Mona Lisa by Leonardo da Vinci

It’s hard to imagine that the Mona Lisa, the world’s most famous painting, was ever anything but beloved. Yet, when Leonardo da Vinci finished it around 1506, it was just another portrait among many, and it didn’t captivate audiences. In fact, for centuries, critics brushed it off as a simple, unremarkable depiction. Some even complained about the sitter’s mysterious smile, calling it unsettling. It wasn’t until the 20th century—after its 1911 theft from the Louvre—that public fascination exploded. Today, millions visit Paris each year to see it, and the painting is insured for nearly $900 million.

Impression, Sunrise by Claude Monet

Monet’s Impression, Sunrise, painted in 1872, gave Impressionism its name, but it was initially ridiculed. Critics in Paris sneered at its loose brushwork, calling the painting unfinished and childish. They saw Monet’s depiction of a hazy Le Havre harbor as a far cry from realism, which dominated the art world at the time. Louis Leroy, a critic, even coined the term “Impressionist” as an insult. Today, this painting is a national treasure in France and considered the spark that ignited modern art.

Starry Night by Vincent van Gogh

When Vincent van Gogh painted Starry Night in 1889, hardly anyone cared—or even liked it. Van Gogh himself thought it was a failure, and the art establishment dismissed it as wild and clumsy. His swirling skies and bold color choices were simply too strange for the late 19th century. Van Gogh sold only one painting in his lifetime. Now, Starry Night is celebrated as one of the most recognized and beloved masterpieces in the world, housed at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

The Persistence of Memory by Salvador Dalí

Dalí’s surreal The Persistence of Memory, painted in 1931, was met with confusion and some mockery. Audiences and critics alike balked at the melting clocks and dreamlike landscape. Many saw Dalí’s work as too bizarre, even questioning his sanity. But as surrealism gained momentum, so did the painting’s reputation. Today, it’s considered a masterpiece of 20th-century art, and Dalí is hailed for his imaginative genius.

Les Demoiselles d’Avignon by Pablo Picasso

When Picasso first revealed Les Demoiselles d’Avignon in 1907, friends and critics were stunned—in a bad way. Fellow artists called it monstrous, and the public was disturbed by the angular, abstract figures. Even Picasso’s close friend Henri Matisse reportedly loathed it. But this painting is now seen as a revolutionary work, marking the birth of Cubism. It’s one of the Museum of Modern Art’s greatest treasures.

No. 5, 1948 by Jackson Pollock

Pollock’s No. 5, 1948 didn’t just puzzle the public—it angered them. His chaotic “drip” technique looked like a mess to many, and critics scoffed at the idea that this could be high art. Some even called it a joke. But as attitudes toward abstract expressionism changed, Pollock’s work was reevaluated. In 2006, No. 5 sold for $140 million in a private sale, making it one of the world’s most expensive paintings.

The Scream by Edvard Munch

When Munch’s The Scream debuted in 1893, newspapers called it ugly and disturbing. Its raw emotion and distorted form were too much for many viewers, who were used to more serene and idealized images. Some critics dismissed it as the product of a troubled mind. Yet, over time, The Scream came to be seen as the ultimate expression of modern anxiety. Today, it’s an instantly recognizable symbol, and versions have sold for over $120 million at auction.

Water Lilies Series by Claude Monet

Monet’s Water Lilies, painted over three decades, were initially met with polite indifference. Critics in early 20th-century France thought they were self-indulgent and repetitive. Some even called them “decorative panels” rather than serious art. Monet struggled with failing eyesight, and his blurry technique was misunderstood. Now, these paintings are celebrated for their beauty and have drawn record crowds to the Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris.

Whistler’s Mother by James McNeill Whistler

Whistler’s Mother, formally titled Arrangement in Grey and Black No.1, shocked audiences in 1871. Critics thought it was dull and unflattering, and the Royal Academy almost refused to hang it. The painting’s stark simplicity felt cold to Victorian viewers, who preferred more sentimental portraits. Over time, the composition’s boldness and restraint won admiration, and the painting is now an American cultural icon.

Olympia by Édouard Manet

Manet’s Olympia, painted in 1863, scandalized Paris when first shown. The nude subject’s direct gaze was seen as brazen and vulgar, and critics condemned the painting as immoral. Even the French government was embarrassed by the uproar. As society’s views on art and sexuality shifted, Olympia became a symbol of modernity and artistic freedom. Today, it hangs in the Musée d’Orsay as a highlight of 19th-century art.

Composition VII by Wassily Kandinsky

When Kandinsky showed Composition VII in 1913, it left viewers baffled. With no recognizable subject and a riot of color and form, many wondered if he was just playing a joke. Critics accused Kandinsky of abandoning tradition and even called his work “madness on canvas.” But this painting is now considered a pivotal moment in abstract art. It’s studied in classrooms and museums worldwide and valued as a turning point for modern painting.

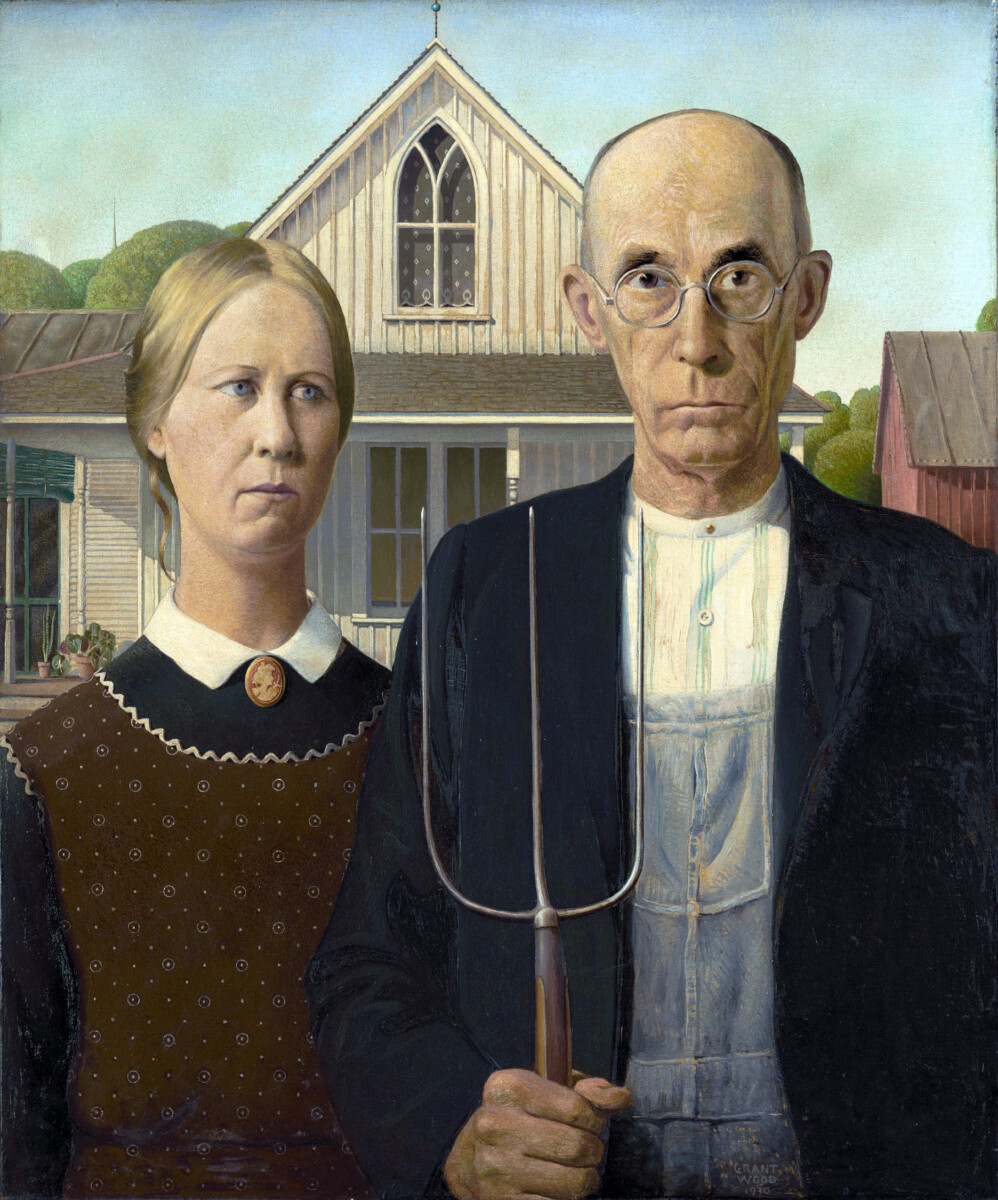

American Gothic by Grant Wood

American Gothic, painted in 1930, was met with both ridicule and confusion. Critics argued that it mocked rural Americans, while others thought it was just plain odd. Wood’s stern farmer and his daughter became the subject of jokes and satire. Over the decades, the painting took on new meaning, reflecting the resilience and dignity of everyday people. Today, it’s one of the most parodied and respected works in American art.

The Birth of Venus by Sandro Botticelli

When Botticelli completed The Birth of Venus in the late 1400s, the Catholic Church frowned on its pagan subject matter and open nudity. For centuries, the painting was tucked away in private collections, rarely seen by the public. Art critics snubbed it as out of step with Renaissance ideals. Now, The Birth of Venus is a quintessential symbol of beauty and Italian art, drawing millions to Florence’s Uffizi Gallery each year.

The Night Watch by Rembrandt van Rijn

Rembrandt’s The Night Watch, painted in 1642, was not warmly received. Some members of the Amsterdam militia, who commissioned the work, disliked its dramatic lighting and movement. They expected a formal group portrait, not Rembrandt’s bold, action-filled scene. Critics accused Rembrandt of poor composition, and the painting was cut down in size to fit a wall. Today, it’s celebrated for its innovation and is the pride of Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum.

Guernica by Pablo Picasso

Guernica, painted by Picasso in 1937, was met with mixed reviews and political controversy. Some critics called it confusing and ugly, while others felt it was too radical as a protest against war. The painting’s stark, black-and-white imagery shocked viewers at the Paris International Exposition. Over time, Guernica became a powerful anti-war symbol and is now one of the most influential political paintings ever created.

End