The Speeding President Who Broke the Law in Broad Daylight

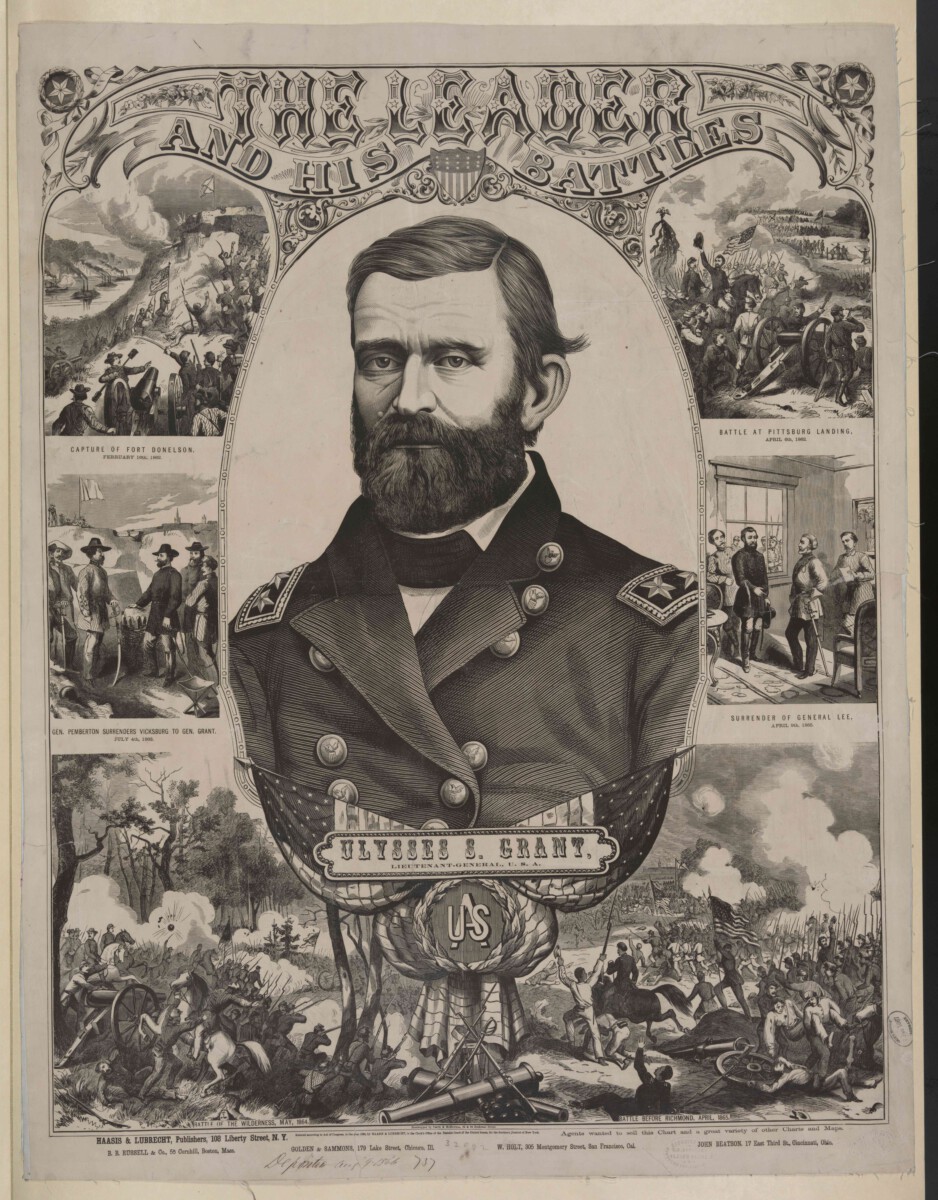

Picture this: the President of the United States being pulled over by a police officer for reckless driving through the streets of Washington D.C. Grant’s reckless “driving” is the only recorded instance of a sitting or former U.S. president being placed under arrest, making his 1872 brush with the law the first and so far only time a United States president has been arrested while in office. The year was 1872 and President Ulysses S. Grant found himself caught on the wrong side of the law by William H. West—a young former slave and Civil War veteran who joined the Washington, D.C., Metropolitan Police Department (MPD) only one year prior. This wasn’t some minor traffic infraction either. “Gen. Grant was an ardent admirer of a good horse and loved nothing better than to sit behind a pair of spirited animals,” the Star reported. “He was a good driver, and sometimes ‘let them out’ to try their mettle.”

When Speed Demons Ruled the White House

Two days prior to the president’s arrest, a buggy driver struck a woman and her 6-year-old son at the corner of 13th and M streets. The police dispatched Metro Police’s Officer West to investigate complaints of speeding carriages. Officer West was a former enslaved person who had served with distinction in a United States Colored Troops infantry regiment during the Civil War. A formerly enslaved man who had served in a United States Colored Troops infantry regiment during the Civil War, West joined the Washington, D.C. Metropolitan Police Force in 1871. What happened next reads like something out of a Hollywood script. According to the Evening Star article, West was speaking to witnesses the day after the incident when another group of carriages, including one piloted by Grant, sped toward the scene. West held up his hands for the group to stop and told the president he was going too fast. “Your fast driving, sir, has set the example for a lot of other gentlemen,” West said, according to the article.

The Presidential Promise That Lasted All of One Day

Grant’s first encounter with Officer West should have been a wake-up call. He stopped the president for speeding in his horse and buggy and gave him a warning for excessive speed before sending him on his way. The president apologized profusely and promised to be more careful. The president apologized, promised it wouldn’t happen again and galloped away. But Grant simply couldn’t resist the thrill of speed. But Grant could not curb his need for speed. The next evening, West was patrolling at the corner of 13th and M streets when the president came barreling through again, this time speeding so fast that it took him an entire block to stop. The next day, on a very similar patrol, West witnessed the president repeating his behavior and thus, arrested him.

The Historic Arrest That Made Headlines

While arresting the president, West said, “I am very sorry, Mr. President, to have to do it, for you are the chief of the nation and I am nothing but a policeman, but duty is duty, sir, and I will have to place you under arrest.” President Grant was taken to the police station and released on a $20 bond—the equivalent to $430 today—and he did not contest the fine or the arrest. Now Grant was cocky and had a “smile on his face,” the Star reported, that made him look like “a schoolboy who had been caught in a guilty act by a teacher.” The entire scene must have been surreal for both men. Anyway, Grant and several of his speeding buddies also arrested went with West to the police station. The president of the United States was ordered to put up 20 bucks as collateral.

The Court Case Where a President Was a No-Show

A trial was held the next day. “Thirty-two ladies of the most refined character and surroundings voluntarily came into the court and testified against the drivers,” the Star story said. “The cases were contested bitterly.” The judge imposed “heavy fines” and a “scathing rebuke” to the speeding drivers, who didn’t include the president. He didn’t show up for court. The following day, the six men were given heavy fines and “a scathing rebuke” by the judge, but President Grant did not show up to court. Because of this absence, President Grant forfeited his $20 collateral. It was an extraordinary display of presidential privilege in action. Even after being arrested, Grant felt he was above appearing in court like any ordinary citizen.

The Questionable Historical Record of Presidential Speed

While Grant’s 1872 arrest story has become legendary, historians have raised questions about its authenticity. Park staff conducted newspaper research and were unable to find any articles from 1872 announcing President Grant’s arrest. Given that Washington, D.C. had seven daily newspapers at the time and 1872 was a bitterly divisive election year, the arrest would have made national headlines had it been announced by police or legal authorities in the city. However, there’s solid evidence that Grant had previous run-ins with the law. Interestingly, evidence from the time suggests that Grant was pulled over for speeding in 1866, when he was still Lieutenant General of the U.S. Army. Several months later, the Fourth of July issue of the Richmond Daily Dispatch reprinted a National Intelligencer article announcing that Grant was arrested a second time for speeding. “The General took the arrest very good humoredly, said it was an oversight, and rode over to the second Precinct station house and paid his fine.” However, in 2012, the D.C. chief of police, Cathy Lanier, told WTOP that the police department arrested Grant for speeding three times in the 1800s.

Nixon’s Narrow Escape From Criminal Justice

Fast-forward exactly one hundred years later, and another president found himself on the wrong side of the law—but Richard Nixon’s story took a dramatically different path. On the verge of being impeached, Nixon resigned the presidency on August 9, 1974, becoming the only U.S. president to do so. In all, 48 people were found guilty of Watergate-related crimes, but Nixon was pardoned by his vice president and successor Gerald Ford on September 8. Unlike Grant’s speeding tickets, Nixon faced potential federal criminal charges for his role in the Watergate cover-up. Criminal prosecution was still a possibility at the federal level. Nixon was succeeded by Vice President Gerald Ford as president, who on September 8, 1974, issued a full and unconditional pardon of Nixon, immunizing him from prosecution for any crimes he had “committed or may have committed or taken part in” as president.

The Pardon That Saved Nixon From Prison

In a televised broadcast to the nation, Ford explained that he felt the pardon was in the best interest of the country. He said that the Nixon family’s situation “is an American tragedy in which we all have played a part. It could go on and on and on, or someone must write the end to it. I have concluded that only I can do that, and if I can, I must.” The Nixon pardon was deeply controversial with the American public. Only 26% of Americans supported the pardon in one poll, with 59% opposed. Reporters interviewed outraged citizens. Ford’s decision effectively prevented Nixon from ever facing a criminal trial. Ford eventually agreed, and on September 8, 1974, he granted Nixon a “full, free, and absolute pardon” that ended any possibility of an indictment.

The Modern Era of Presidential Indictments

The landscape of presidential accountability changed dramatically in 2023 when history was made once again. In 2023, four criminal indictments were filed against Donald Trump, then a former president of the United States. Two indictments are on state charges (one in New York and one in Georgia) and two indictments (as well as one superseding indictment) are on federal charges (one in Florida and one in the District of Columbia). Donald Trump is the first former president in U.S. history to be criminally indicted. This marked a seismic shift from the Nixon era, when presidential immunity was assumed but not legally established. Across Trump’s four indictments, he has been charged with a total of 88 criminal counts.

The New York Conviction That Made History

He faced 34 criminal charges of falsifying business records in the first degree related to payments made to Stormy Daniels before the 2016 presidential election. The trial began on April 15, 2024; Trump was found guilty on all 34 counts on May 30, 2024. On January 10, 2025, Trump received an unconditional discharge of his sentence. On Thursday, former president Donald Trump was convicted on 34 felony counts by a New York jury. This was the first time a former president was convicted of a crime. The conviction represented a historic first—no former president had ever been found guilty of criminal charges in a court of law. The Manhattan case centered on hush money payments made during the 2016 election campaign, a far cry from Grant’s horse-and-buggy speeding tickets.

The Federal Cases That Tested Presidential Power

Trump was indicted in June 2023 in the United States District Court for the Southern District of Florida in a federal indictment related to classified government documents. Trump faced 40 criminal charges alleging mishandling of sensitive documents and conspiracy to obstruct the government in retrieving these documents. The classified documents case presented unprecedented questions about presidential power and accountability. On July 15, 2024, Judge Aileen Cannon dismissed the case, ruling Jack Smith’s appointment as special counsel was unconstitutional. The Office of the Special Counsel appealed the dismissal to the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals, but it later chose to wind down the case following Trump’s election in November 2024, in part due to its long-standing department policy not to prosecute a sitting president. U.S. Department of Justice special counsel Jack Smith moved to dismiss the case on November 25, 2024, following Trump’s win in the 2024 presidential election.

The Georgia Election Case and State-Level Challenges

Trump was indicted on state charges in an August 2023 indictment in Georgia. Trump faces 8 criminal charges related to alleged attempts to overturn Joe Biden’s victory in Georgia, alongside 18 accused co-conspirators. Trump initially faced 13 criminal charges, 5 of which were dismissed. The Georgia case presented unique challenges for prosecuting a former president at the state level. On December 19, 2024, the Georgia Court of Appeals disqualified Willis from prosecuting the case. The case had been paused while the court decided this issue. As the court did not dismiss the case, another prosecutor could take Willis’s role; however, it will have to be determined whether a state-level prosecutor can prosecute a sitting president (as Trump has been from January 20, 2025, onward) and whether a state-level judge will hear the case.

The Supreme Court’s Game-Changing Immunity Ruling

The constitutional landscape shifted dramatically in 2024 when the Supreme Court weighed in on presidential immunity. Former presidents did not enjoy broad immunity from criminal prosecution until July 1, 2024, when six members of the Supreme Court created that privilege in Trump v. United States. This ruling would have fundamentally changed Nixon’s fate fifty years earlier. The court majority’s ruling that presidents are immune from prosecution for their “official acts” would have absolved most of Nixon’s Watergate crimes. Nixon used the CIA to obstruct the FBI’s Watergate investigation; created an illegal, unconstitutional secret police unit; sicced the IRS on political adversaries; commuted former Teamster president Jimmy Hoffa’s sentence for jury tampering and pension fund fraud in return for union support; and shook down campaign contributors in return for government favors. Under Trump v. United States, Nixon wouldn’t have had to worry about a pardon.

The Constitutional Crisis That Never Was

But what’s most striking today about these arguments is what wasn’t said: that a former president enjoyed any sort of immunity from prosecution for acts committed in office. Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr.’s opinion in the Trump case holds that a former president enjoys total immunity for “official” actions in office and can only be prosecuted for “unofficial” conduct. No such distinction seems even to have occurred to anyone in 1974. In those days, former presidents were not above the law — period. Back then, according to Nixon expert Ken Hughes of the University of Virginia’s Miller Center of Public Affairs, there was no question in the White House, Congress or the Supreme Court that a former president could be prosecuted for crimes committed when he wielded the powers of the presidency. In fact, President Gerald R. Ford conceded as much when he pardoned his former boss. If the law in 1974 were what the court is saying that it is now, Nixon would not have needed a pardon. Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson made this point in the oral argument of the Trump case when she asked Trump’s lawyer, “So what was up with the pardon for President Nixon? I mean, if everybody thought that presidents couldn’t be prosecuted, then what was that about?” (There wasn’t much of an answer.)

From Horse Buggies to Historic Precedents

The journey from Grant’s speeding tickets to Trump’s criminal convictions illustrates how dramatically presidential accountability has evolved—and sometimes devolved—over more than a century. William H. West made a point to show the president—undoubtedly D.C.’s most influential lawmaking citizen—that no one is above the law, no matter the political power they may possess. Somehow, West’s arrest of President Grant was not controversial in its day. In fact, Grant respected West’s decision to arrest him, even saying that he knew he was speeding and deserved to be arrested for it. This year, Americans face a new consequence of the pardon. Because Ford’s decision deprived the country of a precedent for prosecuting a former president, the six Republican-appointed justices on the Supreme Court were able to fill the void with what I see as a radical revision of the Constitution. The contrast couldn’t be starker: a president who accepted responsibility for breaking traffic laws versus decades of legal maneuvering to avoid accountability for far more serious crimes. What started with a simple speeding ticket has evolved into constitutional questions that would have been unimaginable to Officer West and President Grant. Their brief encounter on the streets of Washington D.C. remains the gold standard for how the law should apply equally to all citizens, regardless of the office they hold.