The Moral Crusade Behind the Temperance Movement

The temperance movement, discouraging the use of alcoholic beverages, had been active and influential in the United States since at least the 1830s. The country’s first serious anti-alcohol movement grew out of a fervor for reform that swept the nation in the 1830s and 1840s. Many abolitionists fighting to rid the country of slavery came to see drink as an equally great evil to be eradicated – if America were ever to be fully cleansed of sin. By 1830, the average American over 15 years old consumed nearly seven gallons of pure alcohol a year – three times as much as we drink today.

The temperance movement, rooted in America’s Protestant churches, first urged moderation, then encouraged drinkers to help each other to resist temptation, and ultimately demanded that local, state, and national governments prohibit alcohol outright. The temperance movement began amassing a following in the 1820s and ’30s, bolstered by the religious revivalism that was sweeping the nation at that time. Picture the scene: traveling preachers wandering through dusty towns, convincing folks that demon rum was Satan’s personal calling card.

Women Warriors Leading the Charge

The roots of what became Prohibition in 1920 started in the 19th century with the Temperance Movement, principally among women who protested against the abuse of alcohol and how it caused men to commit domestic violence against women. By 1831, there were 24 women’s organizations dedicated to temperance. It was an appealing cause because it sought to end a phenomenon that directly affected many women’s quality of life. Temperance was painted as a religious and moral duty that paired well with other feminine responsibilities.

Their organization, the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), became a force to be reckoned with, their cause enhanced by alliance with Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and other women battling for the vote. By the late 19th century the WCTU, led by the indomitable Frances Willard, could claim some significant successes – it had lobbied for local laws restricting alcohol and created an anti-alcohol educational campaign that reached into nearly every schoolroom in the nation. In 1881, the WCTU began to lobby for legally mandated temperance instruction in schools. By 1901, federal law required “scientific temperance” instruction in all public schools, federal territories’ and military schools.

The Anti-Saloon League’s Political Machine

Rev. Howard Hyde Russell founded the Anti-Saloon League (ASL) in 1893. Under the leadership of Wayne Wheeler the ASL stressed political results and perfected the art of pressure politics. It did not demand that politicians change their drinking habits, only their votes in the legislature. Other organizations like the Prohibition Party and the WCTU soon lost influence to the better-organized and more focused ASL. Unlike the WCTU, which was guided by Francis Willard’s “do everything” philosophy, the ASL under Wheeler focused entirely on the goal of passing Prohibition–using whatever tactics were necessary. To carry out this agenda, the Anti-Saloon League developed its own publishing house, the American Issue Publishing Company.

During the League’s heyday, it issued more than forty tons of anti-liquor publications every month. The last wave of temperance in the United States saw the rise of the Anti-Saloon League (ASL), which successfully pushed for National Prohibition from its enactment in 1920 to its repeal in 1933. This heavily prohibitionist wave attracted a diverse coalition: doctors, pastors, and eugenicists; Klansmen and liberal internationalists; business leaders and labor radicals; conservative evangelicals and liberal theologians.

World War I: The Perfect Storm

World War I provided the final solid push toward a constitutional amendment by making temperance synonymous with patriotism, thrift and prudence. The league used the after effects of World War I to push for national prohibition because there was a lot of prejudice and suspicion of foreigners following the war. Many reformers used the war to get measures passed and a major example of this was national prohibition. The league was successful in getting many states to ban alcohol prior to 1917 by claiming that to drink was to be pro-German and this had the intended results.

Additionally, many saloons were immigrant-dominated which further supported the narrative that the Anti-Saloon League was pushing for. Another factor that led to the passage of the Volstead Act was the idea that in order to feed the allied nations there was a greater need for the grain that was being used to make whiskey. The United States’ entry into World War I provided an additional push, as conserving grain for the war effort made alcohol seem like an unnecessary luxury. By the end of the war, support for Prohibition had grown strong enough to pass the 18th Amendment through Congress and secure ratification by the required three-fourths of the states.

The 18th Amendment: Victory at Last

The amendment was proposed by Congress on December 18, 1917, and ratified by the requisite number of states on January 16, 1919. The Eighteenth Amendment was repealed by the Twenty-first Amendment on December 5, 1933, making it the only constitutional amendment in American history to be repealed. After a temporary wartime prohibition to save grain during World War I, the Eighteenth Amendment was submitted by Congress for state ratification. It was quickly ratified within a year and would stand as law for the next 13 years.

In just 13 months enough states said yes to the amendment that would prohibit the manufacture, sale, and transportation of alcoholic liquors. The amendment worked at first: liquor consumption dropped, arrests for drunkenness fell, and the price for illegal alcohol rose higher than the average worker could afford. Alcohol consumption dropped by 30 percent and the United States Brewers’ Association admitted that the consumption of hard liquor was off 50 percent during Prohibition. One year and a day after its ratification, prohibition went into effect—on January 17, 1920—and the nation became officially dry.

The Volstead Act: Putting Teeth in the Law

The National Prohibition Act, known informally as the Volstead Act, was an act of the 66th United States Congress designed to execute the 18th Amendment (ratified January 1919) which established the prohibition of alcoholic drinks. The Anti-Saloon League’s Wayne Wheeler conceived and drafted the bill, which was named after Andrew Volstead, chairman of the House Judiciary Committee, who managed the legislation. President Woodrow Wilson vetoed the bill, Congress overrode his veto, and the bill went through on October 28, 1919. The Volstead Act went into play on January 16, 1920, where it became a challenge for the United States Supreme Court to navigate through.

Title II of the Volstead Act, “Permanent National Prohibition,” which was defined as “intoxicating beverages” containing greater than 0.5 percent alcohol. This section also set forth the fines and jail sentences for the manufacture, sale and movement of alcoholic beverages, as well as set forth regulations that described those who would enforce the laws, what search and seizure powers law enforcement had or did not have, as well as how adjunction of violations would be in place, among many others.

The Great Enforcement Failure

Enforcing Prohibition proved to be extremely difficult. The illegal production and distribution of liquor, or bootlegging, became rampant, and the national government did not have the means or desire to try to enforce every border, lake, river, and speakeasy in America. In fact, by 1925 in New York City alone there were anywhere from 30,000 to 100,000 speakeasy clubs. The demand for alcohol was outweighing (and out-winning) the demand for sobriety. Prohibition officially became law in January 1920: 1,520 Federal Prohibition agents were tasked with the job of enforcing prohibition across America. It quickly became clear that this would not be a simple task.

The sums of money being exchanged during the dry era proved a corrupting influence in both the federal Bureau of Prohibition and at the state and local level. Police officers and Prohibition agents alike were frequently tempted by bribes or the lucrative opportunity to go into bootlegging themselves. The growth of the illegal liquor trade under Prohibition made criminals of millions of Americans. As the decade progressed, court rooms and jails overflowed, and the legal system failed to keep up.

The Rise of Organized Crime

Prohibition practically created organized crime in America. It provided members of small-time street gangs with the greatest opportunity ever — feeding the need of Americans coast to coast to drink beer, wine and hard liquor on the sly. The term “organized crime” didn’t really exist in the United States before Prohibition. Criminal gangs had run amok in American cities since the late 19th-century, but they were mostly bands of street thugs running small-time extortion and loansharking rackets in predominantly ethnic Italian, Jewish, Irish and Polish neighborhoods.

By the early 1920s, profits from the illegal production and trafficking of liquor were so enormous that gangsters learned to be more “organized” than ever, employing lawyers, accountants, brew masters, boat captains, truckers and warehousemen, plus armed thugs known as “torpedoes” to intimidate, injure, bomb or kill competitors. The new alcohol trafficking gangs during Prohibition also crossed ethnic lines, with Italians, Irish, Jews and Poles working with each other, although inter-gang rivalries, shootings, bombings and killings would shape the 1920s and early ’30s. The demand for illegal beer, wine and liquor was so great during the Prohibition that mob kingpins like Capone were pulling in as much as $100 million a year in the mid-1920s ($1.4 billion in 2018) and spending a half million dollars a month in bribes to police, politicians and federal investigators.

The Crime Wave and Violence

In one study of more than 30 major U.S. cities during the Prohibition years of 1920 and 1921, the number of crimes increased by 24%. Additionally, theft and burglaries increased by 9%, homicides by 13%, assaults and battery rose by 13%, drug addiction by 45%, and police department costs rose by 11.4%. More than 1,000 people were killed in New York alone in Mob clashes during Prohibition. The period sparked a revolution in organized crime, generating frameworks and stacks of cash for major crime families that, though far less powerful, still exist to this day.

For example, one study found that organized crime in Chicago tripled during Prohibition. Mafia groups and other criminal organizations and gangs had mostly limited their activities to prostitution, gambling, and theft until 1920, when organized “rum-running” or bootlegging emerged in response to Prohibition. Homicides, burglaries, and assaults consequently increased significantly between 1920 and 1933. In the face of this crime wave, law enforcement struggled to keep up.

The Unintended Consequences

One of the most profound effects of Prohibition was on government tax revenues. Before Prohibition, many states relied heavily on excise taxes in liquor sales to fund their budgets. In New York, almost 75% of the state’s revenue was derived from liquor taxes. With Prohibition in effect, that revenue was immediately lost. At the national level, Prohibition cost the federal government a total of $11 billion in lost tax revenue, while costing over $300 million to enforce. The most lasting consequence was that many states and the federal government would come to rely on income tax revenue to fund their budgets going forward.

One of the legal exceptions to the Prohibition law was that pharmacists were allowed to dispense whiskey by prescription for any number of ailments, ranging from anxiety to influenza. Bootleggers quickly discovered that running a pharmacy was a perfect front for their trade. As a result, the number of registered pharmacists in New York State tripled during the Prohibition era.

The Great Depression Changes Everything

By that time, though, the Great Depression was in full swing, and the nation’s mood had changed. The 18th Amendment, which ushered in Prohibition, had forced an estimated 250,000 alcohol industry employees out of work. Now, with a quarter of the U.S. labor force jobless and people growing increasingly desperate, this seemed absurd. What’s more, income tax collections had dropped precipitously (along with personal incomes), and the federal government was desperate for revenue, having forfeited an estimated $11 billion in alcohol-related taxes over the course of Prohibition.

As the 1920s gave way to the 1930s and the Great Depression worsened, many Americans questioned the need to focus on Prohibition’s enforcement while millions lost jobs and stood in bread lines. Politically, the tide began to turn in 1930, when Democrats took back Congress in the midterm elections, arguing that repeal would create jobs and raise revenue for the federal government. When Franklin D. Roosevelt ran for president in 1932, the repeal of Prohibition was a key part of his platform. Roosevelt swept into the Presidency offering change and hope in a time of desperate economic need.

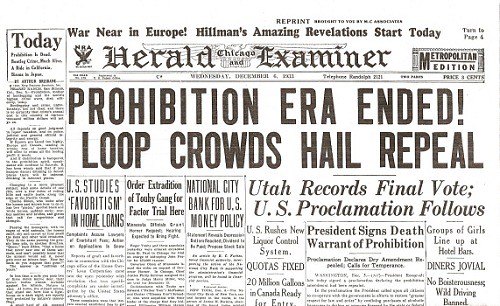

The End of the Noble Experiment

Roosevelt ended up trouncing the Republican Hoover with 57.4 percent of the popular vote. The Democrats likewise made enormous gains in both houses of Congress, which passed the 21st Amendment to repeal Prohibition even before FDR officially took office. The amendment then went to the states, which ratified it in a rapid-fire fashion. In December 1933, Utah supplied the 36th and final vote needed to end Prohibition once and for all. The country celebrated by drinking beer and wine that, while low in alcohol, was finally legal after 13 years. Full repeal of Prohibition, including higher-alcohol spirits, came several months later on December 5, 1933.

But it did fund much of the New Deal, with alcohol and other excise taxes bringing in $1.35 billion, nearly half the federal government’s total revenue, in 1934. Repeal likewise helped tame unemployment. “Before Prohibition, the distilling and brewing industries were the fifth or sixth largest employer in America,” Okrent says. “So bringing it back was an incredible, privately financed jobs program.” The decision to repeal a constitutional amendment was unprecedented and came as a response to the crime and general ineffectiveness associated with prohibition.

Conclusion: Lessons From America’s Noble Experiment

Prohibition, failing fully to enforce sobriety and costing billions, rapidly lost popular support in the early 1930s. In 1933, the 21st Amendment to the Constitution was passed and ratified, ending national Prohibition. For 13 years, the United States was officially “dry,” but from its very inception, the law was controversial and difficult to enforce, and its effect on the country’s problems with alcohol was debatable. In 1933, Prohibition came to end with the ratification of the 21st Amendment, the first and only time in American history where ratification of a constitutional amendment signaled the repeal of another.

The story of Prohibition’s rise and fall reads like a cautionary tale about the complexities of legislating morality in a diverse democracy. What began as a moral crusade to save American families from the scourge of alcohol ended up creating unprecedented levels of organized crime, corruption, and social chaos. The combination of wartime patriotism, women’s rights advocacy, and religious fervor proved powerful enough to amend the Constitution, but the harsh realities of enforcement, economic hardship, and unintended consequences ultimately brought the “noble experiment” to its knees.

Did you expect that one simple amendment could create such a transformation in American society?