established traditions of celebrating harvests and giving gratitude. Native Americans had large and complex societies long before settlers arrived, already had established harvest celebrations, feast traditions and holidays of their own, and were well aware of the virtue of gratitude.

The idea that Indigenous peoples were uncivilized before Europeans arrived is completely backwards. These societies had sophisticated agricultural systems, trade networks, and spiritual practices that had existed for thousands of years before any European ship appeared on the horizon.

The Horrific Truth About Early “Thanksgiving” Celebrations

Here’s what they don’t teach you in elementary school: the next official “day of thanksgiving” after 1621 was after settlers massacred more than 400 Pequot men, women and children, with Governor Bradford’s journal decreeing that for the next 100 years, every Thanksgiving Day ordained by a governor would honor this bloody victory. These weren’t celebrations of gratitude and harmony – they were victory parties after genocide.

In 1637, settlers retaliated for a purportedly murdered Pilgrim by burning a Wampanoag village, killing 500 men, women and children, with animosities culminating in King Philip’s War. The pattern was clear: thanksgiving celebrations often followed violent confrontations where Native Americans were slaughtered.

Squanto’s Devastating Story Gets Whitewashed

The famous story of Tisquantum, called “Squanto,” is another example of how history gets sanitized. Although Squanto did help the Pilgrims after the Mayflower landed, he was actually kidnapped by Englishmen in 1614 and sold into slavery in Spain, then sold again and moved to England where he learned English, and when he returned to his tribal land in 1619, he found that everyone in his tribe had died from smallpox.

Think about that for a moment – Squanto wasn’t some friendly guide who happened to speak English. He was a kidnapping and slavery survivor who came home to find his entire community wiped out by disease. His travels acquainted him with more of the world than any Pilgrim encountered, having crossed the Atlantic perhaps six times and lived in Maine, Newfoundland, Spain, and England.

The Political Reality Behind the 1621 Feast

Wampanoag leader Ousamequin reached out to the English at Plymouth not because he was innately friendly, but because his people had been decimated by epidemic disease, and he saw the English as an opportunity to fend off his tribal rivals. This wasn’t about friendship – it was about survival and strategic alliances.

Whatever the plague was, it decimated Indigenous groups in the region where Plymouth Colony would be founded, with the Wampanoag nation losing an estimated two-thirds of its population, and by 1620, this weakness provided an opportunity for the rival Narragansett group to subjugate the remaining Wampanoags. The alliance with the English was a desperate political move, not a heartwarming cultural exchange.

How the Myth Got Created in the 1800s

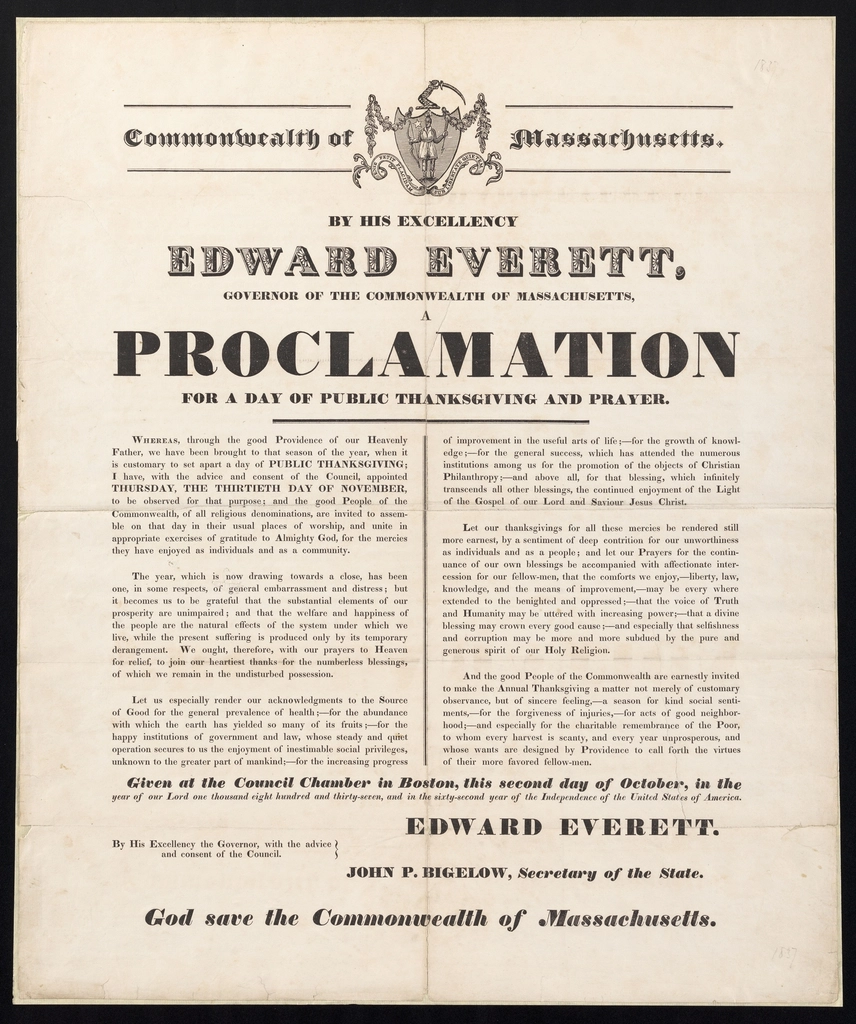

Romanticized paintings and stereotypical images of “Pilgrims” and “Indians” celebrating the “First Thanksgiving” became part of national nostalgia and Manifest Destiny sentiment as the United States pushed west, with Sarah Josepha Hale leading a campaign for a national Thanksgiving holiday. The white Protestant stock was unhappy about European Catholics and Jews, wanting to assert cultural authority through this national founding myth, and this mythmaking was impacted by racial politics when Indian Wars were ending.

The timing wasn’t coincidental. Creating a sanitized origin story about peaceful colonization helped justify westward expansion and ongoing displacement of Native peoples. It was propaganda disguised as history.

Abraham Lincoln Made It Official During War

Thanksgiving didn’t become an annual tradition until the 1800s when magazine editor Sara Josepha Hale lobbied five US Presidents to make it an annual holiday, with President Abraham Lincoln finally making Thanksgiving a federal holiday in 1863. The formation of Thanksgiving as an official United States holiday began in November 1863 during the Civil War, when President Lincoln established it as a way to improve relations between northern and southern states as well as the U.S. and tribal nations.

But there’s a dark context to Lincoln’s timing. Just a year prior, a mass execution took place of Dakota tribal members after corrupt federal agents kept them from receiving food and provisions, leading to the Dakota War of 1862, with Lincoln ordering 38 Dakota men to die from hanging. Lincoln felt Thanksgiving offered an opportunity to bridge hard feelings among Natives and the federal government.

King Philip’s War Shattered the Peace

The alliance between Wampanoags and colonists didn’t last long. Massasoit had maintained a long-standing agreement with the colonists, but Metacom, his younger son who became tribal chief in 1662, forsook his father’s alliance after repeated violations by the colonists. King Philip’s War is considered the bloodiest war per capita in U.S. history, leaving several hundred colonists dead and dozens of English settlements destroyed, with thousands of Indians killed, wounded or captured and sold into slavery.

After 14 months of horrific fighting, Metacom fled to his secret headquarters at Mount Hope in Rhode Island, where he was killed in August 1676, then hanged, beheaded, drawn and quartered, with his head placed on a spike and displayed at Plymouth Colony for two decades. This brutal display happened just 55 years after that supposedly harmonious first feast.

The Menu Wasn’t What You Think

The first Thanksgiving meal in Plymouth probably had little in common with today’s traditional holiday spread, with no record of a big roasted bird at the feast, though the Wampanoag brought deer and there would have been lots of local seafood plus pumpkin. The sweet cranberry sauce that many look forward to would have required sugar, which wasn’t generally available until 50 years later, and while pies weren’t unknown, early European settlers had no access to butter or wheat flour.

Sobaheg, a Wampanoag dish consisting of stewed corn, roots, beans, squash and meat, may have been served, along with locally available foods such as clams, lobsters, cod, eel, onions, carrots, turnips and various greens. The feast was probably more like a Native American harvest celebration than the turkey dinner we know today.

Native Americans Observe a Day of Mourning Instead

Since 1970, Indigenous people and their allies have gathered at noon on Cole’s Hill in Plymouth to commemorate a National Day of Mourning on the US Thanksgiving holiday, as many Native people do not celebrate the arrival of the Pilgrims since Thanksgiving Day is a reminder of the genocide of millions of Native people. The first National Day of Mourning demonstration was held in 1970 after Frank “Wamsutta” James’s speaking invitation was rescinded from a Massachusetts Thanksgiving Day celebration, so he delivered his speech on Cole’s Hill next to a statue of Ousamequin.

Hundreds of people descended onto Cole’s Hill in Plymouth to honor Indigenous ancestors and Native resilience, with speakers saying “what did we, the Indigenous people of this continent, get in return for this kindness? Genocide, the theft of our lands, the destruction of our traditional ways of life, slavery, starvation and never-ending oppression”. This gathering happens every year while most Americans are eating turkey.

Modern Thanksgiving Marketing Continues the Lie

It’s a misconception that the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade was always a celebration in honor of Thanksgiving, as originally it was the Macy’s Christmas Parade. Even our modern Thanksgiving traditions have been shaped by commercial interests rather than historical accuracy.

Sarah Josepha Hale, editor of a popular early-19th century women’s magazine, printed Thanksgiving menus and recipes that we now consider traditional Thanksgiving fare, like roast turkey and mashed potatoes. Much of what we think of as “traditional” Thanksgiving food was actually created by magazine editors trying to sell a specific vision of American domesticity.

The Ongoing Impact of These Myths

The Thanksgiving myth brings native people into the story of national origins, but then they disappear, with Pilgrims and their descendants carrying on while native people are just gone, though native people never went anywhere. Origin stories like the Thanksgiving one are particularly sticky as they underpin a group’s raison d’être, and fixing or changing the story risks muddying the plot and tearing apart the group.

This isn’t just about correcting historical facts – it’s about understanding how these myths continue to harm Native communities today. When we teach children that Indigenous peoples willingly handed over their land and then disappeared, we’re perpetuating the idea that their current struggles don’t matter. For the last 50 years, the Wampanoag Indians have marked Thanksgiving as a National Day of Mourning, spending the holiday reflecting on a history of genocide, land theft and cultural assault.

Conclusion

The real origins of Thanksgiving reveal a story far more complex and darker than the elementary school version most Americans grew up with. What began as strategic political alliances and harvest celebrations became weaponized into justification for genocide and land theft. The sanitized myth created in the 1800s served specific political purposes – uniting a fractured nation around a false origin story while erasing the voices and experiences of Indigenous peoples.

Understanding these true origins doesn’t mean we can’t gather with family or express gratitude. But it does mean we should acknowledge the full history and listen to Native voices who have been trying to tell their side of the story for decades. Maybe it’s time we started learning from that truth instead of hiding behind comfortable lies. What would Thanksgiving look like if we actually honored the people who were here first?