The Man Behind the Legend

Paul Revere was born in Boston’s North End on December 21, 1734, the third of nine children and oldest surviving son to Apollos Rivoire, a French Huguenot who emigrated to Boston at thirteen. His father anglicized the family name to Paul Revere, passing his goldsmith trade to his son. At the age of thirteen, Paul Revere left school and became an apprentice to his father, with silversmithing affording young Paul connections with a cross-section of Boston society that would serve him well during the American Revolution. When tragedy struck and his father died when Paul was just nineteen, he suddenly became responsible for supporting his mother and siblings while taking over the family business.

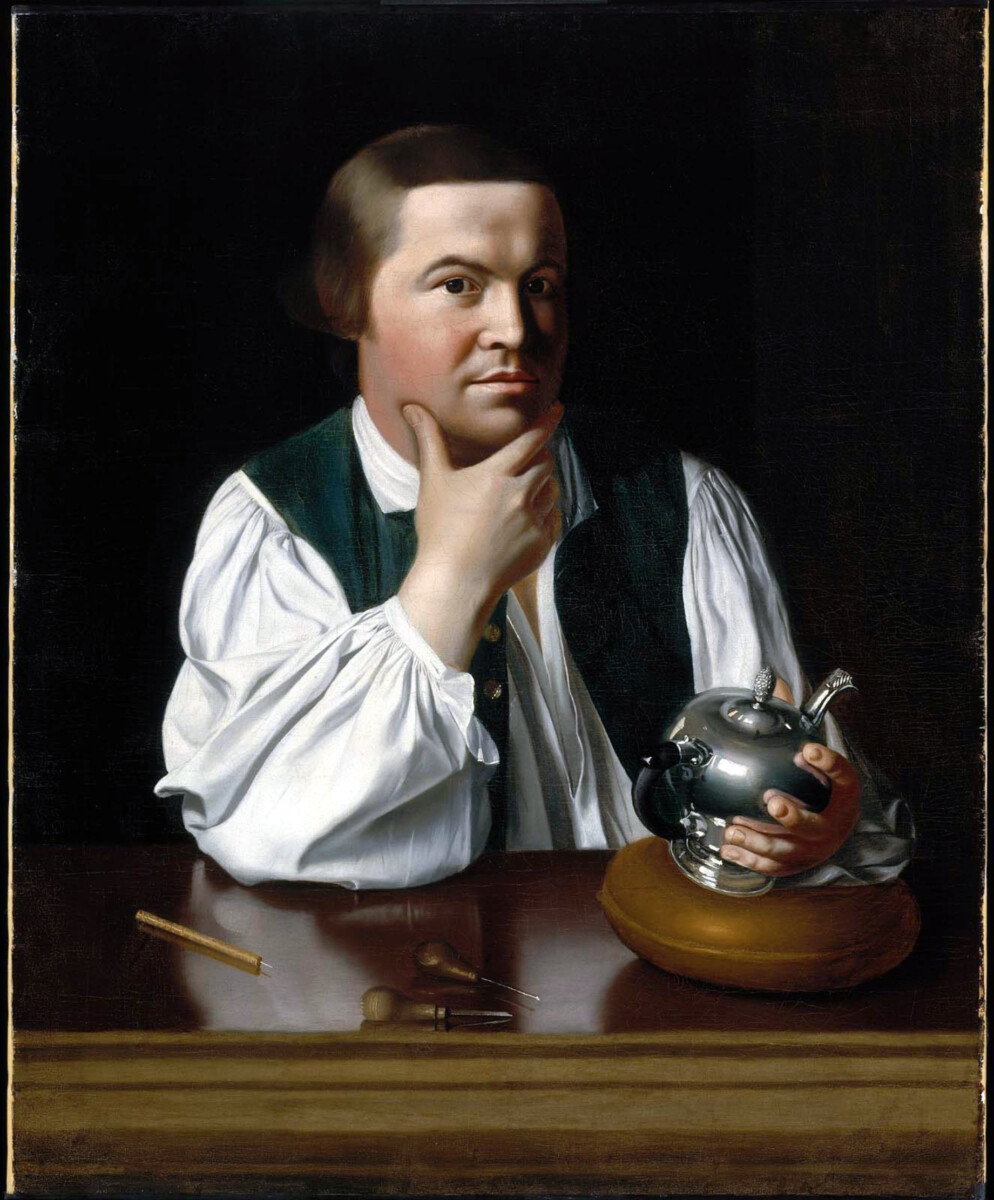

A Silversmith’s Life in Colonial Boston

Revere’s primary vocation was that of a goldsmith, a trade he learned from his father, and although goldsmiths worked in both gold and silver, they are generally referred to today as silversmiths. His silver shop was the cornerstone of his professional life for more than 40 years, and as the master craftsman, Revere was responsible for both the workmanship and the quality of the metal alloy used, employing numerous apprentices and journeymen to produce pieces ranging from simple spoons to magnificent tea sets.

Revere turned to various business ventures to augment his income when the colonial economy faltered during a recession, and during the economic depression that followed the French and Indian War, he began working as a copperplate engraver. He produced illustrations for books and magazines, business cards, political cartoons, bookplates, a song book, and bills of fare for taverns.

Revolutionary Connections and the Boston Tea Party

In the mid-1760s, as tensions were rising between the colonists and the British, Revere joined the rebellious Sons of Liberty in 1765. Revere took part in the Stamp Act protests in 1765, which eventually led the Crown to repeal a tax that ignited the colonists’ hatred of taxation without representation. In 1773 he donned Indian garb and joined 50 other patriots in the Boston Tea Party protest against parliamentary taxation without representation. Revere was one of the ringleaders in the Boston Tea Party of December 16, when colonists dumped tea from the Dartmouth and two other ships into the harbor.

The Professional Courier Before the Famous Ride

In 1774 and 1775, the Boston Committee of Correspondence and the Massachusetts Committee of Safety employed Paul Revere as an express rider to carry news, messages, and copies of important documents as far away as New York and Philadelphia. From December 1773 to November 1775, Revere served as a courier for the Boston Committee of Public Safety, traveling to New York and Philadelphia to report on the political unrest in Boston, with research documenting 18 such rides. Paul Revere had made the same ride a week and a half earlier, making lots of rides, in fact, including one on Dec. 13, 1774, when he rode all the way to Portsmouth, N.H., to warn the patriots that the King’s troops were on their way to seize gunpowder from Fort William and Mary in New Castle.

The Signal System: Truth Behind the Lanterns

At the same time as Revere and Dawes departed Boston around 10pm, two signal lanterns briefly showed from the Old North Church steeple, a prearranged signal designed by Revere to alert the alarm network across the Harbor, with the famous “one if by land, two if by sea” signaling that the British would row across Boston harbor instead of marching out over the neck. Robert Newman, the sexton of Boston’s Old North Church, used a lantern signal to warn colonists in Charlestown of the British Army’s advance by way of the Charles River. This system wasn’t improvised on the spot but was part of a carefully planned warning network that Revere had helped establish.

Multiple Riders, Not a Solo Mission

Accompanied by William Dawes, a tanner by trade, Revere and his fellow militiaman, under direction of General Joseph Warren, set out late at night on slightly different routes to Lexington to meet up with Samuel Adams and John Hancock. The essential myth is that Revere rode on his own, when in reality, Dawes was also a leading rider, and most scholars agree that there were as many as 40 riders assigned to carry the warning through northern and eastern Massachusetts. Revere and Dawes were not the only riders – they were the only two to be noted in poetry, as Samuel Prescott and Israel Bissell were also tasked to undertake the mission, with Bissell being the person to ride the farthest distance of all.

What Paul Revere Actually Shouted

Paul Revere never shouted the legendary phrase later attributed to him (“The British are coming!”) as he passed from town to town, since the operation was meant to be conducted as discreetly as possible with scores of British troops hiding out in the Massachusetts countryside. Furthermore, colonial Americans at that time still considered themselves British; if anything, Revere may have told other rebels that the “Regulars” – a term used to designate British soldiers – were on the move. Revere’s warning, according to eyewitness accounts of the ride and Revere’s own descriptions, was “The Regulars are coming out.” When Paul Revere and others rode to warn rebel leaders that soldiers were heading their way, they would never have shouted “The British are coming!” because, simply put, they were all still British – imagine someone running down a road in Concord, MA today shouting “The Americans are coming!” and you’ve got the idea.

The Capture and End of Revere’s Ride

A short distance outside of Lexington, Revere, Dawes, and Dr. Samuel Prescott were overtaken by a British patrol, and while Prescott and Dawes escaped, Revere was held for some time, questioned, and let go. Before he was released, however, his horse was confiscated to replace the tired mount of a British sergeant, leaving Revere alone on the road to return to Lexington on foot in time to witness the latter part of the battle on Lexington Green. Revere never reached Concord, as the poem inaccurately recounts – overtaken by the British, the three riders split up and headed in different directions, with Revere temporarily detained by the British at Lexington and Dawes losing his way after falling off his horse, leaving Prescott the task of alerting Concord’s residents.

Samuel Prescott: The Forgotten Hero of Concord

Joining the horseback mission on a third route was Samuel Prescott, American physician, who was heading home to Concord from Lexington; Dr. Prescott was the only one to actually reach Concord where he gave word to the town sentry to ring the First Parish Church bell. Samuel Prescott was the person who actually made it to Concord. While Paul Revere gets all the fame, it was actually this young doctor who completed the most crucial part of the mission – alerting the people of Concord where the largest cache of military supplies was stored.

Longfellow’s Poem: Creating the Myth

Revere saddled up April 18, 1775, but it wasn’t until 86 years later that Longfellow composed his well-known poem, pulling the Boston silversmith from the lesser-read pages of America’s nascent historical record into the realm of folk hero. The fabrication of the Revere story can be traced to 1860, when on the eve of the American Civil War, New England poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow penned a poem entitled “Paul Revere’s Ride” with his purpose being to stir patriotic sentiment in New England by reminding his countrymen of their past. Longfellow published Paul Revere’s Ride in The Atlantic Monthly magazine, which appeared on newsstands the day South Carolina seceded, and at the time, people viewed it as a call to arms for the North.

Historical Impact Beyond the Famous Night

Revere, a silversmith by trade, also produced copperplate engravings for book and magazine illustrations, portraits and political drawings that supported the nascent Patriot movement, with his most effective piece of anti-British propaganda being “The Bloody Massacre,” a full-color rendering of the 1770 melee that came to be known as the Boston Massacre, printed just weeks after British troops opened fire on an unarmed crowd of rabble-rousing Bostonians. During the war, Revere broke new ground in battlefield medicine, and in March 1776, he was able to identify a fallen soldier on the Bunker Hill battlefield as Dr. Joseph Warren by recognizing the dentures he had made for Warren from walrus teeth and iron.

The Post-War Industrial Pioneer

Following the war, Revere returned to his silversmith trade, using the profits from his expanding business to finance his work in iron casting, bronze bell and cannon casting, and the forging of copper bolts and spikes, becoming in 1800 the first American to successfully roll copper into sheets for use as sheathing on naval vessels. He set up a rolling mill for the manufacture of sheet copper at Canton, Massachusetts, and from this factory came sheathing for many U.S. ships, including the Constitution, and for the dome of the Massachusetts State House. The post-Revolutionary Revere became a prosperous entrepreneur and respected citizen, owning a silver shop, hardware shop, foundry, and copper mill.

The Real Legacy vs. The Legend

No one outside of the Boston area knew who Paul Revere was until Longfellow wrote Paul Revere’s Ride, and even during his lifetime, Bostonians knew Revere as a successful businessman who had lots of friends – that’s how his obituary read after he died on May 10, 1818, and it didn’t even mention the ride. Before Longfellow’s poem, his midnight ride was a mere footnote in history and was deemed so unimportant that it wasn’t even mentioned in Revere’s obituaries when he died. The truth is that Paul Revere’s real contributions to American independence were far more substantial and varied than one dramatic night would suggest – he was a master craftsman, political organizer, intelligence courier, and industrial pioneer who helped build the economic foundation of the new nation.